Aswath Damodaran’s Thoughts on Volatility, Valuation … and Even ESG

Key takeaways from a conversation with the NYU professor.

I had better than front row seats to Aswath Damodaran’s recent keynote conversation at the Morningstar Investment Conference, where I interviewed the distinguished New York University finance professor onstage. Our dialogue covered everything from investing to inflation, cryptocurrencies to CEOs, and ESG.

While some of the discussion was captured in Morningstar’s recent article “Maybe 2022 Was ‘the Start of the Return to Normal,’ Aswath Damodaran Says,” three additional key takeaways jumped out to me, particularly as it relates to equity investing.

1) In Periods of Market Volatility, Doing Nothing May Be the Right Choice

Damodaran: “The Hippocratic oath [says] ‘do no harm.’ In many ways, doing nothing is often the best option. The notion that you have to do something in a crisis can actually dig the hole deeper.”

It’s tempting to prove our worth as investors or analysts by doing something—anything!—when markets are volatile. But sometimes, we can get in our own way. While some times sharp price falls can signal a broken investment (more on that later), general market gyrations are often immune from this phenomenon.

My colleague Jeff Ptak made this case most clearly, showing that a “do-nothing” portfolio of buying and holding constituents of the S&P 500 over the past 10 years would have nearly matched the index’s return, and at a lower level of risk.

If anything, the words of Warren Buffett are important to recall in conjunction with Damodaran’s insights: “Be greedy when others are fearful.” We’d be wise to think about the long-term upside of suddenly cheaper stocks, rather than worrying about day-to-day volatility.

2) Traditional Investors May Find Common Ground in ESG by Focusing on Risk

Damodaran: “In a strange way, ESG is stronger on the ‘badness’ front than on the ‘goodness’ front. A piece of advice for companies: ‘don’t be bad.’ Don’t walk too close to the line because one misstep can put you over the line into a scandal or controversy, and you can come apart as a company. ESG’s strongest case is to measure that potential badness, and to say that’s a risk factor that could get them into trouble in the future.”

Damodaran’s critiques of environmental, social, and governance and sustainable investing have been numerous, and while there certainly are points of agreement, we haven’t always seen eye to eye; my response to one of his missives from a year ago outlines where we concur and disagree.

During this discussion, however, the professor and I found some common ground. In particular, he pointed out that high stock returns were unlikely to result from ESG considerations only. That strikes me as a reasonable argument. Like all other risks and opportunities a business faces, ESG concerns should be taken into account when valuing a business, but rarely are they the sole factor. This also aligns with my previously stated views. Considering ESG risks is essential to forming a complete view of potential investments, but it must be done in conjunction with traditional measures of valuation, too.

But Damodaran also offered concerns that ESG impact investing is effective: “The problem about investing being your primary vehicle for creating change is that there are only a subset of public companies that feel the pressure. … The risk we run is if we can pressure publicly traded companies to behave better, are we just pushing that bad behavior behind the curtain where privately owned and foreign companies continue to do it? In [this] case, we’ll still end up with a world we don’t like, but we’ll have paid a price to get there.”

This point builds on Morningstar strategist Kristoffer Inton’s second point in his recent article, “5 Things to Keep in Mind About Impact Investing”: “But as an investor looks to make impact with their equity portfolio, it’s important to know that usually, when you buy a stock, the proceeds go the previous holder who sold it to you, not to the company behind the stock. For all intents and purposes, nothing happened to the company, as it didn’t get new funds to put toward any project, let alone one with impact.”

3) Building a Good Valuation Requires More Than Just a Focus on Numbers

Damodaran: “A good valuation is a bridge between stories and numbers. … There’s a big difference between building an Excel model and valuing a company. … As data and tools have improved, valuations have become less cohesive and meaningful, because we’ve lost connections between stories and numbers that used to exist.”

I’m reminded of advice given to me early in my research career: financial models are “garbage in, garbage out.” Any reasonable estimate of a company’s value relies on analysis, contextualization, and insight to transform raw data into usable information. As Damodaran puts it in his book, Narrative and Numbers, “You need to bring both stories and numbers into play in investing and business, and valuation is the bridge between the two. ... Valuation allows each side to the draw on the other.”

It’s also critical, but difficult, to recognize when a narrative is broken, and it’s no longer the most likely outcome. As Damodaran put it during our conversation, “Falling in love with your own story is always a problem for investors … even as the world delivers facts that are discordant, you stick with your story. My advice is to hang out less with people who think just like you.”

No investor is likely to predict the future with 100% accuracy. But we must seek alternative information, lest we fall into the dreaded echo chamber. Only using information that supports our story, and casting aside any that doesn’t, is a surefire way to learn a painful investing lesson.

It’s for this reason that we occasionally see changes to the fair value estimates for the 1,500 stocks our equity analysts cover. As new information is presented and new perspectives are unearthed, our analysts’ predictive stories are sometimes rewritten. While no one likes to be proved wrong, I view these updates as a feature of our analysts’ ability to wade through large amounts of facts and figures to constantly test their theses and change their minds as needed.

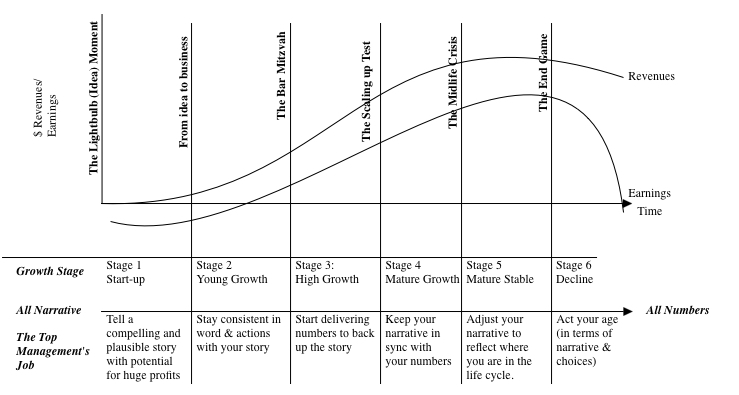

Companies Should Match Their Lifecycles With Appropriate Management

Damodaran’s work covers tremendous ground across corporate finance and valuation, and his next book, The Corporate Lifecycle: Business, Investment, and Management Implications, scheduled to be published in December, looks to build on this. In part, the book will focus on matching the age of companies with necessary management; as Damodaran argues, brand new companies need visionaries, still-young ones need builders, and older firms may need market-share defenders (or even asset liquidators). This expands some of his previous work, including a helpful blog post and chart from a few years ago:

Source: https://aswathdamodaran.blogspot.com/2015/12/the-compressed-tech-life-cycle.html.

More to come, I’m sure, but Damodaran offered a teaser for the Morningstar Investment Conference audience, using an extended analogy of companies compared to human aging. My favorite part: “Then you have teenage companies. What do they do? What teenagers around the world do, which is get up in the morning, look in the mirror, and ask, ‘Lots of potential. What can I do today to screw it all up?’”

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/35091ad9-8fe9-4231-9701-578ec44b5def.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/RNODFET5RVBMBKRZTQFUBVXUEU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/LJHOT24AYJCHBNGUQ67KUYGHEE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/V33GR4AWKNF5XACS3HZ356QWCM.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/35091ad9-8fe9-4231-9701-578ec44b5def.jpg)