10% Stock Weights Are No Longer Shocking for Funds. Should They Be?

More funds are making major commitments to the behemoths.

If a fund manager sinks more than 10% of assets into a single stock, is that a bold move or a conservative stance? The answer may depend on whom you’re asking.

A recent study by Morningstar senior analyst Jack Shannon defined a “big bet” as a holding that not only took up a substantial portion of assets but was also meaningfully overweight versus its benchmark. A 10% stake did not qualify as a big bet if the stock had a 10% weight in the index.

That made sense. For fund managers whose performance is evaluated versus an index, holding a stock at or near benchmark weight—no matter how large the weight—reduces the likelihood of a career-threatening setback. They might consider it a low-risk approach.

Not so for individual investors. Their key aim is not to beat a benchmark, but to accumulate a certain level of savings or income to achieve their personal goals. Viewed through this lens, an unusually large stock position does carry substantial risk even if the size of that stake merely matches the index.

Shannon’s study revealed an increasing number of big bets. A fresh look at the data shows that large absolute weights—defined as 10% of assets or greater—also occur much more frequently than in the past, whether they qualify as big bets or not. And the variety of companies receiving such strong commitments from fund managers has narrowed considerably.

Double-Digit Stakes Abound

Hefty individual-stock positions have become so common in growth-oriented funds that they may not attract much notice. However, the phenomenon stands out to any long-term observer of equity fund portfolios.

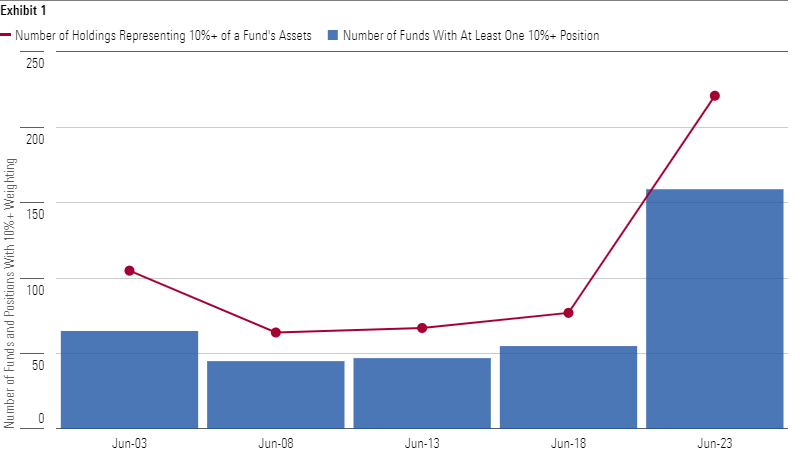

In 2023, 158 of the actively managed, open-end U.S.-equity funds in the nine Morningstar Style Box categories—large growth, small value, and so on—featured at least one holding with a weighting of 10% or more in their portfolio from June 30 or earlier in the year. That amounted to 9.1% of the funds in those categories.[1] There were 221 such positions overall, as some funds had double-digit weightings in more than one stock.[2]

The reason so many funds held large stakes probably lies in the Russell 1000 Growth Index, the benchmark against which most U.S.-focused large-growth offerings are measured. As of June 30, 2023, that index allotted weights of 13.3% and 11.7% to Apple AAPL and Microsoft MSFT, respectively. Managers didn’t even have to overweight them to get to a double-digit stake.

For example, the managers of Goldman Sachs Strategic Growth GSTIX, who aren’t especially bullish or bearish on those stocks, recently assigned essentially market-neutral weightings to them. Yet that approach left the portfolio with 13.6% of assets in Apple and 12.0% in Microsoft. That’s an extraordinary situation from a historical perspective.

It Really is Different This Time

Owning such large stakes might be less noteworthy if it were standard practice. But that’s far from the case. A decade ago only 47 funds (2.3% of the total) had at least 10% of their assets in a single stock—less than one third of the current number.[3] There were only 67 such positions overall. The 2008 numbers were similar. In 2018 the figures remained much lower than today: Only 55 funds (2.8% of the total) had 10% stakes, with a total of 77 such positions.

The Number of Funds With Positions of 10% or More Has Grown Substantially

This trajectory mirrors the explosion in index weights. In June 2013, the Russell 1000 Growth Index did not feature any position above 5%. Five years ago, in mid-2018, the index’s biggest stock, Apple, had “only” 7.1% of assets. Microsoft followed with 5.5%.

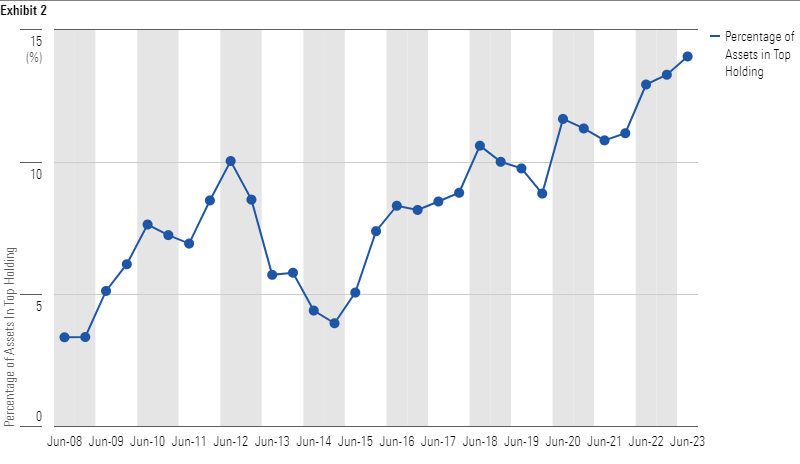

The history of specific funds also illustrates the trend. Goldman Sachs Strategic Growth has not made a habit of stashing 25% of assets in two stocks, as it did this past June. A look at its portfolios from 2008 onward shows that no holding broke the 10% barrier until 2022. At T. Rowe Price Blue Chip Growth TRBCX, Microsoft topped the June 2023 portfolio with a whopping 14.0% of assets, and Apple followed with 11.3%. That too stands out. Looking at portfolios from mid-2008 onward, that fund had a 10% stake in Apple for part of 2012, but then went six years without any stock at that level; only in 2020 did such positions start to appear on a consistent basis. In March 2022, the portfolio contained not just one, but three double-digit holdings.

Weighting of Largest Position in T. Rowe Price Blue Chip Growth

American Century Ultra TWCUX, meanwhile, has long favored Apple. But save for a short time back in 2012, it had no double-digit weights until Apple regained that level in March 2020. That position later soared to 15% of assets.

A Tale of Two Companies

Not all of 2023′s double-digit stakes lie in Apple and Microsoft. A small number of funds make major commitments to companies that aren’t even among the GAMMA heavyweights. (Besides Apple and Microsoft, those include Meta Platforms META, Alphabet GOOG, and Amazon.com AMZN.) But those funds are the outliers. The overwhelming majority of the double-digit weights in 2023 have been in Apple (53) or Microsoft (95). No other company appears more than eight times.

Past lists featured much more variety. Among the 47 funds with double-digit weights 10 years ago, companies from many different sectors were represented. Apple appeared most often, but with a mere six mentions. Alphabet had three. In a telling indication of how drastically the winds can shift, Microsoft did not appear on the 2013 list at all.[4]

Know What You Own

The intent here is not to advise managers to reduce their stakes in the tech behemoths. That’s their call to make. Rather, it’s to warn shareholders that some mainstream funds have much more substantial commitments to one or two companies than they used to.

These stances carry risks. No matter how big, innovative, or dominant, a company—or at least its stock price—can falter. And those funds with heavy stakes in them will feel the pain.

Note: Senior manager-research analyst Jack Shannon and associate manager-research analyst David Carey provided extensive research and graphics assistance for this article.

Footnotes

[1] This study focuses on the Morningstar Style Box categories because while funds dedicated to a specific sector, with a limited investment universe, may be more likely to have large stakes in individual stocks, investors who have chosen such a mandate probably expect that.

[2] The specific number of funds and positions cited may be slightly off owing to missing portfolios or other technicalities. For example, if a fund’s combined weighting of a company’s two share classes is above 10%, it would not be picked up by a screen considering share classes individually. That said, such instances appear to be rare.

[3] The screens identify 10% positions in the fund’s June portfolio or any previous portfolio from that year.

[4] The wide-ranging 2013 list includes many financial firms, including Visa V, Wells Fargo WFC, American Express AXP, Morgan Stanley MS, Bank of America BAC, and MBIA MBI; defense/aerospace firms Northrop Grumman NOC, L3 Technologies (now L3Harris Technologies LHX), and General Dynamics GD; energy giants Exxon Mobil XOM and Shell SHEL; and Berkshire Hathaway BRK.B.

The author or authors own shares in one or more securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/657019fe-d1b1-4e25-9043-f21e67d47593.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/07-25-2024/t_56eea4e8bb7d4b4fab9986001d5da1b6_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BU6RVFENPMQF4EOJ6ONIPW5W5Q.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/657019fe-d1b1-4e25-9043-f21e67d47593.jpg)