A Matter of Faith

Faith-based investing is a key chapter in the sustainable-investing story.

The Orlando World Center Marriott isn’t a natural home to a burgeoning investing movement. Canned music plays in the elevators, and vacationers amble through the lobby en route to Epcot. But behind a closed ballroom door a few feet away, all eyes are on the band. The vibe is a prayer meeting/concert. And the attendants—more than 2,000 of them—are swaying to the music, many with palms held aloft and eyes closed in ecstasy. These are the faithful, led by the disciple Timothy’s instructions to “be rich in good works, to be generous and ready to share.” Most attendees are financial advisors, as content in the realm of the secular as the divine.

Welcome to the annual conference of Kingdom Advisors, a rapidly expanding association of advisors that aims “to carry biblical financial wisdom to their clients, peers, and community.” Today’s rocky markets pose a challenge for advisors. Many Kingdom advisors hope that a new kind of conversion—the conversion of conventional portfolios to so-called biblically managed portfolios—will help them retain clients and bring in new ones.

Nobody knows exactly how large the faith-based investment market is after factoring in the assets of individuals and institutions. Most of the information isn’t public. But in a recent report, Morningstar quantitative analysts Manan Agarwal and Sabeeh Ashhar sized up a significant portion of the faith-based market: Christian and Islamic exchange-traded and mutual funds.

Although a small slice of the overall fund universe, faith-based funds are growing in number, and more investors are choosing to invest with their values as well as for returns.

Evolution of Values-Based Investing

Following religious and ethical guidelines in investing has probably been around as long as investing itself. The Quakers notably spoke out against profiting from the slave trade, and in 1760, John Wesley, founder of the Methodist movement in the Church of England, said members “ought not to gain money at the expense of life or by losing our souls.”

Flash forward to the 20th century: Another milestone came in 1971 when the Episcopal Church filed a shareholder resolution urging General Motors GM to stop manufacturing in apartheid South Africa. Catholics and other churches joined the movement, forming the Interfaith Center for Corporate Responsibility. Today, the ICCR includes more than 300 global institutional investors overseeing more than $4 trillion in managed assets. They include the Unitarian Universalist Association, the Presbyterian Church, the Sisters of St. Francis, and the Rabbis and Cantors Retirement Plan, as well as fund providers such as Everence Financial, sponsor of Praxis Mutual Funds, which has $2.5 billion in assets and has its roots in the Mennonite Church, and Wespath Investment Management, which provides funds that are informed by the values of the United Methodist Church.

The ICCR’s anti-apartheid push galvanized socially responsible investing. Tim Smith, senior policy advisor to the ICCR, says that “religious investors played that key catalytic role.” Socially responsible funds prioritize positive social change by considering both financial returns and moral values in investment decision-making. That has evolved into the modern sustainable investing movement, which relies heavily on environmental, social, and governance research. An ESG-based fund uses such data as part of its fiduciary duty to consider the material risks to its investment returns, such as climate risk and diversity risk.

The Largest Faith-Based Funds

Agarwal and Ashhar say faith-based investing is a version of socially responsible investing. Although it shares some of sustainable investing’s traits and uses ESG information, a faith-based fund has a dual mandate: In addition to its fiduciary duty, the fund also reflects the values held by a religious community.

“ESG doesn’t have a moral compass; it’s not necessarily mission-aligned, and it’s not impactful,” says Sonia Kowal, president of Zevin Asset Management, a sustainable-investment specialist that also oversees accounts for faith-based investors. “It’s just information that analysts can use.”

To some conservative religious investors, however, the term ESG has become anathema since influential Republicans demonized it while rallying behind the “anti-woke” flag in 2022. Inspire Advisors, which runs “biblically responsible” ETFs with tickers like BIBL, GLRY, and WWJD (for “What Would Jesus Do?”), originally added ESG to the names of its funds that didn’t already include it, then just months later removed the term from all its products in August 2022. Why the pivot? “ESG has become weaponized by liberal activists to push forward their harmful, social Marxist agenda,” CEO Robert Netzly said at the time. For good measure, Netzly compared ESG to CRT, or critical race theory, “as acronyms worth fighting against.”

Whether its adherents want to use the term or not, however, faith-based investing falls under the same umbrella as ESG.

Potential for Growth

There’s reason to believe faith-based investing will grow more popular. Customized investing is a growing area of wealth management, and faith is just one more way investors can include their preferences in the process.

Jean Case, the founder of FWIW (For What It’s Worth), a financial news and education site aimed at Generation Z, and head of the Case Foundation, says that one of the most widely searched terms on the site is, “What is faith-based investing?”

Says Mark Regier, vice president of stewardship investing for Praxis Mutual Funds and its parent Everence, “I can’t imagine talking about being values-driven and not wanting to know where the money is going.”

Some believe it’s a religious duty to invest. “We all believe in tithing and know we should give at least 10% to our church,” says David Spika, president of GuideStone Funds, which serves a Baptist clientele. “We should also be using our assets to influence the kingdom or to impact companies.”

In theory, the potential market is huge, considering the enormous moral authority exerted by religious institutions. The world’s population is around 8 billion. According to the Pew Research Center, Christians accounted for 31.4% of the global population in 2010 and Muslims for 23.2%. But relative to the investable universe, assets in faith-based ETFs and mutual funds are still a drop in the bucket.

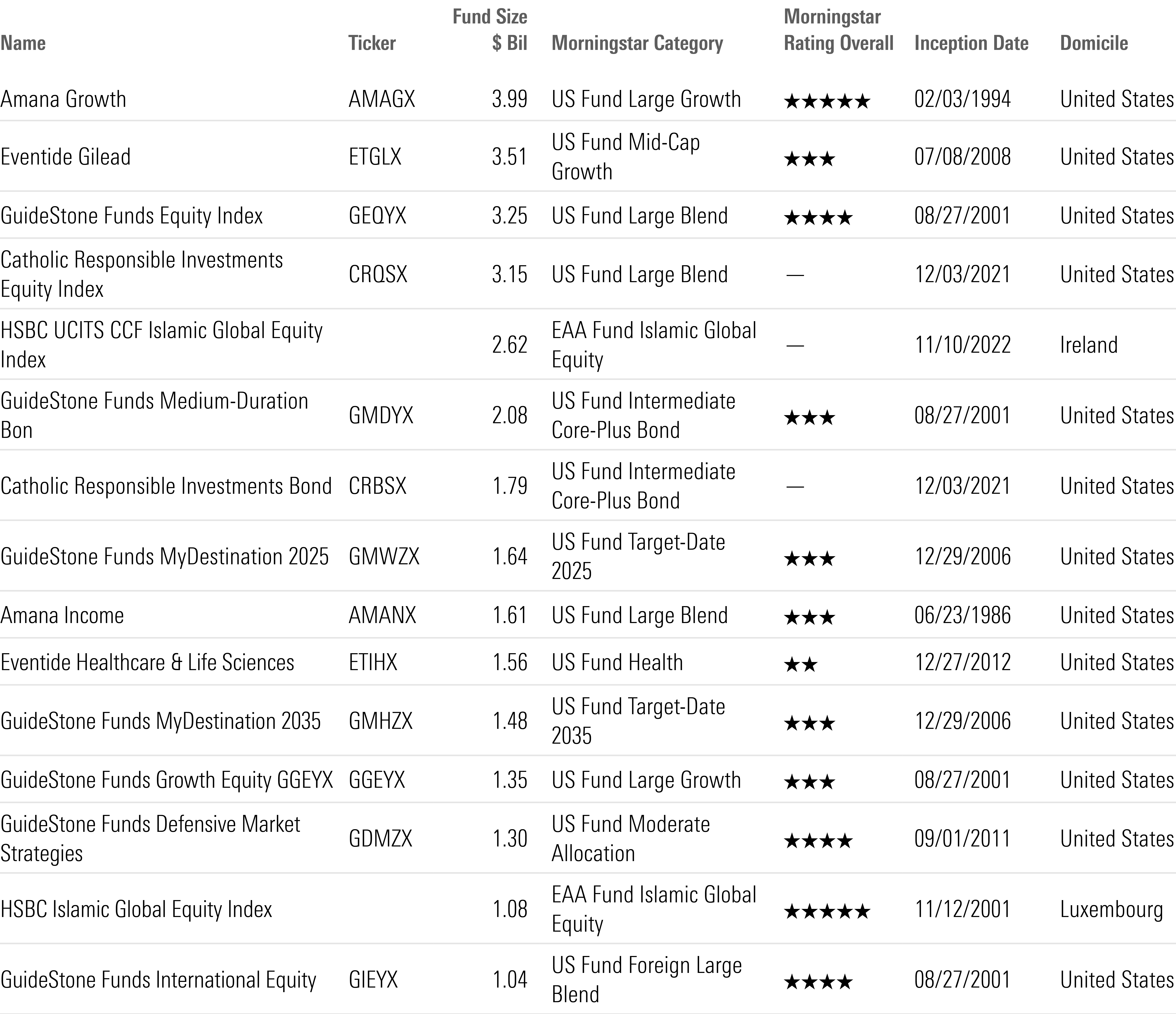

In their report, Agarwal and Ashhar tried to measure the Christian and Shariah fund market. (Shariah is Islamic canonical law.) They counted 850 faith-based funds and ETFs globally, with combined assets of just over $100 billion. (Vanguard 500 Index VFINX by itself has assets of $323 billion across its share classes.) Almost 85% of faith-based funds are Shariah-compliant, but they account for only $45 billion of the asset base.

Christian funds make up the rest. Roughly 95% of Christian-values funds are based in the United States, whereas 60% of Shariah funds are domiciled in Malaysia, Indonesia, and Saudi Arabia. That said, the largest faith-based offering is a U.S.-based Shariah fund: Amana Growth AMAGX, which has $3.9 billion in assets.

Investors in these funds need not necessarily sacrifice performance. The 15 largest funds have solid records overall. Most of them have the three-year record required to calculate a Morningstar Rating, which indicates a fund’s risk/reward profile within its Morningstar Category. Almost all of the ratings were 3-stars or higher as of the end of September.

David Kathman, senior manager research analyst with Morningstar Research Services, considers Amana Growth “a solid growth-leaning core stock fund for both Muslims and non-Muslims.” Both of the fund’s share classes earn Morningstar Medalist Ratings of Bronze. The cheaper institutional shares of Amana Income AMANX are also rated Bronze.

Eventide Healthcare & Life Sciences ETIHX earns a Bronze rating, though more expensive share classes of the fund are rated Neutral. The biotechnology fund “is not a bad option within its narrow niche,” says Kathman, but he notes that “most investors should approach it with caution due to its inherent volatility.”

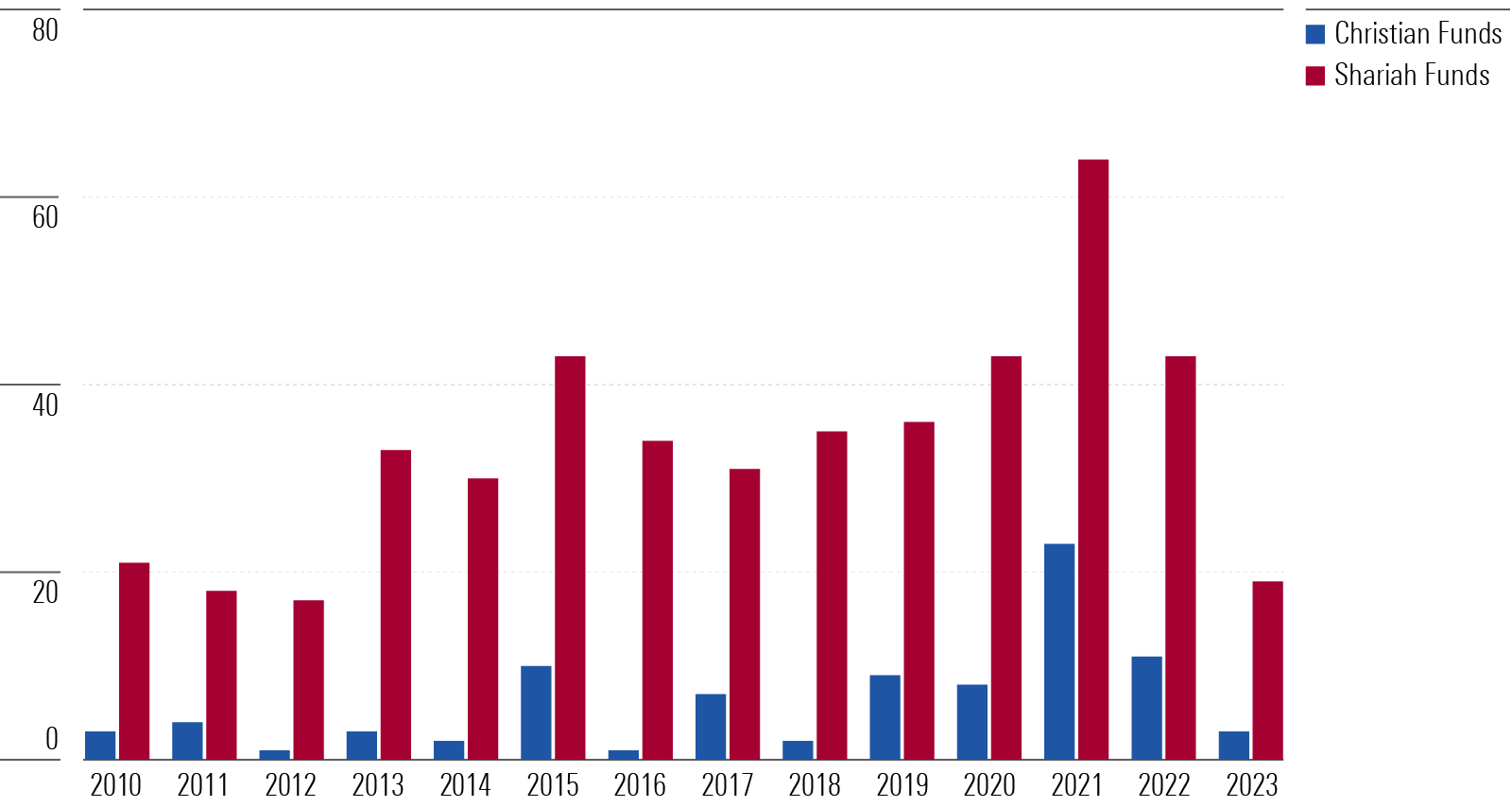

While the total assets in these funds are still relatively small, asset managers clearly anticipate a growing market. From 2019 to 2021, there was a surge in the number of new faith-based products being launched. The recent proliferation can be attributed to a combination of factors, including the rising demand for ethical and ESG investments, increased cultural and social awareness, and a growing desire to align financial decisions with personal values and beliefs, Agarwal and Ashhar say.

New Launches

How They Invest

Faith-based funds rely heavily on screening. Both Christian and Shariah funds have minimal involvement with alcohol and avoid investments associated with abortion, contraception, and stem-cell research. Together, they “maintain a notably low level of exposure to pork products, gambling, tobacco, small arms, and adult entertainment,” the Morningstar analysts write. Shariah-compliant funds restrict debt, so their holdings have stronger balance sheets.

A look at sectors reveals that technology accounts for almost 25% of the assets of Christian-values funds and almost 15% of Shariah-compliant funds. Apart from that, the analysts say, there appears to be a clear demarcation in investment philosophies. Basic materials and consumer defensives are top sectors for Shariah-values funds, but they are low on the list for Christian funds. While healthcare sits near the top of the list of sectors for Christian-values funds, it’s much lower down for Shariah funds.

Expense ratios are comparable to the average fund, at 70-80 basis points, compared with 60 basis points for the universe, the analysts say. The portfolios of both universes are dominated by small caps.

Agarwal and Ashhar conclude that faith-based funds are effective in aligning portfolios with values. “Only a very small percentage of the stocks that these funds are invested in have a high degree of exposure to products that contradict the religious principles they uphold,” they say.

How Does Your Garden Grow?

As the Kingdom Advisors conference shows, financial advisors are an important part of the faith-based space.

Advisor Sean Weaver has built a $40 million practice at One XVI Wealth in Southlake, Texas, which he named after a Bible passage that begins, “For I am not ashamed of the gospel.”

Roughly 60% of the practice is faith-based, Weaver says. His largest positions are in Eventide Investments and Dimensional Fund Advisors’ social core funds, which have screens similar to faith-based screens and are cost-effective.

“Most people have no idea what they own inside their mutual funds or ETFs,” Weaver says. “I’m fairly open about who I am, so I’m probably attracting people who are open to the idea from the beginning.”

There’s certainly room to expand. According to a 2019 study conducted by Faith Driven Investor, just 64% of Christian financial planners and advisors said they use faith-based investments with “some” clients.

Newer faith-based funds may appeal to these advisors. In 2021, Houston-based Crossmark Global Investments hired Bob Doll, an industry veteran, to join the firm as chief investment officer. The affable, widely quoted Doll has 40 years of investing experience, worked as chief equity strategist at Nuveen and BlackRock, and was president of Merrill Lynch Investment Managers. These days, he sits on the boards of Kingdom and the Alliance of Confessing Evangelicals. Before Doll, Crossmark had no actively managed large-cap equity expertise. Today, Crossmark uses Doll’s models that look at 55 secular variables, including earnings, valuation, and use of capital, as well as how companies are doing based on a set of religious values. Then, it ranks the companies.

Of Crossmark’s $6 billion under management, some $800 million-plus is in the actively managed large-cap strategy available through funds such as Steward Large Cap Growth Fund SJGIX and Steward Large Cap Core SJCIX. Nearly one fourth of that money isn’t from faith-based investors, the firm says. The funds are off to a relatively decent start. In 2022, its first full year, the large-cap growth fund lost 24.9% versus a loss of 29.9% for the large-growth category. The large-cap core fund lost 18% in 2022 versus the large-blend category’s 17% decline. In 2023, both funds are slightly lagging their peers for the year through Sept. 30.

Eventide is another fast-growing firm, with $6.8 billion in assets under management. Its largest fund is the $3.6 billion Eventide Gilead ETILX, a mid-cap growth fund with above-average long-term returns. Over the trailing 10 years through Oct. 10, 2023, the fund has an annualized 10.3% return versus 9.1% for the mid-cap growth category.

Some innovative strategies have drawn less investor attention but fill important niches. For example, Islamic-values funds prohibit the payment and receipt of interest. Amana Participation AMIPX, which has $215 million in assets, avoids interest by using sukuk instead of conventional bonds. Sukuk are income-producing investment certificates that are tethered to an underlying asset of a company, such as a rental lease agreement. Instead of earning interest, investors receive payments based on the profitability of that asset via the sukuk.

Call It Creation Care

Like in any values-based system, there is a wide range of views within faith-based investing, especially when it comes to ESG. Climate change is a notable example. The Episcopal Church lists “Creation Care” as a mission priority to address the church’s concern “for the global climate emergency.” In October, Pope Francis warned that “the world in which we live is collapsing and may be nearing the breaking point,” in a bid to influence the next UN Climate Change Conference. The Vatican has repeatedly addressed climate change. In a 2015 encyclical, the pope said that society must “hear both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor.” Indeed, the Vatican is using its influence to push Catholics to practice ethical investing. In 2022, it issued Mensuram Bonam, which calls for “a new investing culture that melds technical expertise with faith’s moral guidance.”

But while many Catholics and Protestants think climate change is a serious problem, a significant number of religious people don’t. “Across all religious identities, highly religious Americans are more likely than those with lower levels of religious commitment to say climate change is not a serious problem, especially because there are bigger problems in the world (30%) or because God is in control of the climate (27%),” according to a survey by Pew Research in 2022.

Other values collide with those of sustainable investing, such as reproductive rights. Firms like the Catholic Ave Maria Mutual Funds, with $3 billion under management, regard abortion as murder. Many sustainable investors, however, emphasize a woman’s right to choose and see state policies that severely restrict reproductive healthcare as risks for companies and employees. Many interfaith groups just avoid the subject.

“One reason there’s a lot of pushback [to ESG] is we have drifted into social issues clashing with religious issues,” says Lynn Forester de Rothschild, founder of the Council for Inclusive Capitalism. “I find that clash not helpful, so we don’t go there.”

Acting Together to Find Solutions

Nevertheless, religions sometimes bury their differences and act together. Faith-based investors have a long history of engaging with companies. Largely led by the ICCR, faith-based investors filed or cofiled nearly one third of ESG proposals in the U.S. between 2020 and 2022, according to US SIF, a U.S. trade group for sustainable investing. These institutions represent just 1.1% of the combined $3 trillion in assets controlled by all shareholder proponents, but they got results.

A big win came in the fallout of the opioid crisis, when the ICCR pushed for boards to take responsibility for opioid business risk. After that campaign, 18 companies adopted policies to recover compensation from corporate officials for misconduct.

In a move ESG investors would cheer, Eventide Funds urged solar panel producers to address slave labor in their western Chinese supply chains. Says Robin John, Eventide’s CEO, “We believe companies that serve stakeholders well”—meaning customers, employees, supply chains, host communities, environment, and society—”will ultimately do better in the long term. That’s good news for all investors regardless of your background.”

This story originally appeared in Morningstar Magazine.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/d53e0e66-732b-4d50-b97a-d324cfa9d1f8.jpg)

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/52a57b68-8d99-4364-96af-9ffc6a124531.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/NNGJ3G4COBBN5NSKSKMWOVYSMA.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6BCTH5O2DVGYHBA4UDPCFNXA7M.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EBTIDAIWWBBUZKXEEGCDYHQFDU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/d53e0e66-732b-4d50-b97a-d324cfa9d1f8.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/52a57b68-8d99-4364-96af-9ffc6a124531.jpg)