Should International-Equity Funds Own US Stocks?

This tempting option might conflict with investors’ goals.

Editor’s Note: Research and graphics assistance were provided by senior manager research analyst Jack Shannon and associate manager research analyst Tony Thorn.

This past autumn, an international-equity fund manager visiting Morningstar pointed out, with some exasperation, that a rival with better returns had an advantage. His competitor could, and did, invest in Nvidia NVDA and other dominant US companies that this manager couldn’t own, per his firm’s guidelines. In a year when those stocks scored stupendous gains, the playing field seemed uneven.

As it turns out, that rival isn’t an outlier. Many international-equity funds own a handful of US stocks. Some own more than a handful. And a fair number tend to avoid US territory. The issue wouldn’t be worthy of notice if US and international markets provided roughly equal performance or if the mega-caps providing outsize returns were equally distributed among the regions. Neither is the case. With the occasional exception, such as Denmark’s Novo Nordisk NVO, the big, easy-to-find stocks that supercharged last-year’s returns tended to come from the United States.

Of course, having the option to invest in US stocks didn’t guarantee that international-fund managers would choose the right ones. Of the 25 most-heavily weighted US stocks in the MSCI ACWI Index entering 2023, only eight provided headline-grabbing gains, ranging from 49% (Apple AAPL) to 239% (Nvidia). An equal number—eight—posted losses.

The 25 most-heavily weighted foreign stocks in the index also featured plenty of winners, but overall that lineup offered a mixed bag that was less lucrative at the top. Seven of the 25 suffered losses, another six had only single-digit gains, and the group’s biggest winner—Novo Nordisk, riding the enthusiasm for its weight-loss drug—just barely outgained Apple’s 49% rise. None approached the 80% rise of Amazon.com AMZN or the gains of 100% or more posted by Meta META, Tesla TSLA, and Nvidia.

Thus, while US stocks didn’t give international managers a sure path to outperformance, having the option to own a few of the super-performers did bolster their odds of success.

It’s a Growth-Fund Thing

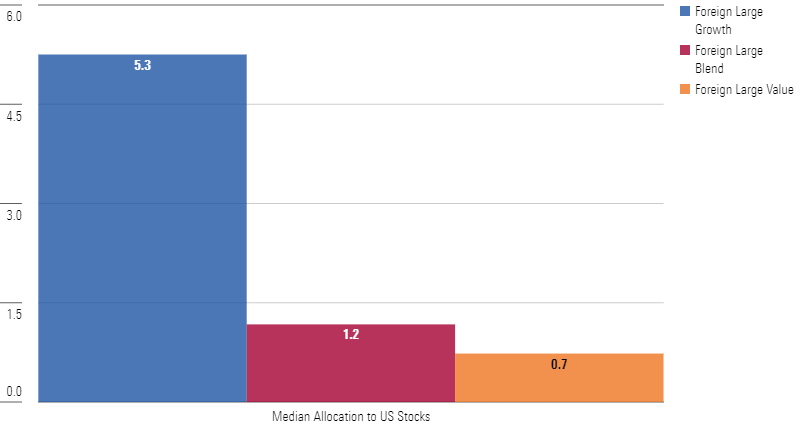

Overall, only a small percentage of international funds invest in the United States. At the end of 2023, the median fund in the foreign large-blend and foreign large-value Morningstar Categories had a mere 1% of assets in US stocks. The figure for the foreign large-growth group was greater but still barely edged above 5%.

Median Category Allocation to US Stocks

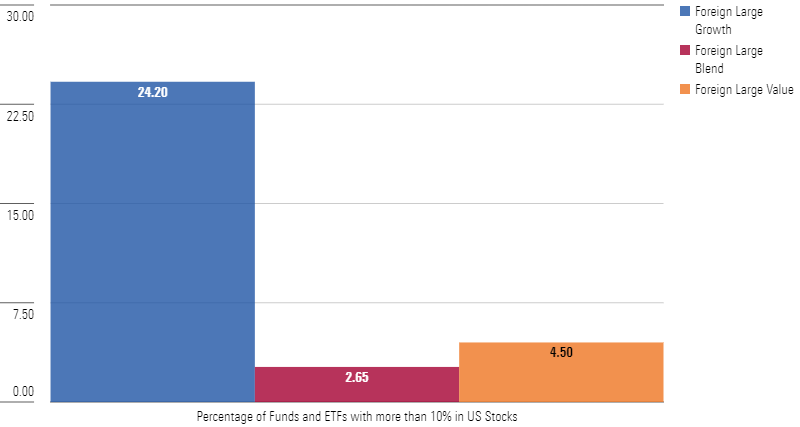

But there’s a more intriguing story under the surface. Many offerings that did indulge did so with gusto. Growth funds took center stage. At year-end 2023, nearly one fourth of the funds in the foreign large-growth category had more than 10% of their assets stashed in US stocks. For the foreign large-value and foreign large-blend categories, the figures were much lower: 4.5% and 2.6%, respectively.

Percentage of Funds and ETFs With More Than 10% in US Stocks

That growth managers would be most eager to venture beyond foreign shores is not surprising; the most alluring US stock choices—the tech giants—lie in growth territory. Many foreign large-growth managers had owned them for years. In fact, in December 2015, the percentage of foreign large-growth funds with double-digit stakes in the US was identical to December 2023′s: 24.2%. Although that number occasionally dipped into the teens in the following years, in December 2021, it was even higher than last year’s figure, at 27.0%. By contrast, in the other foreign large-cap categories, the percentage of funds with double-digit US stakes never reached 10%.

Pros and Cons of US Stock Exposure

The boost they can receive by owning the likes of Nvidia or Meta doesn’t mean all international funds should delve into the US market. In a sense, doing so would defeat their purpose. Many US-based investors have all their other assets invested at home and aim to diversify by adding a fund devoted to foreign markets. It’s the same reason people own other asset classes, such as small caps, bonds, and cash. An international fund with US holdings could give its shareholders even more exposure to stocks they already own, rather than providing the diversification they seek.

On the other hand, as long as it’s allowed by prospectus; isn’t prohibited by informal guidelines or regulatory bodies; and, in the manager’s view, will boost returns for shareholders, it might seem inexcusable not to own a few world-class US companies. Moreover, some managers argue that certain multinational companies, while domiciled in the US, can reasonably be considered international because of the amount of business they do abroad.

Either course is defensible. It’s up to investors to decide which type of international fund they prefer and choose accordingly.

Sour Grapes or Sound Objection?

The complaint of the international-fund manager who trailed rivals enjoying greater freedom might sound peevish. But his point shouldn’t be dismissed. After all, the reason Morningstar created fund categories (and continually updates them) is to ensure that funds are compared with those that share the same investment universe and broad mandate. The goal is to provide performance comparisons that are as fair and useful as possible.

For that reason, we divide international funds into separate categories based on the size of their US stakes. We place funds with US stakes greater than 40% in a Morningstar Category designated as global rather than foreign. And we can exercise discretion: A foreign fund with US stakes consistently bumping up against the 40% threshold gets a hard look.

It would be too cumbersome, though, to establish additional categories with smaller, more-precise cutoffs. All categories have borderline cases and inhabitants that don’t ideally fit the criteria. And some companies that change their formal domicile for tax purposes or other reasons remain, for all practical purposes, as much a US or foreign company as before. Such minutiae would cause endless debates if we tried to establish too many finely grained categories.

Thus, an international fund with no US holdings ends up in a category with funds that own some US stocks. It’s understandable why, in a year such as 2023, that might not seem fair.

However, there’s a workaround. Morningstar tools allow users to create their own subgroups. The aggrieved manager can follow that course to make his case to his clients and superiors. If his fund beat other funds with a similar restriction against owning US stocks and outpaced a relevant benchmark with the same universe, he can state with justification that his fund performed well given the mandate he’d been given.

Not a Unique Case

It’s not unusual for funds to be grouped with others that don’t quite share their approach. For example, in addition to divergent US stakes, international funds can differ markedly in their exposure to emerging markets. When those regions lag, as they have recently, funds that steer clear of them have an advantage over those that invest more broadly. Strategies that invest exclusively in the US can face similar issues. For years, US growth funds with a moderate approach have suffered in relative terms. With less exposure to the popular technology and communications giants, they’ve had an uphill battle competing against bolder funds willing to load up on these highflyers.

None of those approaches is inherently superior. The key is for investors to decide which variety of fund fits their preference. Then, they can investigate data provided by Morningstar, such as location in the Morningstar Style Box and percentage of assets in the US or emerging markets, plus the descriptions and evaluations provided by Morningstar manager research analysts. With that information in hand, investors can find the type of investment that they are looking for.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/657019fe-d1b1-4e25-9043-f21e67d47593.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/FGC25JIKZ5EATCXF265D56SZTE.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-25-2024/t_d30270f760794625a1e74b94c0d352af_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DOXM5RLEKJHX5B6OIEWSUMX6X4.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/657019fe-d1b1-4e25-9043-f21e67d47593.jpg)