5 Charts on General Electric's Fall From Grace

Companies at the top don't stay that way forever.

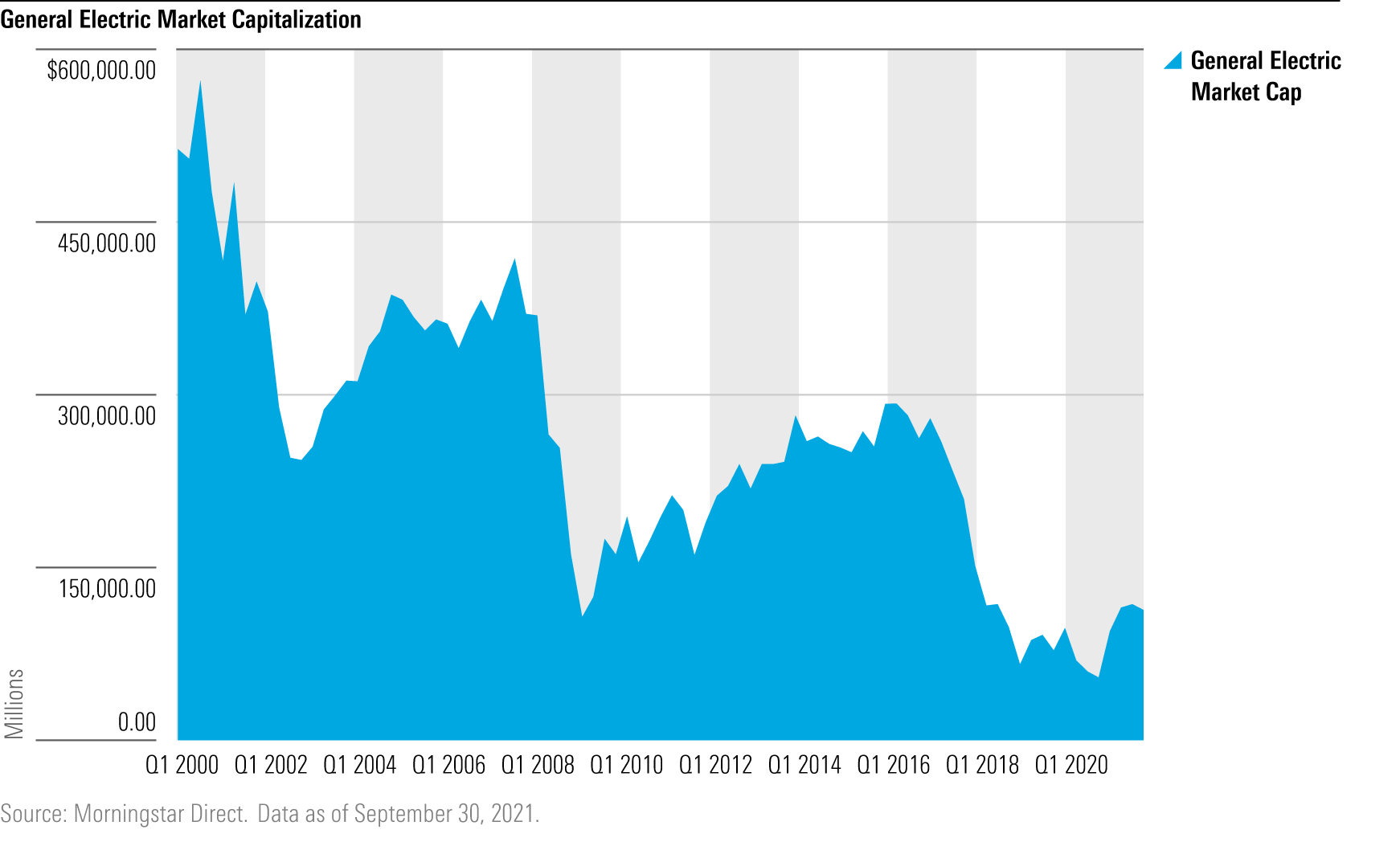

Seasoned investors may have forgotten--and newer investors may find it hard to believe--but two decades ago, General Electric GE was the most valuable company on earth.

That title is now closely fought among technology-driven giants Amazon.com AMZN, Microsoft MSFT, and Apple AAPL. When GE held the crown, it was a sprawling industrial conglomerate with businesses that ranged from credit cards to appliances and jet engines. But in the past 20 years, GE has seen a massive fall from grace. Despite its massive global business presence, it is now the 75th largest company in the U.S. stock market.

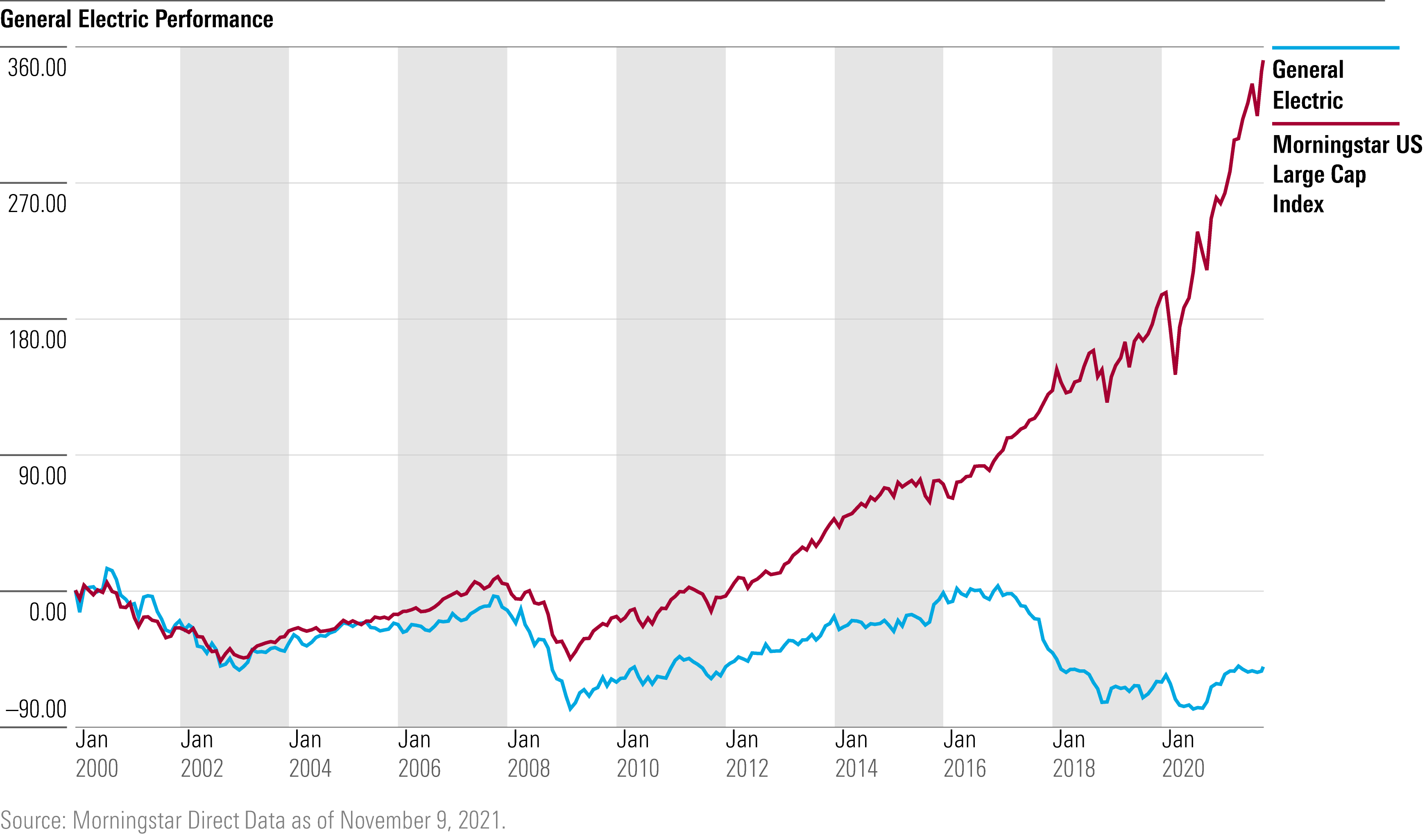

This week, GE announced it is splitting into three companies, a move that Morningstar analyst Josh Aguilar--and the stock market--applauded. GE shares rose 2.4% Tuesday. But since 2000, GE’s stock price has fallen 50%, a time when the Morningstar Large Cap Index returned 350%.

What went wrong for the company over the past 20 years? “A lot,” says Aguilar. "But mostly it was a combination of a deterioration of culture and poor capital allocation decisions.” Now, by splitting into three companies that focus on aviation, healthcare, and energy, “it allows each of its businesses to determine their own destiny and allows investors to pick which combination of GE businesses they like best.”

GE’s tumble from the top is worth tracking. For investors, it’s a clear reminder that times change and businesses that are on top don’t stay that way forever.

As the turn of the century approached, GE was one of the most admired companies on the planet. Before current CEO Larry Culp took over, there were CEOs Jack Welch (1981-2001) and James Immelt (2001-17).

Welch was practically a household name. But despite his broader reputation, “Welch encouraged short-termism and quarterly earnings 'beats' over behavior that helped long-term shareholder value,” Aguilar says. Meanwhile, “Immelt wanted to ignore information that didn’t jibe with his overly optimistic projections, which was particularly dangerous in the M&A context” and which played out in spectacular fashion around GE’s acquisition of Alstom’s power and grid businesses. GE paid $10 billion in the Alstom deal but ended up writing off a $22 billion loss.

Another big hit to GE’s reputation came in the 2008 global financial crisis. Aguilar notes that GE overly relied on its financial unit, GE Capital, to fund GE’s operations, which moved it past its industrial core competency. At one point, GE Capital was greater than 50% of GE’s earnings, and they had lots of underappreciated risks that became visible during the crisis, he says. These included huge liabilities around subprime mortgages, long-term-care insurance, and Polish mortgages denominated in Swiss francs. The financial crisis laid this strategy bare when it lost its AAA rating in 2009, Aguilar notes.

During the financial crisis, GE’s value in the stock market collapsed, falling to just 15% of its peak. While it recovered for a time, that proved to be only a short-lived trend.

GE had a history of poor decisions that stacked on several losses, Aguilar says. In the mid-2000s, the company decided to spin-off insurance assets into Genworth and Swiss Re but chose to retain their insurance liabilities. As a result, GE had to fund over $15 billion over seven years under the supervision of the Kansas Insurance Department. GE also acquired WMC Mortgage in 2004, which went on to declare bankruptcy in 2019, days after GE was fined $1.5 billion from a civic lawsuit about WMC having issued defective subprime mortgages prior to 2008. GE also bought a 62.5% stake in Baker Hughes BKR in 2017 only to lose billions in recent years as GE reduced its stake by more than half. In its third-quarter report, GE reiterated its plans to reduce its stake to below 20%. Baker Hughes fell 22% since the initial deal.

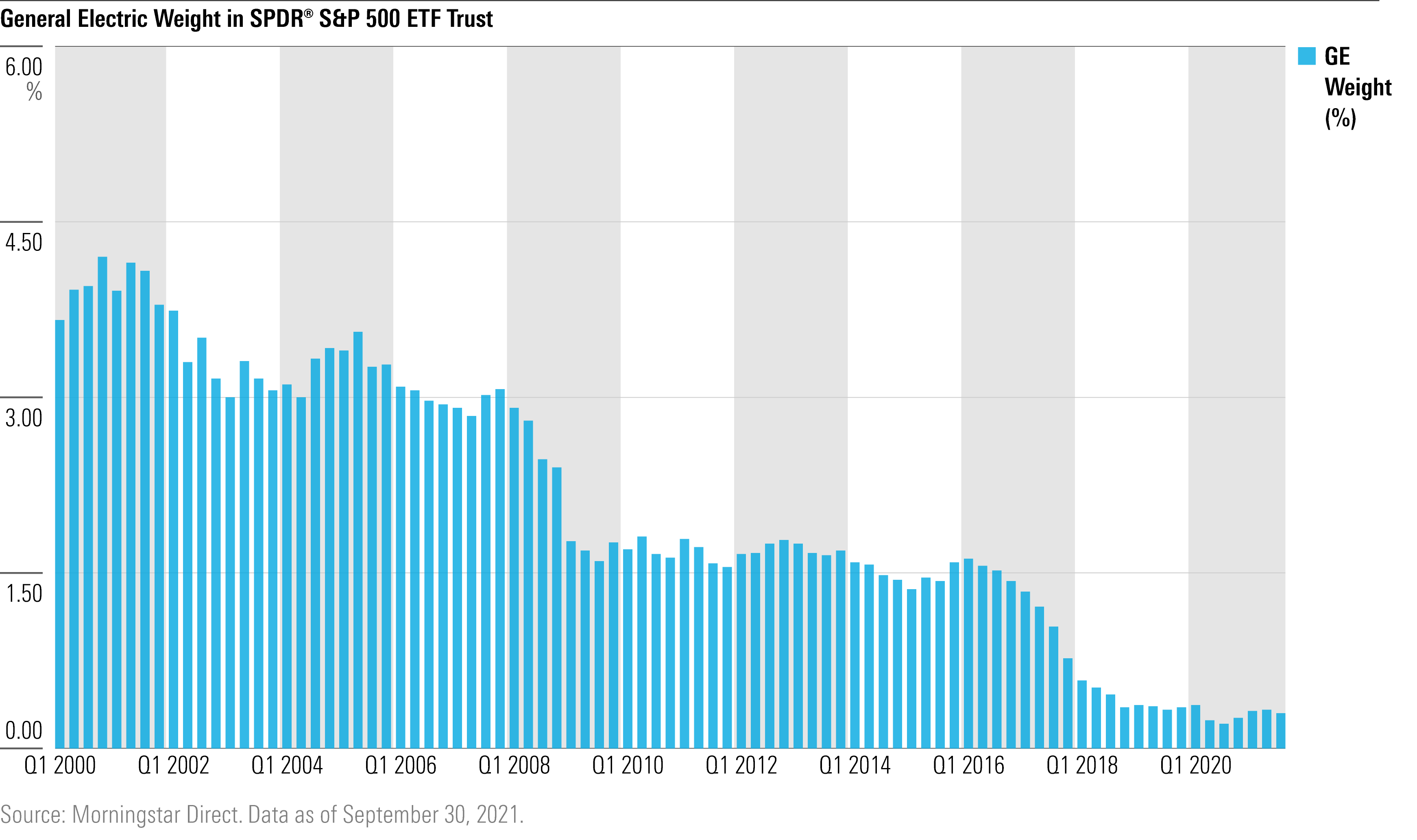

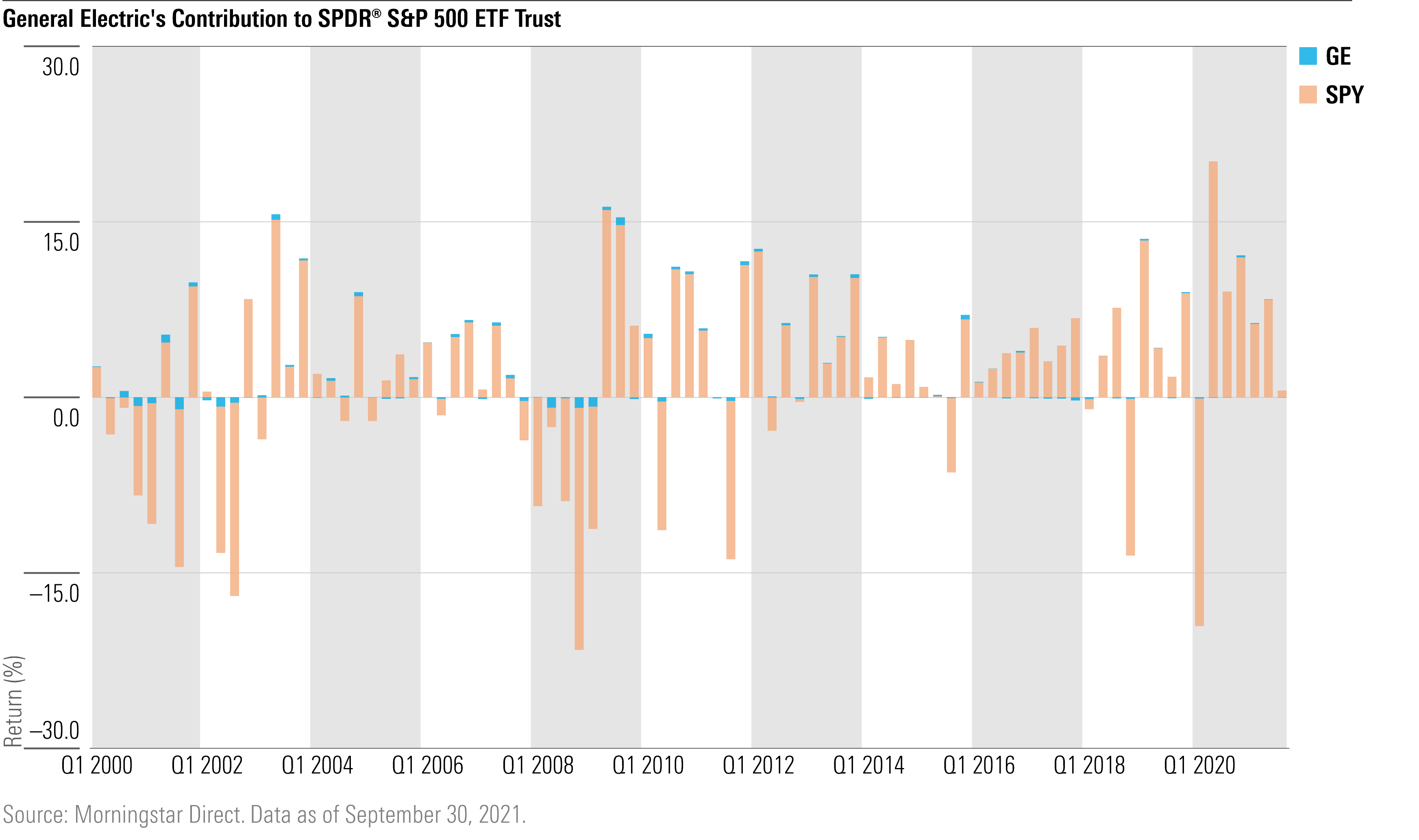

General Electric’s large-cap peers continued to grow and left the former largest company in the world behind. Take GE’s weighting in the SPDR S&P 500 exchange-traded fund: In 2000, GE was the largest holding, comprising as much as 4.2% of the fund. Today, it’s just 0.3%, the 75th largest.

The stock has gone from a market bellwether when it comes to performance to having a nearly nonexistent impact.

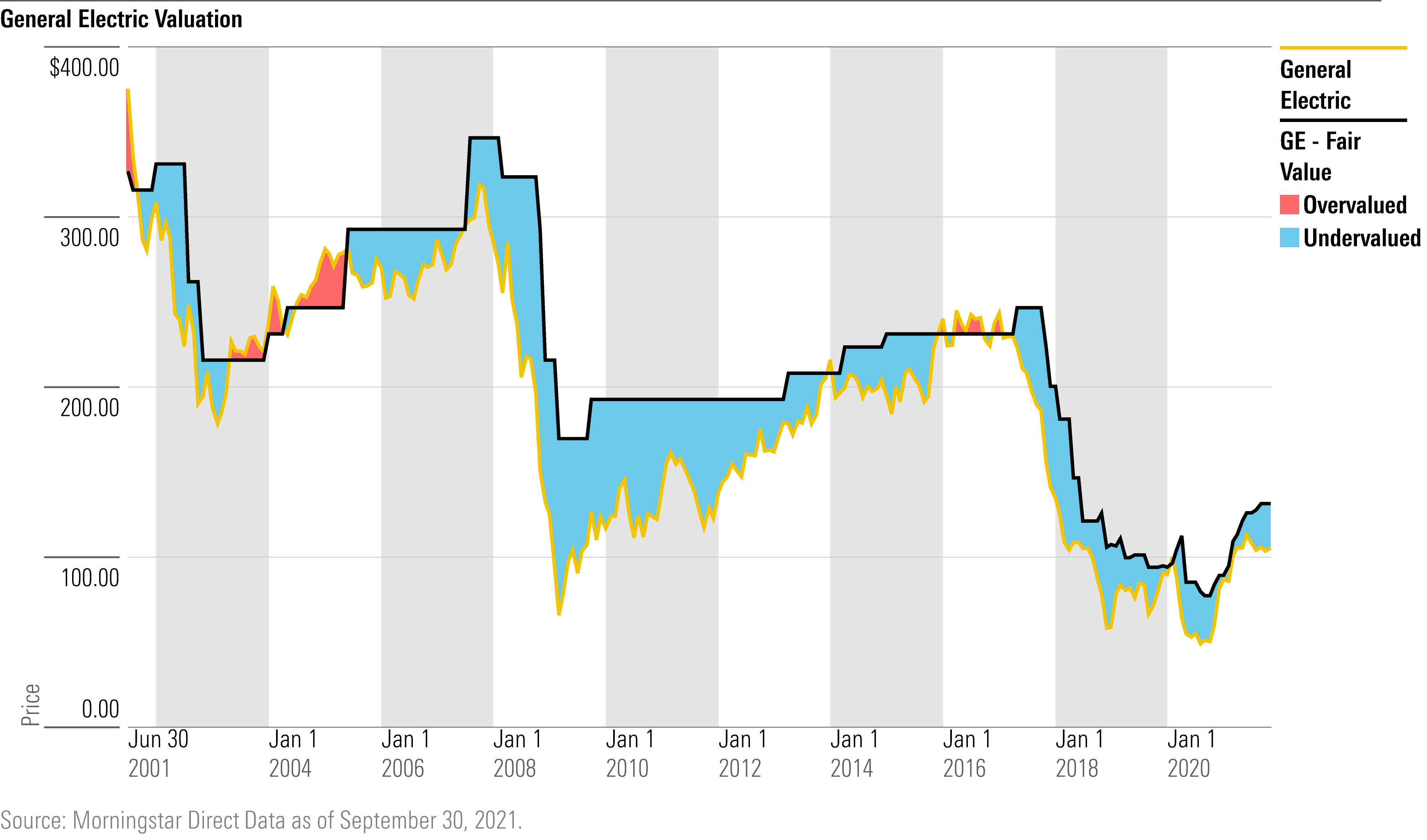

Despite the lackluster performance of the company, Morningstar has long thought General Electric to be undervalued. GE tended to trade 16% below our fair value estimates in the last two decades on average. Today, the company still trades at a 15% discount to its fair value. The recent news that GE plans to spin-off its remaining businesses might be the breath of fresh air it, and its investors, needed, Aguilar says. With each of the three spun-off companies having boards and CEOs, each part of the new General Electric will have dedicated management to spearhead growth.

“We think this news is an important catalyst that will help close the persistent price/value gap for the stock, second only to the company hitting its target of high-single-digit free cash flow margin by 2023, which we think is tantamount to the GE story," Aguilar says. "Nonetheless, investors should cheer the news that management has committed to this target by 2023, as opposed to '2023-plus,' as it had previously communicated. Additionally, investors will now have the opportunity to own either or both exceptional franchises in aviation and healthcare without having to hold on to GE’s more challenged businesses” says Aguilar.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZZNBDLNQHFDQ7GTK5NKTVHJYWA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HE2XT5SV5ZBU5MOM6PPYWRIGP4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/AET2BGC3RFCFRD4YOXDBBVVYS4.jpg)