The Best and Worst Mutual Fund Bets of the Past 25 Years

New research reveals that large single positions rarely make or break portfolio outcomes.

Big bets in mutual funds usually do not pay off.

My recent research documenting 25 years of large bets in mutual funds shows that even successful big bets often don’t make up for index-trailing performance elsewhere in a portfolio. More concerning, oftentimes, the more that managers allocate to a position—and the more bets they place—the worse fund performance gets.

While big bets overall haven’t added value, that doesn’t mean they were all bad. Some, like the Texas Pacific Land TPL and Tesla TSLA bets made by Kinetics Mutual Funds and Baron Funds, respectively, had significantly boosted fund performance as of this writing. Yet lessons from the past suggest caution with these massive stakes.

So which managers made the best and worst bets over the past two-and-a-half decades across the nine U.S. equity Morningstar Style Box categories? The answers are below. Success is measured in two ways:

- Portfolio contribution, which represents how much a given position added to or subtracted from a portfolio’s total return over its entire holding period.

- A value-added approach, which measures the relative impact of a bet by considering how a portfolio would have performed if the bet’s allocation was instead spread pro rata across the remaining portfolio.

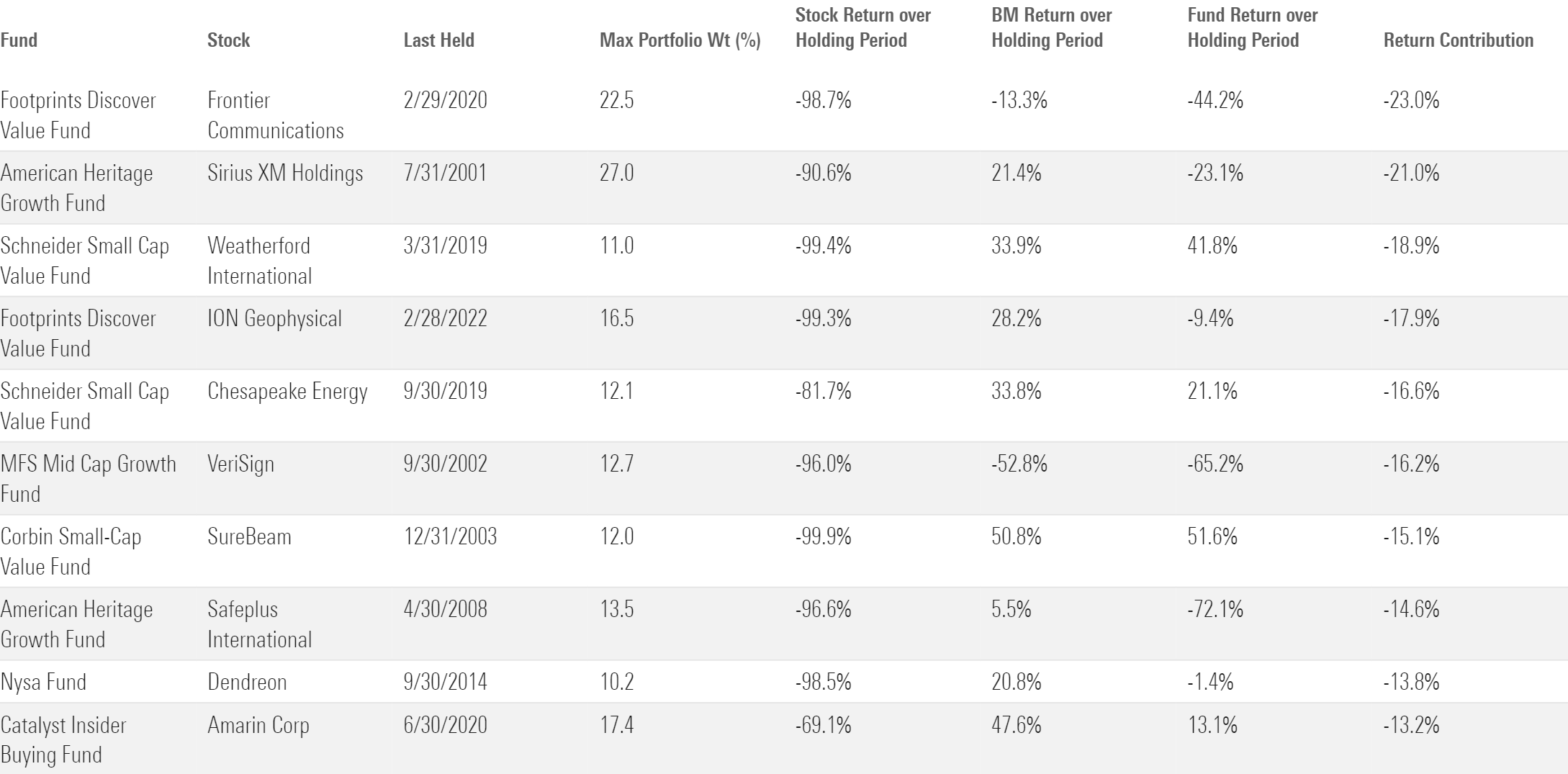

Worst Bets By Portfolio Contribution

Two funds stand out for making particularly bad bets. Footprints Discover Value and Schneider Small Cap Value each made two of the five worst bets of the past 25 years.

Worst Mutual Fund Bets Since 1997 by Portfolio Contribution

They were both burned by bets on distressed energy companies, but Schneider’s double-digit bet on Chesapeake was especially poor; at the time of purchase in late 2015, Chesapeake’s share price had already dropped 85% over the previous 18 months because of depressed oil prices and management turmoil.

Schneider typically employed a deep-value approach, so it frequently bet on turnaround stories. In this case, though, the company’s rebound never came. Chesapeake’s stock dropped an additional 80%-plus and detracted 17 percentage points from performance over the stock’s holding period. The fund’s 21% return widely lagged the Morningstar US Small Cap Broad Growth Index’s 34% gain and proved a costly mistake. If it had never owned the stock, the portfolio would’ve gained around 42%, comfortably more than the index. Schneider Small Cap Value was never a big fund; it held around $25 million in assets when it first bought Chesapeake. But its missteps led investors to lose confidence and consistently withdraw money starting in 2017. The Chesapeake position was sold in 2019′s fourth quarter, and by 2020′s third quarter, the fund itself was liquidated, sent to its grave by two horrible bets on energy companies.

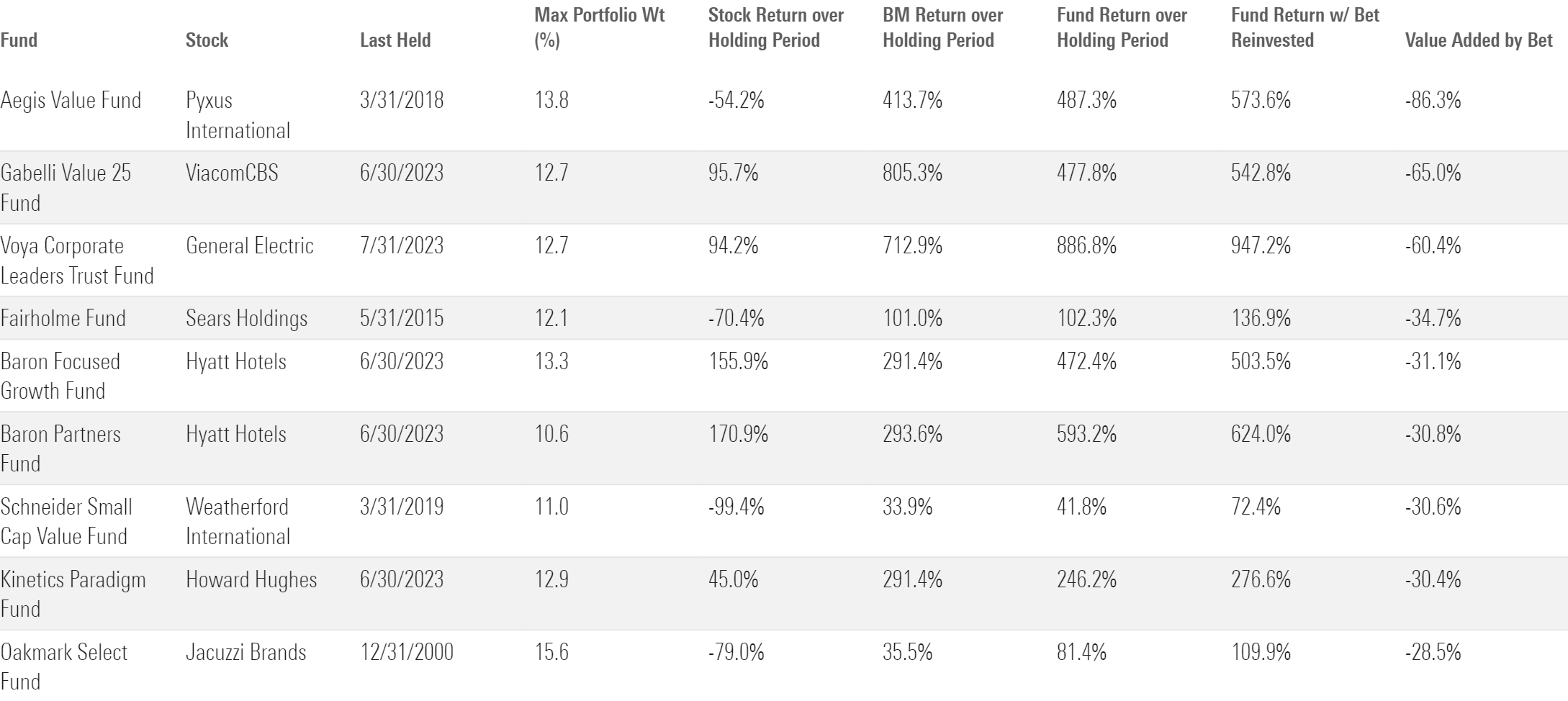

Worst Bets by Relative Value Added

Bad big bets were not always due to companies imploding. A manager who bets big on a stock that appreciates, but at a significantly lower rate than the fund’s index, has made a bad bet in relative terms, even if it boosts portfolio returns in an absolute sense.

In fact, few big bets were bad in an absolute sense, and only about a fourth of bets identified in my research ever lost value over their total holding periods. Of the 10 absolute worst bets by contribution in Exhibit 1, only one made the list of the 10 worst relative bets in Exhibit 2, highlighting that the bulk of foregone returns comes from betting on ho-hum, lagging stocks rather than those that completely blow up.

Worst Mutual Fund Bets Since 1997 by Value Added

Take Baron’s stake in Hyatt Hotels H, for example. In both Baron Partners BPTRX and Baron Focused Growth BFGFX, the stock has commanded upward of 10% of portfolio assets at times. Over both holding periods, the stock more than doubled. Yet, in relative terms, it was not a good bet. Hyatt gained 156% when Baron Focused Growth owned it while the Morningstar US Large-Mid Cap Broad Growth Index appreciated 291%. Both funds would have been better off if the Hyatt position was reallocated to the rest of the portfolio, though their huge (and to-date, successful) bet on Tesla means that almost any holding looks like a relative detractor if removed and reallocated across the Tesla-heavy portfolios.

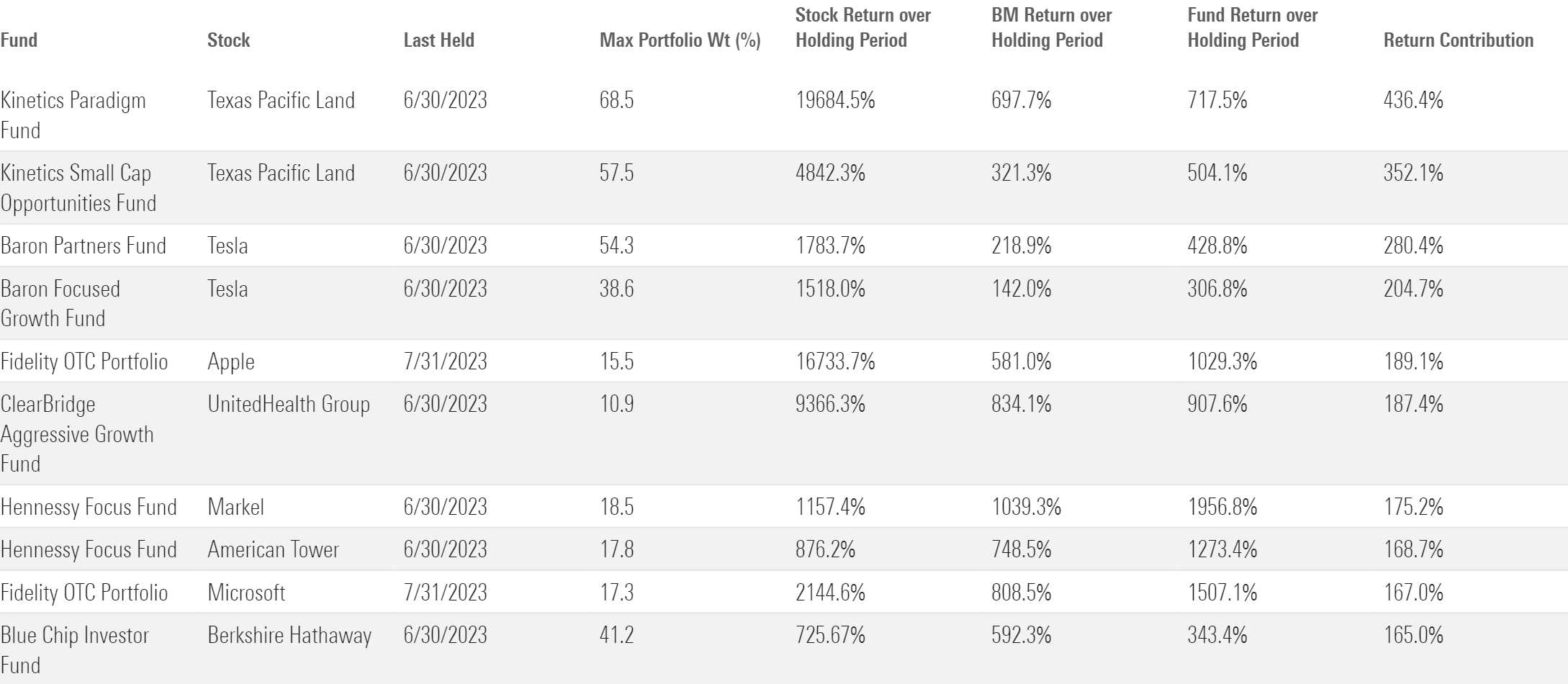

Best Bets by Portfolio Contribution

Baron’s Tesla positions are some of the best big bets ever made. Tesla alone is responsible for roughly two thirds of the returns of each of those Baron portfolios. Only Kinetics’ massive but controversial bet on Texas Pacific Land trumps it. Like Tesla for the Baron funds, Texas Pacific Land alone generated 60% to 70% of the returns posted by Kinetics Paradigm KNPYX and Kinetics Small Cap Opportunities KSCYX.

Best Mutual Fund Bets Since 1997 by Portfolio Contribution

Fidelity OTC FOCPX, one of the top-performing funds in the large-growth Morningstar Category over the past 10 years, has benefited tremendously from longtime sizable positions in Apple AAPL and Microsoft MSFT, two of the category index’s most successful stocks. Its status as a nondiversified fund has allowed it to stake a fourth of its assets in those two stocks, a benefit over diversified peers, which can’t do the same. Just six of the category’s actively managed peers had bigger stakes in those two companies as of their latest portfolios in August 2023.

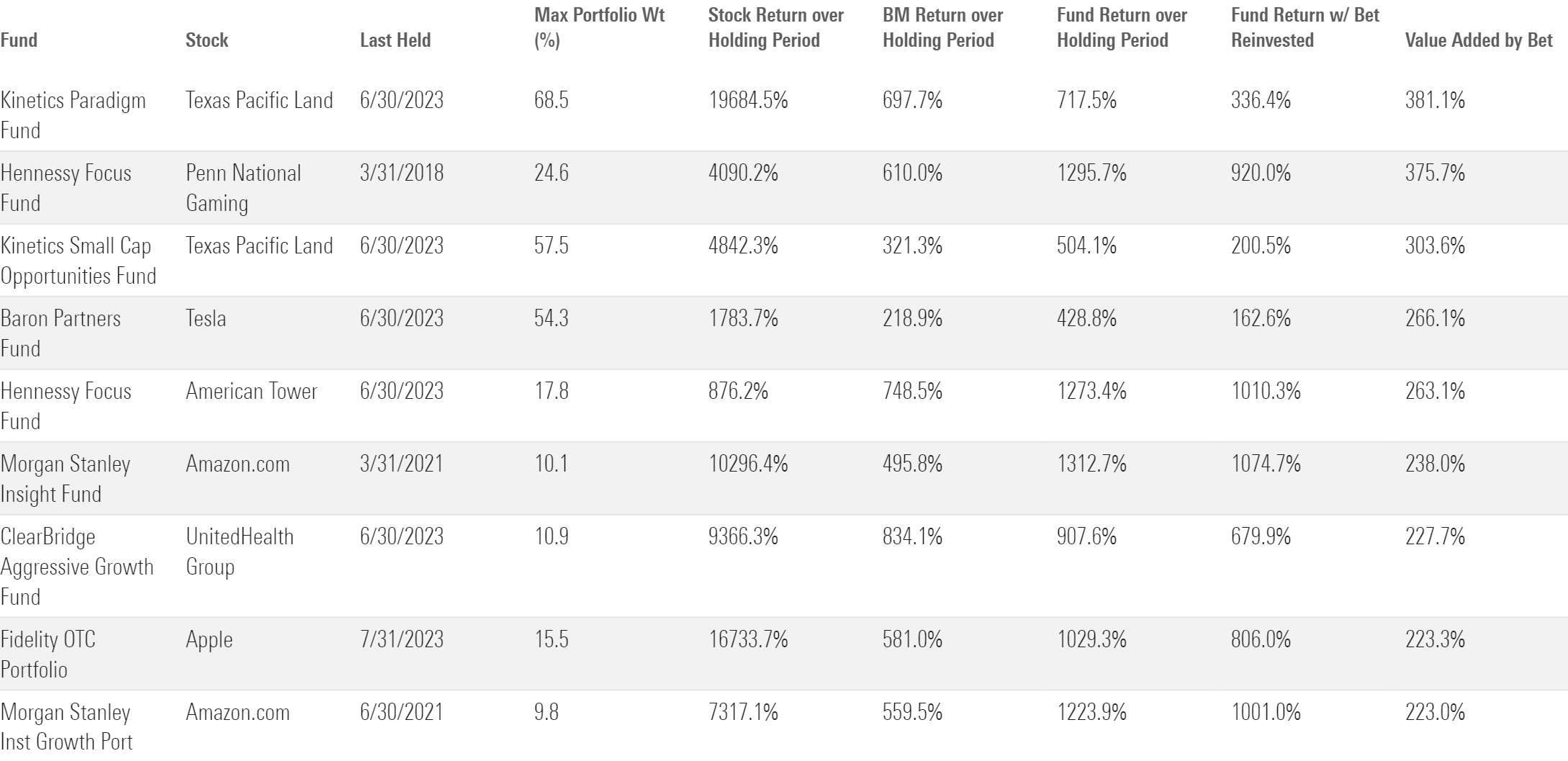

Best Bets by Relative Value Added

From a value-added perspective, the Texas Pacific Land and Tesla stakes for Kinetics and Baron, respectively, look even better. In both cases, the managers clearly bet on the right stocks, as the rest of their portfolios significantly lagged their category’s Morningstar index. Of course, if managers Murray Stahl of Kinetics and Ron Baron of Baron Partners didn’t own those stocks, their portfolios likely would not have been simple prorated reallocations of the remaining holdings. While their bold calls have paid off, investors should consider what might happen if those companies flounder and whether the managers can find other index-beating stocks to keep their funds afloat.

Best Mutual Fund Bets Since 1997 by Value Added

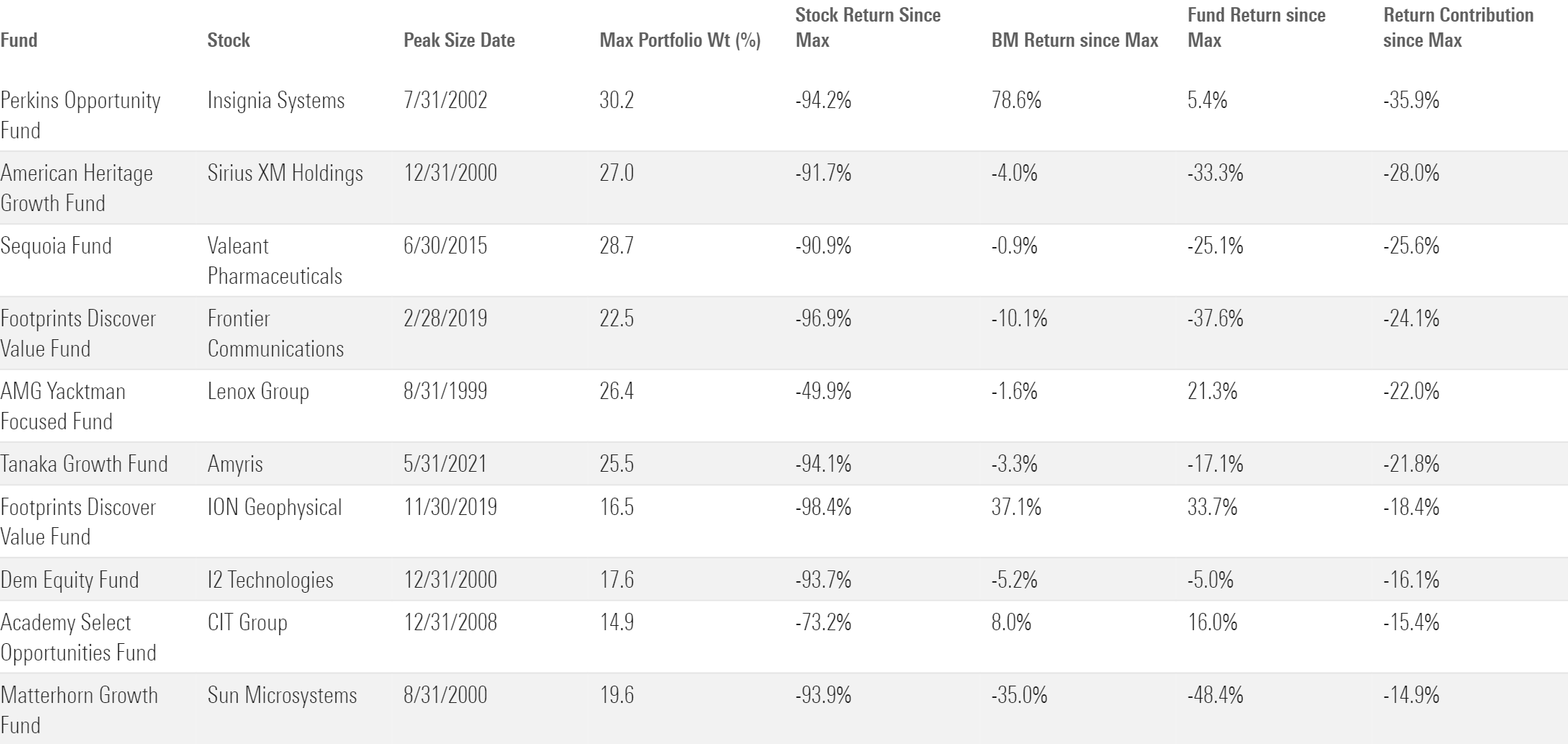

Worst Bets Following Peak Position Size

Despite some big bets’ successes, investors buy shares of mutual funds throughout a stock holding’s life span and may not reap all the rewards. Positions are the most dangerous when they reach their peak levels, as they often arrive there through price appreciation rather than share accumulation, meaning that peak position sizes often coincide with peak valuations for a given company. Half of the bets in the study lost value in an absolute sense after reaching their largest allocation. These were not small declines, either. A fourth of bets lost 25% or more following peak size. This speaks poorly to managers’ abilities to sense elevated valuations and trim top positions that may not be as well positioned for the future. Exhibit 5 shows the 10 worst bets by portfolio contribution following a position’s maximum allocation.

Worst Mutual Fund Bets Since 1997 From Maximum Position Size Through Position Liquidation

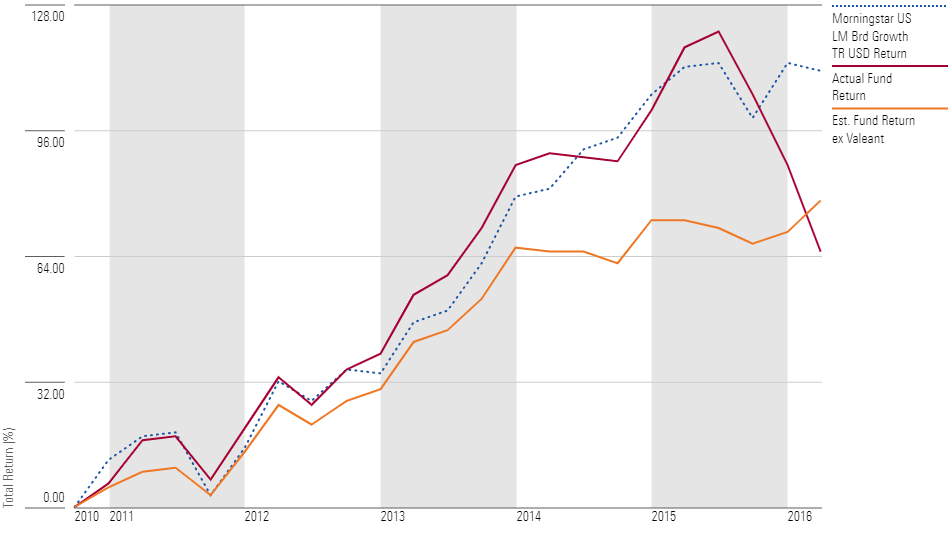

Sequoia Fund SEQUX learned this lesson the hard way through its infamous bet on Valeant Pharmaceuticals. Sequoia’s massive loss on the position was mostly the evaporation of paper profits. From an accounting point of view, the loss on the position was essentially what Sequoia initially paid, about $250 million. But it was a horrible bet for fundholders who bought shares when it reached its peak, around June 2015, as the managers let the position balloon while not taking any gains. The fund’s position in the stock lost about $2 billion of its value between July 2015 and March 2016 as Valeant was probed by Congress over pricing practices and the closure of an affiliated pharmacy. If it is any solace for investors, they would not have fared much better without the bet. The rest of the portfolio greatly lagged the benchmark, too, as shown in Exhibit 6.

Sequoia’s Returns With and Without Valeant Pharmaceuticals

Are Big Bets Worth It?

For most managers, no. While there have been some instances where massive bets have paid off, the majority of large portfolio bets do not swing portfolio outcomes.

Our research paper documents over 2,400 portfolio bets made since 1997. Over the bets’ holding periods, just 37% of their funds topped their Morningstar indexes. Of the index-beating funds, 77% would have still topped the benchmark if the bet was never placed and its stake reallocated among the remaining portfolio. Of the 63% of bets whose funds did not top their Morningstar indexes, just 2% of those would have beaten their benchmark if not for the bet.

Ultimately, strong stock-picking throughout a portfolio is what drives excess returns, and large single positions rarely deserve all the credit or all the blame for a fund’s performance.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/b0c51583-b9a2-49eb-9a8f-5f25a8bda4a3.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/5WSHPTEQ6BADZPVPXVVDYIKL5M.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BNHBFLSEHBBGBEEQAWGAG6FHLQ.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/b0c51583-b9a2-49eb-9a8f-5f25a8bda4a3.jpg)