Why I Don’t Own a Home

A firsthand look at the home truths faced by first-time buyers.

Most Americans’ biggest asset, and primary source of wealth, cannot be found in a 401(k) account. Instead, it’s their home. Research done by the Survey of Consumer Finances identified primary residences as the largest asset on household balance sheets.

The United States is not the only property-crazed nation out there. Back in June, my colleague Mark LaMonica wrote a wonderful article about the Australian housing market and why he was opting out. Reading Mark’s article, I was floored by how much of it resonated with me. Like him, I am fortunate enough to have the means to purchase a home. Like him, I have opted not to.

Clearly, I’m going against the grain, and I know it. Only 34% of Americans share my lifestyle; many of them are facing a much different financial picture than I am. And I’m a millennial, which means that I am part of the homeownership-killing generation. I hope that by sharing my personal experience that others may find resonance with it, but of course investing is not one-size-fits-all. Take everything I say with a pinch of salt, ideally sprinkled on top of some avocado toast.

A few facts about me before I begin. I am 28 years old. I live in Chicago. I am married, but I do not have kids. I am fortunate that my personal liabilities are light. My parents paid for my college education, so I graduated debt-free. I do not own a car, but my husband does. Since I do not have children, I’m not anchored to a particular school district.

What’s Your Investment Approach?

In his article, Mark outlined his philosophy for financial success. He organizes his decision-making process around his own personal statement of cash flows, keeping fixed costs at a minimum in order to maximize his flexibility.

Others put housing in an entirely separate bucket from their human capital and treat it as a luxury good to consume. To these homeowners, a house is worth the money they put into it simply because they like the stability a home provides.

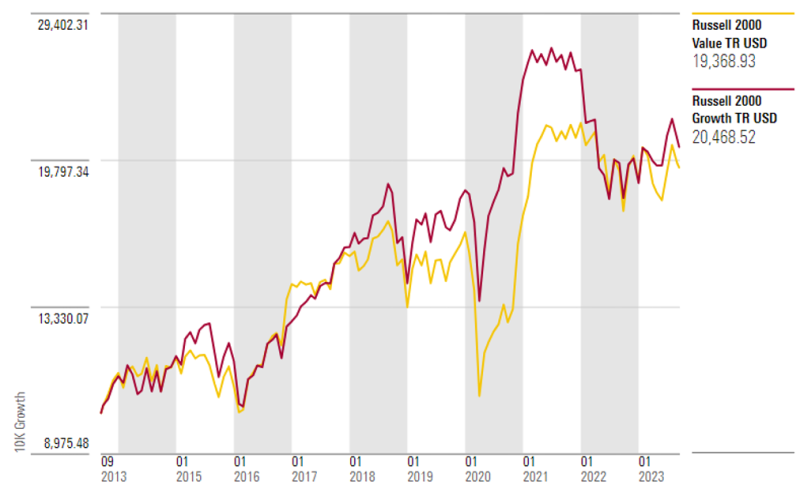

Personally, I can’t stop thinking like an investor, even when I probably should. To make matters worse, I tend to think like a value investor, and value investments can fall out of favor for long periods of time.

Value Investing Can Fall Out of Favor for Long Stretches

Still, I prefer to buy things when they’re cheap. I probably read too much Benjamin Graham at an impressionable age, so now that’s just how I’m wired. You may have a different style, and that’s great. The important thing is to know what it is.

Step 1: Define Your Time Horizon

The stalwart Mark has opted to rent for life. I’m not so resolute—I do happen to be in the position of wanting to own a home some day, if only to taste the freedom of getting to choose a paint color other than “French Gray.” But when is some day? For any investment decision I make, the time horizon is the starting point of my personal flow chart.

Practically, my entry point would be the same as most other urbanites—a starter condo. Let’s say I want to buy a condo at a $500,000 price point, which is slightly below the median price of my area, but I like round numbers. I’ve squirreled enough away for a 20% down payment on that amount, which means I’d borrow $400,000.

Based on a casual survey of my older peers, a starter condo would probably last my husband and me about five years. After that, life starts to get in the way—more dogs, more books, more camping gear, all clamoring for a fixed amount of square footage. Eventually, it becomes time to move on.

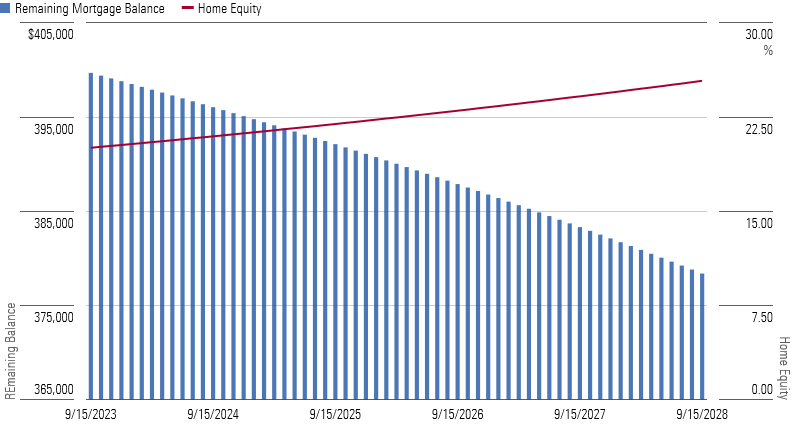

As far as time horizons go, five years is pretty short. The average American spends 13.2 years in their home. Let’s assume I take out a mortgage at an interest rate of 7.6%. Holding home prices constant, by September 2028, I will have notched away an extra 5.3% of equity in my home. (Fear not, we’ll get to return potential in a minute.)

Home Equity Accrues Slowly in Early Stages of Homeownership

Step 2: Identify the Opportunity Set

This is a highly variable analysis based on a lot of factors that are unique to me. With so many levers to pull, people (read: pushy relatives) tend to probe at the boundaries of your investment universe: What if you put more money down, what if you bought somewhere other than Chicago, what if you bought fewer lattes, what if you stayed in the condo for a few more years—if, if, if.

The choices are overwhelming. Know that I’ve run through other scenarios, too. To escape the decision paralysis, today we’re going to just focus on this one investment opportunity. A $500,000 condo within city limits, with 80% leverage and an exit after five years. That’s my opportunity set. It’s probably not yours! Being in the position of even considering a starter condo already makes me wildly fortunate relative to my peers with higher debt burdens. I hope you find this exercise useful anyway.

Step 3: Establish Your Risk Tolerance

The third step on my personal flow chart is to establish my risk tolerance, given my time horizon and opportunity set. I am comfortable taking informed risks over long time horizons, like investing heavily in stocks for retirement while I’m still early in my career. But when it comes to shorter-term investing decisions, I am a nervous Nellie. Tail risks aren’t just theory for me: As a middle schooler during the 2008 financial crisis, I watched as my college savings went up in smoke. I need to have a very high degree of confidence because I know firsthand the pain of starting from scratch.

My threshold becomes even higher when I consider the mechanics of a home purchase from a lending perspective. In investing, leverage is a powerful tool best used sparingly. The statutory limits for a ‘40 Act mutual fund are 33.3% of overall fund assets. That means that for every $1 million in assets under management, a fund can borrow $333,333 to increase its buying capacity.

Meanwhile, everyone considers it normal that homes are purchased with 80% leverage—if not more. For a $1 million home, an investor can borrow $800,000. Yes, the mechanics are very different. But I still think this is kind of wild! For me, it means I need to be extra sure that I’m making the right choice.

Step 4: Conduct a Valuation Assessment

Next, I’m going to tally the expenses, which for homes tend to multiply like rabbits. I’ve tried to highlight the most salient ones, but I don’t think this is an exhaustive list by any means.

- I am probably going to spend at least 1%, or $5,000, a year on maintenance costs. (That expense merely staves off decline; it doesn’t include improvements to increase property value.)

- I’ll fork over another $2,900 in insurance costs.

- I live in a major metro, which means HOA fees will run me somewhere around $4,200 annually.

- I live in Chicago, long an outlier in terms of property taxes. They’re going to set me back $11,000 per year.

- When I sell my property, I’ll probably pay a “back-end load” in the form of closing fees, which are around 8% of the sale price in my area. For the sake of this analysis, I’ll spread that out over five years so that it is $8,000 per year.

Holy smokes. $31,100 is already far more than what I pay in rent each year.

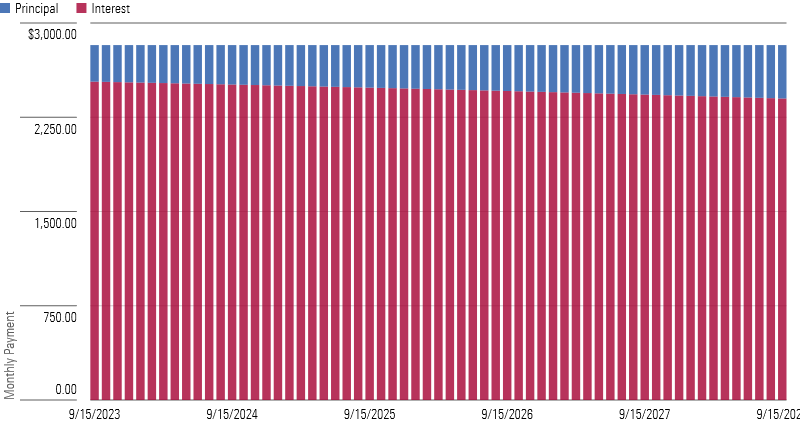

Then there’s the interest expenses. Early on in a mortgage, they’re high. If I sell my condo in five years, I will have made a total of $169,547 in mortgage payments. The portion of those payments that go to interest is $148,300, which leaves a paltry $21,582 for principal payments. First-time buyers in this market—I feel your pain.

In Early Years, Vast Majority of Monthly Payments Go Toward Interest

Interest expenses aren’t all bad, though, because they generate income tax deductions that can be significant. Everybody’s tax situation is unique, but in the 22% tax bracket (2 times the average household income of Chicago), I could deduct $30,300 in interest payments and $10,000 in property taxes from my income. That’s around $40,300 in tax deductions. Adjusting for the standard deduction that’s available to all taxpayers ($27,700), I could save an extra $2,800 a year. That brings my expenses down to $28,300.

If $28,300 was an expense ratio on a mutual fund, it’d be around 5.7% of total net assets. That’s a pretty lousy value proposition when I could just keep my overall costs lower and buy an index fund for free.

However, there’s one final sweetener. Unlike an index fund, residential real estate almost always appreciates in value above and beyond home equity, which is why leverage is so normalized.

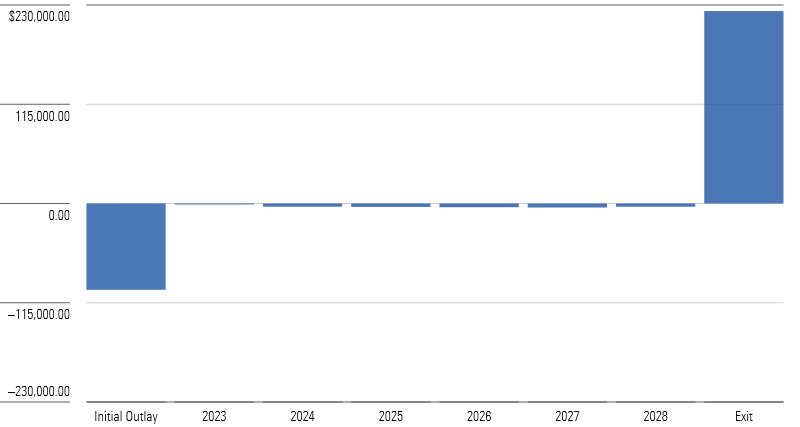

Even though Chicago has been in population decline since the 1950s, it has still seen the value of its properties go up by about 3.8% since the year 2000. (That return goes up to 5.8% if you venture out into greener pastures like San Francisco and Seattle.) If my home appreciates by the usual amount, it would be worth $601,400 by the time I go to sell it. That means that I would earn $222,982 on my total contributions of $121,582 for a 9.9% internal rate of return. Leverage is neat!

Return on Investment Heavily Dependent on Sale Price

That illustration rests on a key assumption, though, one that I don’t hold. I do not assume that the returns that prevailed over the past 23 years are going to hold true over the next five. That’s the real sticking point. If I was going to stay in my home for 10 years, or 13.2, or 30, my calculus would be different. But it’s not.

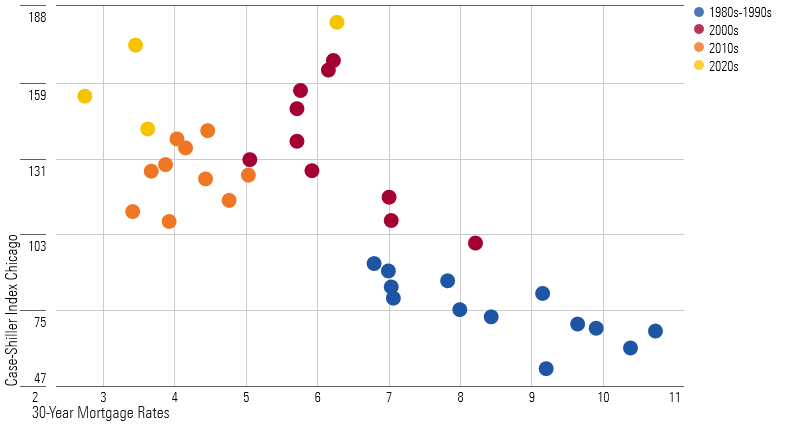

This is the chart that I can’t get out of my head. This is where my internal Benjamin Graham starts whispering in my ear.

2020s Do Not Obey Linear Relationship Between Mortgage Rates and Home Prices

On the y-axis is the Case-Shiller Index for the Chicago Metropolitan Area, which is an aggregation of home price values indexed to the year 2000. On the x-axis, we have the prevailing interest rate, courtesy of the Saint Louis FRED.

When interest rates are low, prices are high. When interest rates rise, prices fall. Either way, the monthly payment that Chicagoans make when they enter into a new mortgage obeys the laws of gravity. Those two big dots, way up high in the chart, taunting Newton? Those are the years 2022 and 2023.

There’s a simple explanation. Home prices are not responding to interest rates as they normally would because buyers are flush with cash and sellers are scarce. That throws the relationship between interest rates and the prices of Chicago home values out of whack. It does not, however, make them any cheaper.

So What?

How the housing affordability question gets resolved remains an open question. Interest rates could come down, making a monthly payment more affordable. Even better for first-time buyers, home prices could go down, making for a cheaper entry point. It need not take a global financial crisis to unwind. New construction could ramp up to meet existing demand, altering the mix of Chicago’s housing stock and increasing affordability overall.

Could it be the case that it doesn’t get resolved at all, and Americans continue to pay ever-higher prices for a place to live? Aussies like Mark would say they sure can. These events are out of my control. What I can control is my peace of mind.

Simply put, for me today, the math ain’t mathing. I have a low degree of confidence that the current return environment for residential real estate in my area will continue to prevail over the next five years, and that makes me unwilling to take a highly leveraged bet on a single asset. I have no qualms about sitting tight and aging out of the starter condo market, at which point the personal economics (not to mention the emotions!) of a home purchase change. I’m a long-term investor, and for the largest asset I will ever own, I don’t mind the idea of being in it for the long haul.

Your math may be entirely different from mine. In fact, I hope it is. Everybody’s investment philosophy is as unique as their fingerprint and formed by their lived experience. I sleep better at night knowing that I have listened to the Benjamin Graham inside my head. You probably don’t have a Benjamin Graham inside your head—lucky you. For something as personal as a home, there’s no right or wrong approach. But there is great power in self-awareness.

Correction (Sept. 20, 2023): In the calculation of income tax deductions, a previous version of this article didn’t account for the tax benefits of the standard deduction.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/eda620e2-f7a7-4aef-bb6c-3fb7f1ac7a38.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MNPB4CP64NCNLA3MTELE3ISLRY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/SIEYCNPDTNDRTJFNF6DJZ32HOI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZHTKX3QAYCHPXKWRA6SEOUGCK4.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/eda620e2-f7a7-4aef-bb6c-3fb7f1ac7a38.jpg)