Why Are Bonds Selling Off Again?

Fading optimism about friendlier Fed policy has bond yields heading back to where they started the year.

The bond market is starting off 2023 with a round trip, and unfortunately for investors looking for relief after last year’s brutal losses, it’s now heading in the wrong direction.

To some, the current pullback in the bond market reflects a dose of reality about the pace at which inflation will come down in 2023 and, as a result, how much room the Fed will have for lowering rates by year-end.

“The market was getting ahead of itself,” says Warren Pierson, managing director and co-chief investment officer at Baird Asset Management.

This kind of back-and-forth in the markets could be a dynamic investors should brace for in coming months.

“We are in a very uncertain environment,” says Al Bruno, associate portfolio manager for Morningstar Investment Management. “The volatility in January and February showed that.”

Bond Market Optimism to Start 2023

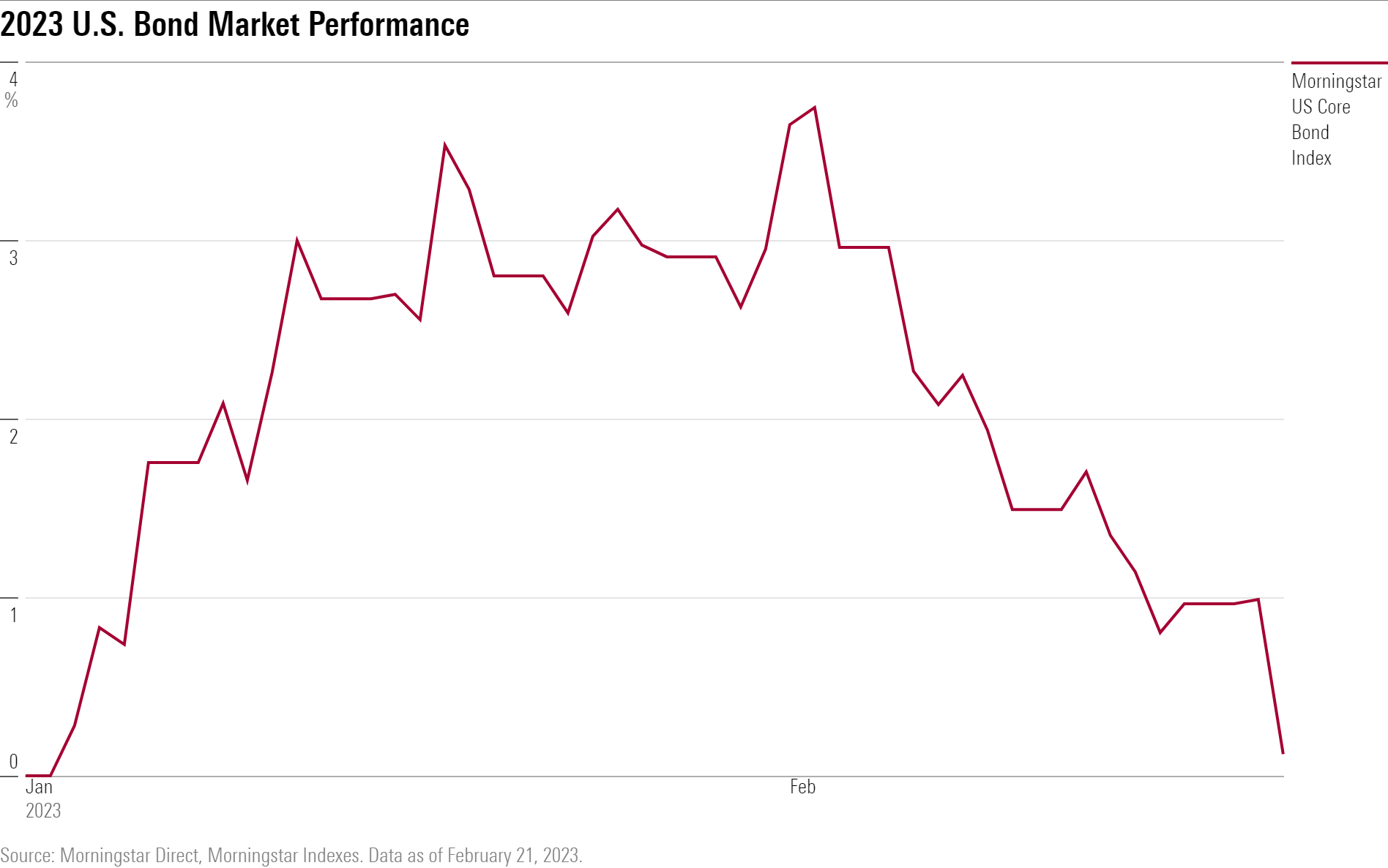

As 2023 got underway, it looked like the light at the end of tunnel was visible for bond investors after the worst year in modern history for fixed-income investments.

There was optimism that inflation had not only peaked last year, but was decelerating rapidly. The Fed, many investors thought, would have only a couple more interest-rate hikes up its sleeve, and then it would be able to start lowering rates by the third quarter.

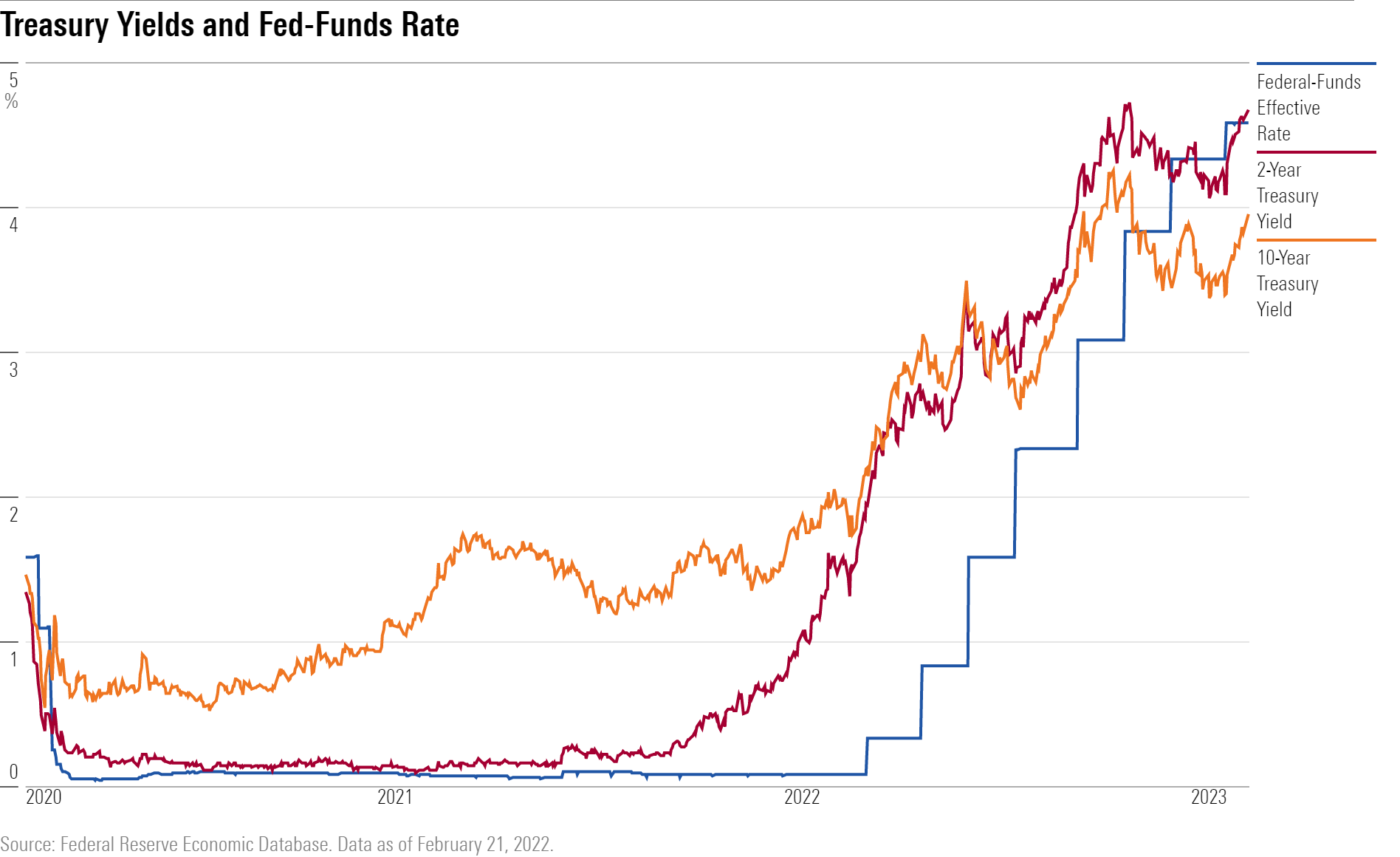

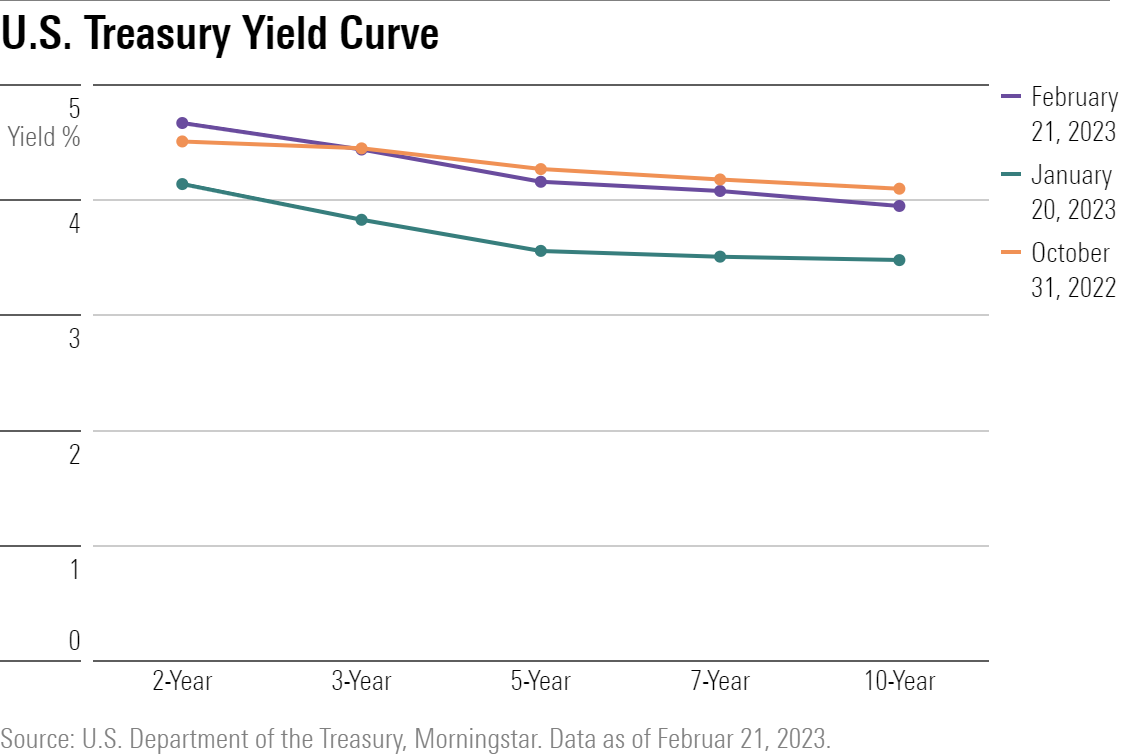

The result was a solid rally to start off 2023. As of Feb. 2, the Morningstar US Core Bond Index had risen 3.7% as the yield on the U.S. Treasury two-year note fell to 4.1% by mid-January from 4.4% at the end of 2022, down from a peak of 4.7% in early November. The yield on the U.S. Treasury 10-year note, meanwhile, slid to 3.4% from 3.9% on Dec. 30 and a November peak of 4.2%.

The drop in bond yields helped propel stock prices higher as well, especially among the kinds of growth stocks that took a beating in 2022 thanks to the rise in interest rates. From the start of the year, the Morningstar US Market Index gained nearly 10% through Feb. 2.

Pierson says the bond rally reflected misplaced optimism about the outlook for Fed policy. “At the end of [2022], the market just didn’t want to take the Fed at its word.”

“The Fed was saying, ‘OK, we’re getting close to the end of raising rates but probably need to go a little more, then hold them up there awhile to beat inflation,’” Pierson says. “But the market was saying, ‘Well, they’re almost done, maybe they raised too far even, and there are high odds of recession at the end of the year.’”

Jobs, CPI Report Derail Bond Rally

Then came the January jobs and Consumer Price Index reports. The January employment report confounded expectations for a slowing economy, showing a significant acceleration in hiring rather than evidence that the United States would soon be heading into a recession.

And in mid-February, the January CPI report—coupled with revisions to 2022 inflation trends—showed that progress in bringing inflation down was moving at a much slower pace than investors had come to believe. Since then, the robust tenor of the jobs report and CPI report has been confirmed by other data as well.

“February has been the complete opposite” of January on the economic data front, notes Bruno. “Job numbers, retail sales, and producer prices were all strong.”

Since then, the bond market has gone into reverse. The Morningstar US Core Bond Index erased all its gains, and as of Wednesday it was essentially flat for the year. The yield on the U.S. Treasury two-year note has risen to 4.7%, and the 10-year note yield has headed back to 4%.

As the bond market has sold off, stocks have retreated as well. Since hitting its Feb. 2 peak, the Morningstar US Market Index is down nearly 5%.

Fed Rate Cuts Now Seen Unlikely in 2023

The principal issue continues to be the outlook for inflation and the Fed’s response. “Data continues to confirm that inflation is a problem,” says Bruno.

The challenge at this stage doesn’t seem to be the trend in inflation—which many observers say is clearly lower—but the pace at which inflation declines.

“We do not think we’re in a new inflationary market that’s going to last indefinitely: demographics and productivity look different now than they did in the 1970s,” says Pierson. “We think the Fed can ultimately get close to its long-term inflationary target of 2%, but it’s going take a lot longer than 2023 to get there.”

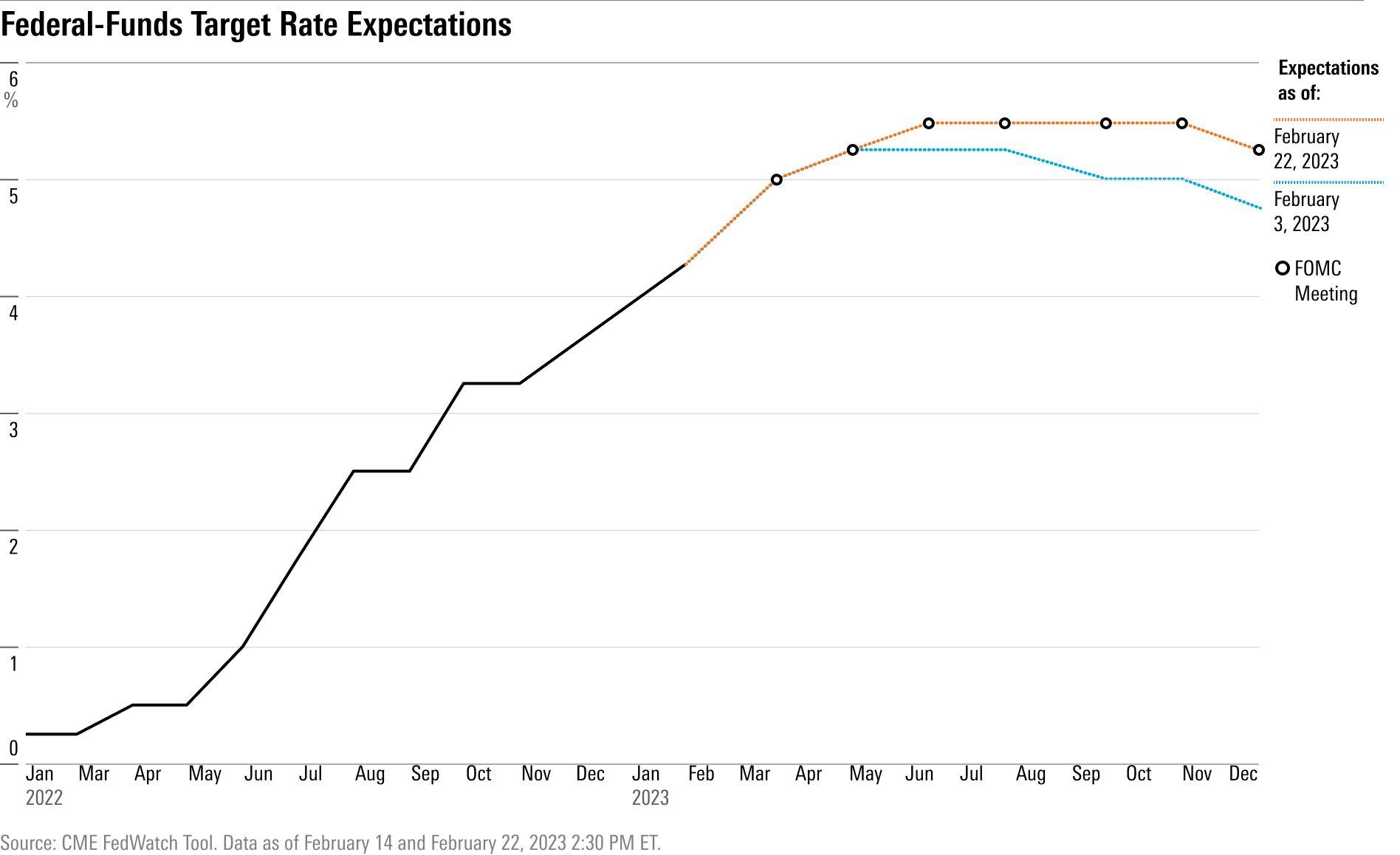

With the idea that inflation is proving stickier than anticipated at the end of last year, the bond market has been reversing expectations for easier monetary policy later this year. The big question is the so-called terminal rate: the level at which the Fed will stop raising rates and pivot to lowering them at some point in the future.

The Fed is now expected to raise the federal-funds rate target to 5.25%-5.5% from its current target of 4.5%-4.75%, hitting that level in June, according to the CME FedWatch Tool. From there the Fed is expected to hold rates steady through the end of 2023.

“The terminal rate keeps getting pushed higher and higher,” says Bruno. “At the beginning of the year, the market was pricing in the Federal Reserve cutting interest rates by the end of the year, now that’s no longer the case.”

“We’ll take the Fed at their word, and we think they are pretty close to reaching their terminal rate of a little over 5%, maybe 5.5%,” says Pierson. “Where there’s disagreement in the market is how long they keep those rates higher.”

Pierson’s view is that the Fed will keep rates higher for longer, “Certainly throughout 2023 and into 2024,” he says. “We are probably not going to see the Fed lowering rates at all in 2023.”

Still, even with that outlook, Pierson doesn’t expect bond yields to go significantly higher, either. For the 10-year note, recently yielding 4%, “we think there’s going be a lot of volatility between 3.5% and 4%,” he says.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ba63f047-a5cf-49a2-aa38-61ba5ba0cc9e.jpg)

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/8b2e267c-9b75-4539-a610-dd2b6ed6064a.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ba63f047-a5cf-49a2-aa38-61ba5ba0cc9e.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/8b2e267c-9b75-4539-a610-dd2b6ed6064a.jpg)