Are Funds Making Private Investments Really ‘Volatility Laundering’?

Some return smoothing could actually be healthy, but there’s more to it.

Mutual fund managers, envious of the massive inflows enjoyed by private equity and interval funds, have recently added a new term to the financial lexicon: “volatility laundering.”

Volatility laundering is a somewhat derisive term that picks on funds that buy private investments. The thinking goes that they don’t actually have lower risk than funds that trade in public investments—they simply force investors to ignore that volatility by hiding it from them.

This happens in a few different ways. Private-market money managers typically price their holdings quarterly, which results in fewer observations and smoother returns relative to an investment that trades daily. Private funds lock investors’ money up, either through capital calls or gating, which prevents investors from withdrawing their money. Unlike a mutual fund or an exchange-traded fund, private funds don’t allow investors to check their performance in between pricing cycles, which means that when investors do get word of their performance it’s delivered in context.

Although these conditions all sound restrictive compared with the freewheeling autonomy of a brokerage account, I’m inclined to think that these tools can be used to our benefit. Like ostriches, we humans know deep in our hearts that we are sometimes better off burying our heads in the sand if it keeps our worst impulses in check. (See: “Ignorance is bliss,” “what you don’t know can’t hurt you,” or my personal favorite when cleaning my apartment, “out of sight, out of mind.”)

Long-term investment strategies are often more successful when investors resist the temptation to react to every market movement. But it can be difficult, bordering on impossible, to ignore bad news when that information is just a click away. Could it be that a certain amount of self-imposed “volatility laundering,” which is really just return smoothing, is actually healthy?

Of course, there’s more to it than that. Its detractors make three key arguments against return smoothing that I think require a rebuttal in order to reinforce why it’s not as much of a problem as some claim.

Risky Business

The chief argument against return smoothing is that it doesn’t just mask the true level of risk an investor faces, it understates it.

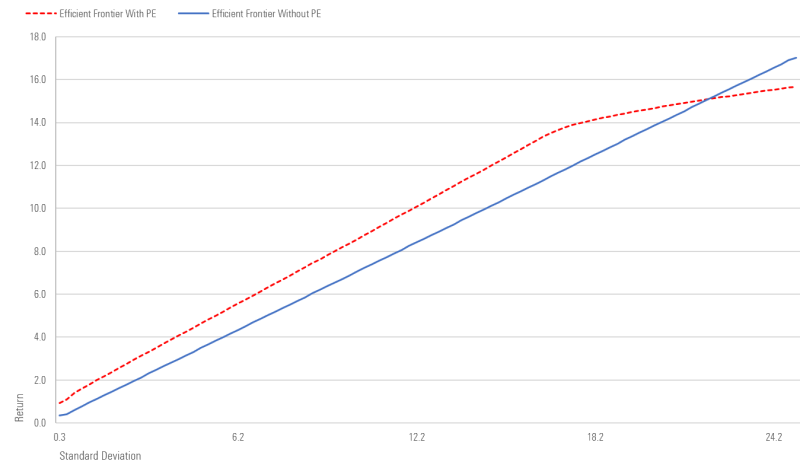

Private markets do indeed exhibit lower standard deviations than perhaps they should, which does wonky things to models that require quantitative inputs. If you’ve ever tried plugging the return characteristics of private equity into an efficient frontier, you know what I mean.

Private Equity Reshapes Efficient Frontier

But here I would draw a distinction between risks that are observable and those that are not. Yes, private markets do carry fewer observable risks. But in exchange for that, investors have to absorb a host of other risks to manage, including cash flow management, leverage, and rebalancing.

Are those risks understated? I’m not so sure. Private markets are restricted to accredited investors for a reason. Lots of due diligence must be performed before a potential investor even gets in the room with a private manager.

If anything, I think we might understate the risks we court in our everyday lives outside of private markets.

Let’s focus on leverage for a second. People take big swings with leverage all the time; they’ve become so normalized, I don’t think we realize how bonkers they are. Take real estate, for example: Homes are typically purchased with a 20% down payment, and everyone accepts that as the industry standard. But from a financial perspective, that down payment means that the investor is leveraged up 5 times on their investment, which should make any investment manager blush. For reference, most long-short equity funds only take on 1.4 or 1.5 times leverage—and unlike a long-short fund, a house is a single asset!

Return of Principle

Another argument centers around a hypothetical scenario, wherein private funds can use return smoothing and upbeat valuations to shield investors from realizing the true extent of their losses until it’s too late. If that investment is subsequently liquidated in a hurry, it may be worth less than valuations promised.

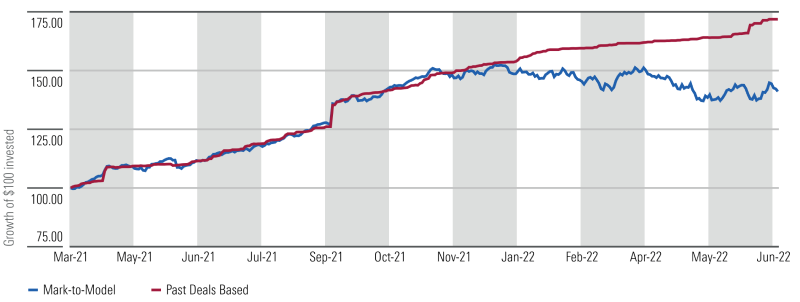

Mutual fund managers are broadly correct that private-market companies and their debt are not innately less risky than their public-market peers. If they were repriced as frequently, our research shows that they’d follow a similar trajectory to their public-market peers.

Morningstar Research Shows That Private Investments Would Decline if Re-Priced Outside of Valuation Rounds

The flexibility afforded to private managers on valuation makes the option to fudge the numbers on a drawdown a very real possibility; there are certainly one-off events where this will be the case. But these bait-and-switch cases aren’t limited to private funds. And I’m inclined to believe this fear stems in part from availability bias, which clouds judgment by overestimating the probability of rare events.

Consider the alternative. Jumping in too late and selling out too early are both more-frequent investment mistakes than buying and holding for too long. Morningstar research shows that on average investors lose about 1.2% a year in the equity markets from mistiming trades. Errors of commission can be even more harmful than errors of omission.

Multi-Asset, Multiple Facets

An undeniable concern associated with private investment is the potential disruption it may cause to portfolio allocations. Investors flocking to the asset class because of its return-smoothing characteristics may unintentionally bite off more than they can chew.

The rate of capital commitments for a private investment is unknowable ahead of time. Overeager investors may inadvertently commit too much capital and be forced to watch helplessly as they become overallocated to private investments relative to their desired asset allocation. The shares in private investments are illiquid, so it may be impossible to rebalance back to desired levels.

This argument holds the most water for me. I’ve seen it happen before. However, it’s also the least salient.

More-frequent repricing is not the solution to this problem, because the core issue is not that private-market investments are too tempting for investors to resist. The issue is that some investors fail to model their risks appropriately. That can happen in any asset class, no matter how alluring.

Reinventing the Wheel?

At the Morningstar Investment Conference back in April, our CEO Kunal Kapoor talked about the barriers he faced to investing in his first mutual fund. He had to write a check, take it down to a bank’s brick-and-mortar location, and request to open an account.

Since then, investing has evolved. Young guns can set up an account in minutes from their cellphones. The advent of technology and instantaneous access to portfolio information through online platforms like Morningstar is undeniably a good thing. It puts more information in the hands of investors. Holding fund managers to account for their performance has never been faster or easier.

In some ways, though, it seems like we keep reinventing the wheel. We keep finding ways to turn ourselves into zombies, whether that’s by pouring most of our net worth into a home that we can’t value until we sell or by setting up a 401(k) account and throwing away the password.

Return smoothing is no different, and no more worthy of scorn. Investors in private equity are exchanging daily volatility for other worries; that’s a fair trade. It’s a way to impose investment discipline and emotional regulation on people who are self-aware enough to know that they can’t do it by themselves. True, that alone may not be worth 2% of AUM, but it’s certainly a service nonetheless. I see no reason to deride it. Ostrich away.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/eda620e2-f7a7-4aef-bb6c-3fb7f1ac7a38.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/CGEMAKSOGVCKBCSH32YM7X5FWI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BL6WGG72URAJJJCPC4376SZKX4.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/eda620e2-f7a7-4aef-bb6c-3fb7f1ac7a38.jpg)