The C-Suite Gender Pay Gap Persists. It’s Not About Pay Discrimination

It’s about the lack of representation in the highest-paying jobs and industries.

As more women graduated from US colleges in the 1970s, they began to close the pay gap. From the mid-1980s on, women graduates have outnumbered men. But sometime in the 1990s, the gap between male and female college graduates’ earnings stopped narrowing. Today, the ratio of female to male median annual earnings for college graduates is not noticeably different from what it was in 1995.

This is one of the labor market puzzles that Claudia Goldin illuminated in her Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences acceptance speech last fall.

Self-described as a detective of the gender pay gap, Prof. Goldin is an economic historian and labor economist. She was celebrated for her groundbreaking work into why gender-based pay differentials persist to the present—worldwide and in the US—despite major labor market shifts over the last 120 years.

Digging into occupational gender pay differences, Goldin found that the gap is greatest in the business sector—among senior executives, finance professionals, and banking. She coined the term “greedy occupations” to describe job roles that demand more face time, client contact, and networking. These occupations have less flexibility, less predictability, and longer hours.

My own sleuthing, using Morningstar’s Executive Insight dataset with pay data on C-suite executives, underscores Goldin’s findings. For the past several years, I’ve documented the C-suite earnings gap. At the very top of the US’ largest corporations, men continue to be paid more than women.

Roles held by “Named Executive Officers,” or NEOs, whose annual compensation is reported in company proxy statements, are perhaps the “greediest” jobs, as Goldin defines the term.

According to last year’s corporate pay disclosures, women holding the senior-most executive roles in the largest companies in the US earned around 85 cents for every dollar earned by men in these roles. This ratio has ranged between 75% and 88% over the past 10 years.

The 1963 Equal Pay Act makes sex-based wage discrimination illegal. Men and women performing substantially the same jobs in the same place of work must be paid equally.

What Explains the Gender Pay Gap?

Women are paid at least as well for the same work.

Across titles typically held by the highest paid executives at S&P 500 companies, there appears to be no systematic difference in the average earnings of men and women in those roles. At the very top, women CEOs outearned their male counterparts across the S&P 500 in 2022—by an average of $2 million! And women CFOs were paid $1 million more, on average.

Because the number of women in some senior executive categories is very low, one lucrative signing bonus can skew the year’s average. Taken as a whole, however, there does not appear to be a bias against women in pay outcomes across the largest NEO role categories.

At the top of the corporation, there’s a gendered division of labor.

The NEO pay differential arises because women are underrepresented in the highest-paying corporate executive titles.

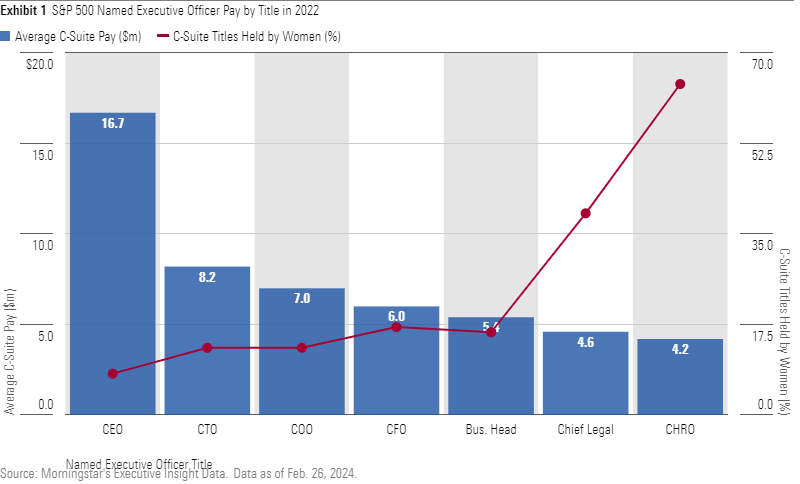

Whereas women held the majority, or 64%, of chief human resources officer titles, this role was the lowest paid among the NEOs of S&P 500 companies in 2022. Women held almost 40% of chief legal officer NEO roles, the second-lowest paid of the major senior executive titles.

In the highest-paid role, women are least represented, holding only 8% of S&P 500 CEO positions. In fact, women are least-represented in all three of the highest-paid C-suite titles.

S&P 500 Named Executive Officer Pay

Women are underrepresented in the highest-paying industries.

Grouping S&P 500 companies into broad industry categories, I compared NEO pay across categories with at least 20 companies. The three groups with the highest average NEO pay are also the industry groups with the lowest NEO representation. Tech companies, financial firms, and companies in the hospitality and entertainment grouping were least likely to have at least one female NEO in 2022. Yet, NEOs in these groups were paid more than $9 million, on average, in 2022. By contrast, 86% and 74% of utilities and industrial companies, respectively, had at least one female NEO. Yet average NEO pay across these groups was well below $6 million.

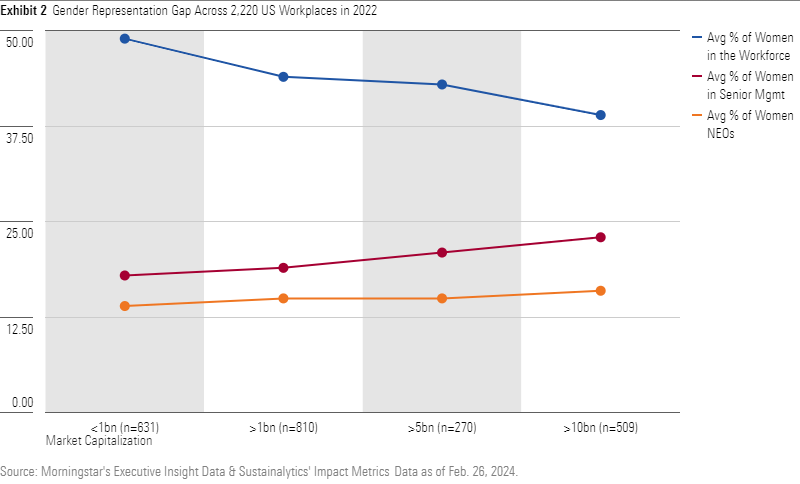

Women are scarcer in large companies and at higher levels of the corporate hierarchy.

Combining Morningstar’s NEO Executive Insight data with Sustainalytics’ impact metrics on women’s workplace and senior management representation for 2,200 US companies, I was able to compare the gender gap at three levels within the corporate hierarchy and across company size. This analysis shows that women become progressively scarcer in companies with higher market capitalizations. While their representation in senior management increases slightly with company size, women’s participation in senior management and C-suite roles, as a percentage of total positions, remains far below their participation in the general workforce, even at the largest, most visible companies.

Impact of Company Size: Gender Gaps Across 2,200 US Companies in 2022

Representation is inching up, but parity is a long way off.

Across the S&P 500′s annual NEO cohort, the number of women has increased 8 percentage points over the last 10 years—to 16.5% in 2022 from 8.4% in 2013. This is going in the right direction, but it’s a rate of change that, projected linearly, only delivers gender parity well after 2060.

Among CEOs, gender parity lies even further out. Even the youngest among today’s working women will likely have a more difficult time reaching the C-suite and the top of the corporation than their same-aged male peers.

Why Does the Representation Gap Matter?

For most, it’s hard to muster outrage at the injustice of someone being paid in the lower-seven-digits versus tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars for a year’s worth of work. But the C-suite gender gap deserves close attention. That is because the progressive underrepresentation of women in higher-paying roles and sectors and more-senior job titles compounds. This magnifies gender-based economic disparities across the entire economy.

According to pay disclosures in companies’ 2023 proxies, $21.5 billion was awarded to the 2,400-odd top-paid workers at S&P 500 companies in 2022. Of this amount, $18.5 billion went to men and $3 billion, or 14%, went to women.

This persistent gender representation gap translates into an unadjusted gender pay gap across society. Pew Research Center analysis shows that, across the US workforce, women earned 82% of what men earned, per hour, in 2022.

What Needs to Change?

Understanding the labor market forces contributing to the gender pay gap can help to inform effective public policies and corporate practices.

Prof. Goldin finds that, for highly qualified workers, female hours in earnings plummet more noticeably with the birth of the first child and women’s earnings relative to men’s decrease across their lives.

She concludes that structural aspects of the labor market are impacted by the distribution of household responsibilities. When faced with the difficulties of balancing demanding jobs and childcare, couples often make career trade-offs that thwart efforts to close the gender gap in high-paying business contexts.

Social policies that support parents can help. But no one policy or intervention is going to erase the multifaceted gender gap.

Still, progress is being made, however modest. Focusing in on pay itself, shareholders have thrown their weight behind greater pay-transparency measures. In 2023, several shareholder resolutions asked companies to report median adjusted and unadjusted gender and racial pay gaps. These were supported by 38% of shareholders, on average. At Nike and Oracle, these two resolutions earned majority support in the second half of 2023.

The gender imbalance at the top of the corporation suggests that compensation structure and the compensation-setting process are driving the gender pay gap. Perhaps a fundamental approach to addressing the gender pay gap in workplaces and society is to stem the inexorable rise in senior executive and CEO pay.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/NNGJ3G4COBBN5NSKSKMWOVYSMA.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6BCTH5O2DVGYHBA4UDPCFNXA7M.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EBTIDAIWWBBUZKXEEGCDYHQFDU.png)