How to Use Taxable Bonds in a Portfolio

This edition of our Portfolio Basics series covers the value of taxable bonds in reducing risk and generating income.

Should you have bonds in your portfolio? If you already have equity exposure, taxable bonds could be a logical addition, thanks to their ability to generate income and reduce risk.

In this series on portfolio basics, I’ll explain some of the fundamentals of putting together sound portfolios. I’ll start with some of the most widely used types of investments and walk through what you need to know to use them effectively in a portfolio.

What Are Taxable Bonds?

Taxable bonds make up the largest segment of the bond market. The taxable-bond market spans a wide range of investment options, including Treasuries, mortgage-backed securities, corporate bonds, high-yield corporates, bank loans, inflation-protected securities, and bonds issued outside of the United States.

When investors purchase a bond, they’re lending money to the bond issuer, which may be the government or a company. The issuer agrees to pay the investor back in full at a certain date (known as the maturity date), and bondholders receive periodic interest payments in the interim, typically at a set rate.

Because bondholders get more of their cash flows up front and also receive a set value at maturity, bonds are inherently safer than other types of securities, such as stocks. Bonds also rank higher in the capital structure than stocks, meaning their owners are among the first to be paid in the event of the issuer’s bankruptcy.

As the label suggests, taxable bonds are generally subject to taxes. Investors are usually on the hook for ordinary income taxes on a bond’s interest income in the year it was received. There are some exceptions: For example, interest payments from Treasury bonds and Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities are subject to federal tax but exempt from state and local income taxes. Bonds that typically aren’t subject to federal taxes are municipal bonds, which I’ll explore in a future article in this series.

What Are the Advantages and Risks of Investing in Taxable Bonds?

The main advantage of taxable bonds is their ability to generate current income with relatively low risk. For this reason, taxable bonds can be a good choice for many investors’ portfolios.

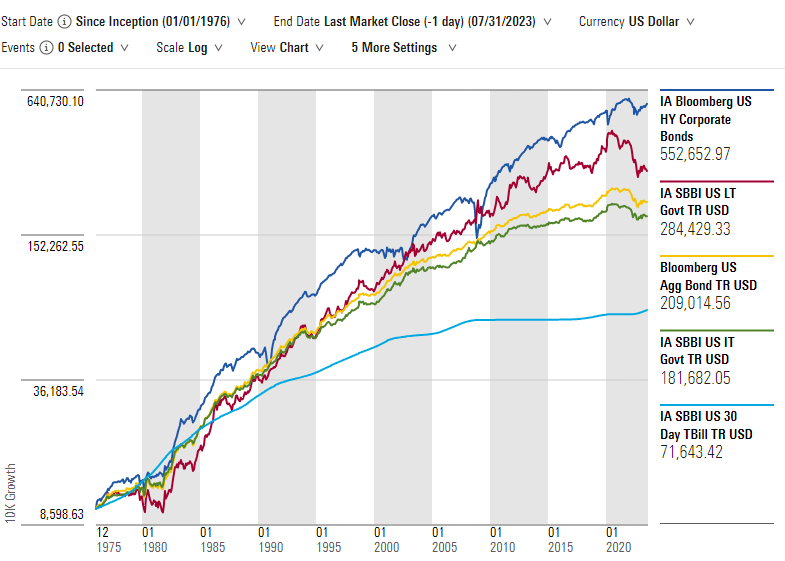

As shown in the graph below, bonds have generated higher long-term returns than cash—but they have less growth potential than stocks.

Growth Over Time: Bond Benchmarks

While bonds are less risky than stocks, they’re still subject to two main types of risk: interest-rate risk and credit risk. Because bond prices and market interest rates move in opposite directions, bonds lose value when interest rates rise. Credit risk—that is, the risk that a company won’t be able to repay its debt—can also be an issue for corporate bonds.

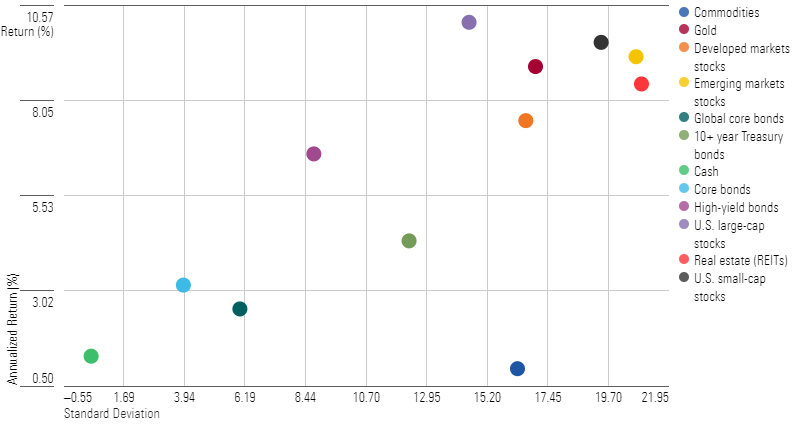

In practice, this means that taxable bonds typically come with middle-of-the-road risks and returns. The table below shows annualized returns and standard deviations for taxable bonds as well as other major asset classes over the past 20 years.

Trailing 20-Year Risk and Returns: Taxable Bonds and Other Asset Classes

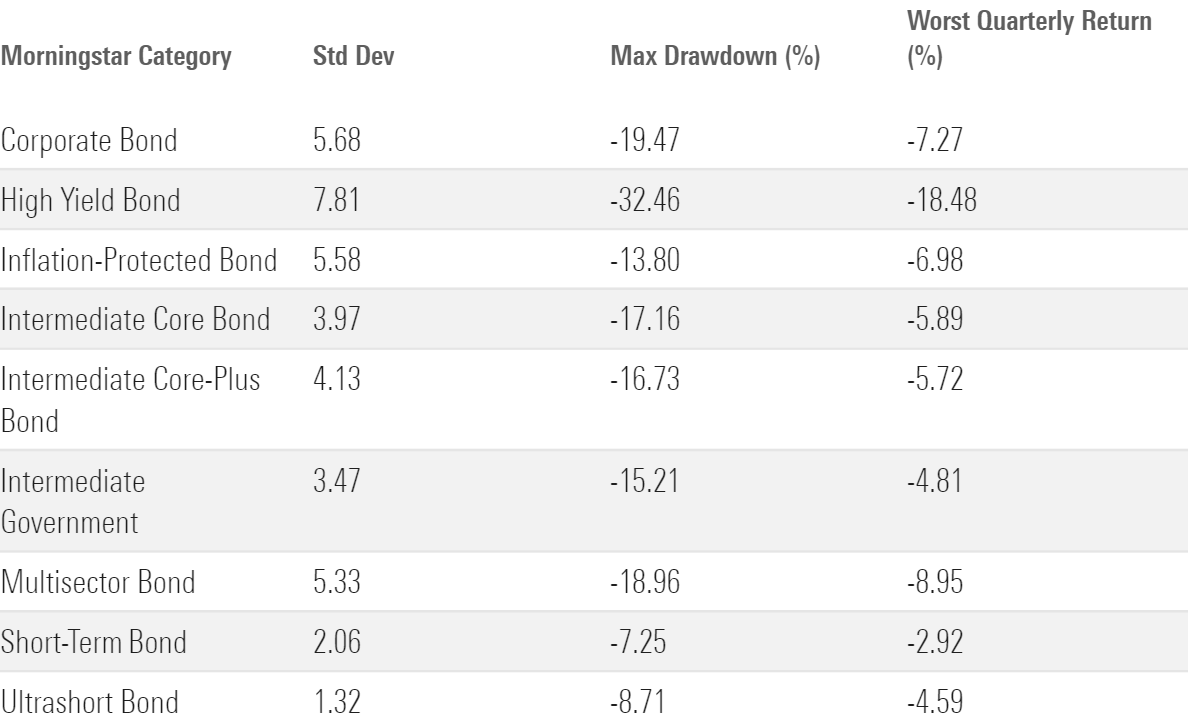

Historically, taxable bonds have lost as much as 15% or more during periods of rising interest rates. The year 2022 was particularly difficult because the Federal Reserve repeatedly hiked interest rates in an attempt to tamp down stubbornly high inflation. As a result, the Morningstar US Core Bond Index lost more than 19% for the year.

As shown in the table below, high-yield bonds have been subject to much greater downside risk than other investments: During the global financial crisis that started in late 2007, for example, the high-yield bond Morningstar Category dropped more than 30%.

Other Risk and Drawdown Stats (Since 1990)

How to Invest in Bonds

There are two main ways to invest in taxable bonds: by purchasing individual bonds or by purchasing a fund.

Purchasing individual bonds can be an appealing option because you simply collect your semiannual interest (known as a coupon payment) until the bond’s maturity date, when you’ll get the bond’s principal value back. This approach is easy to implement for Treasury notes and bonds, which are widely available on most major brokerage platforms.

If you’re purchasing other types of bonds, though, there are a few drawbacks, including higher trading costs in the form of bid-ask spreads. Investors can avoid those pitfalls by getting taxable-bond exposure with a mutual fund or exchange-traded fund. The advantages include:

- Lower trading costs.

- Professional management.

- Broader diversification across many different bonds and bond sectors.

- The flexibility to reinvest proceeds at higher interest rates if interest rates are trending up.

For most investors, broadly diversified index funds are the most straightforward way to invest in taxable-bond funds. While some active managers have been able to add value over time, index funds harness the market’s collective wisdom about the relative value of each bond included in a given benchmark.

They’re also cheaper: Investors in actively managed taxable-bond funds pony up annual expenses of about 71 basis points, on average, but the typical passively managed fund charges less than a third of that.

If you only own one taxable-bond fund, I’d focus on a mainstream bond category, such as intermediate core bond, rather than more specialized areas like high-yield bonds. Funds in the intermediate core bond category typically provide the broadest exposure to the overall bond market. If you have a shorter time horizon, you might want to go with a short-term bond or ultrashort bond fund.

When Do Taxable Bonds Perform Best?

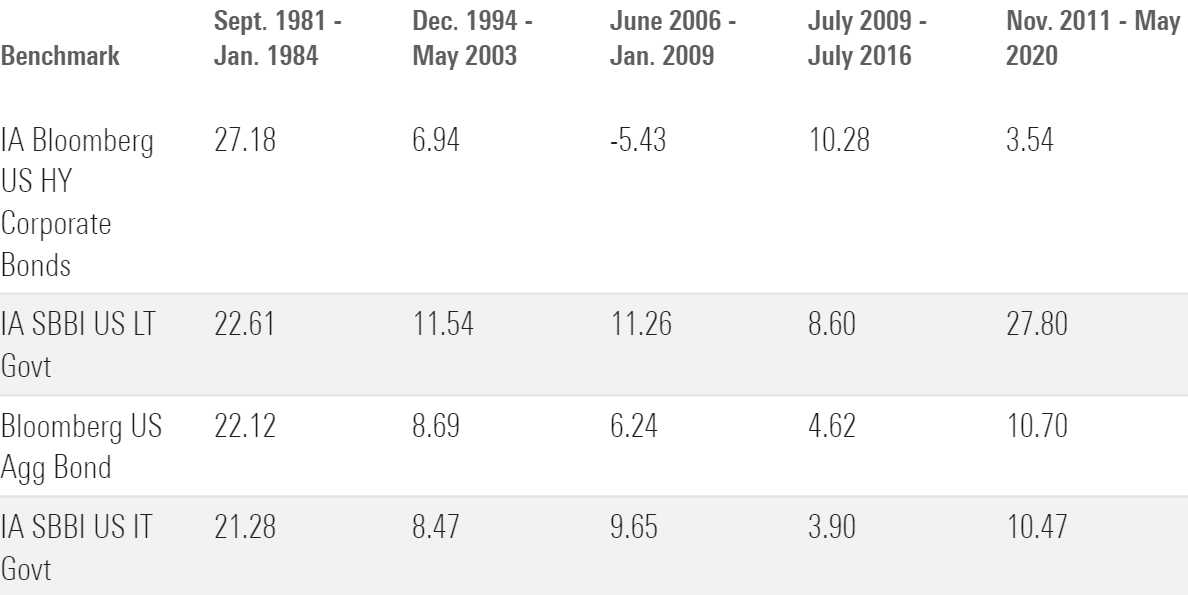

Because of the inverse relationship between bond prices and yields, taxable bonds perform best during periods of declining interest rates and low or declining inflation. The table below shows some of the most rewarding periods for bonds over the past four decades or so.

Annualized Total Returns for Taxable Bonds in Recent Bond Bull Markets

Bonds have suffered some short-term declines in years like 1994 and 2013, amid rising interest rates and/or concerns about credit quality. However, the entire period from 1981 through 2020 could be considered a long-term bull market for bonds, as interest rates trended down and inflation was usually a nonissue. That situation abruptly changed in 2022 thanks to the rapid increase in interest rates over an unusually short period. However, bond yields are now high enough that they should provide some cushion against additional rate increases.

How Long Should I Hold My Investments in Bonds?

If you’re buying an individual bond, it makes sense to match up the bond’s maturity date with when you’ll need to tap into the assets. That’s because bondholders typically receive the bond’s full par value at maturity. (Callable bonds are an exception.)

For bond funds, Morningstar’s Role in Portfolio framework recommends holding most types of taxable bonds for at least two to six years. Some bond-fund categories, such as short-term bond and ultrashort bond, can be suitable for shorter holding periods.

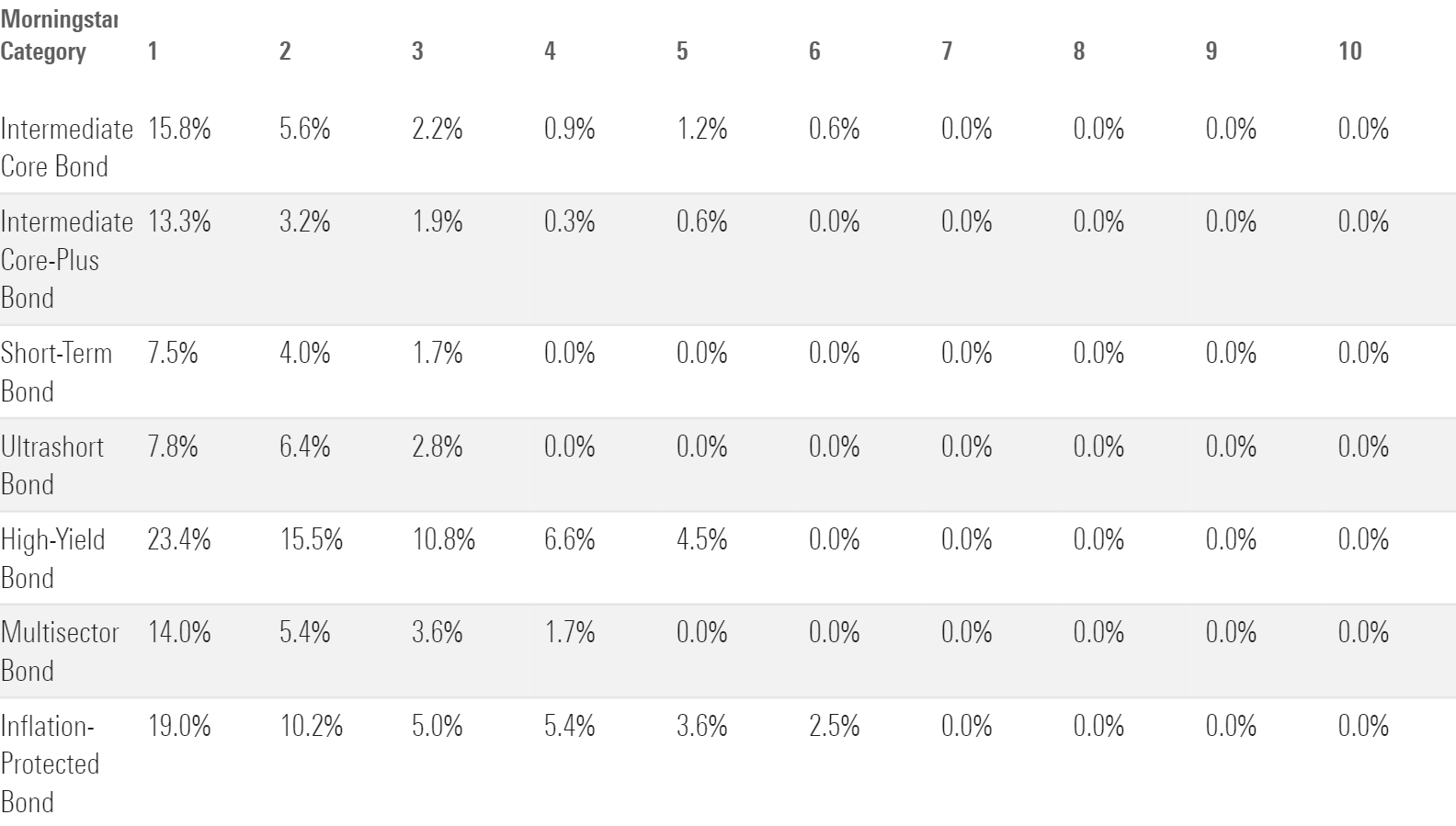

We came up with these guidelines partly by looking at the historical frequency of losses over various rolling time periods ranging from one year to 10 years. The idea is to minimize the odds that an investment is in the red when you need to access the money to fund a goal. Over a one-year period, for example, returns for intermediate core bond funds have been negative nearly 16% of the time. Over a period of two years or more, the odds of incurring a loss are significantly lower.

Frequency of Losses Over Rolling Periods Since 1990

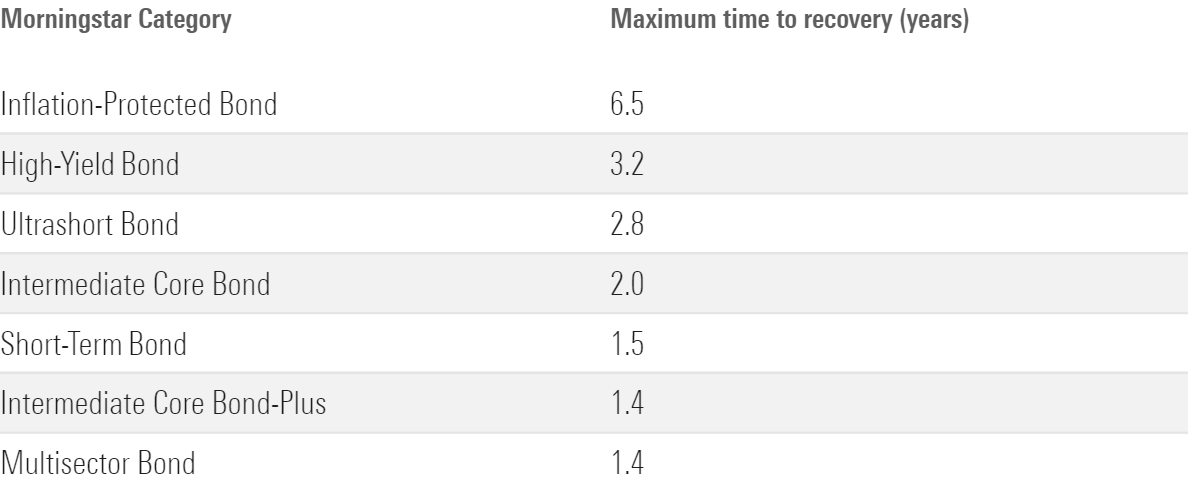

Another way to think about this issue is by looking at the maximum time to recovery, or how long it typically takes for a given fund category to recover after suffering a drawdown. As shown in the table below, intermediate core bond funds have historically recovered within about two years, although they still haven’t fully recovered from the drawdown that started in early 2021. Because of their greater sensitivity to interest-rate risk, inflation-protected bond funds have taken as long as 6.5 years to win back their losses after a market downturn.

Maximum Time to Recovery for Taxable-Bond Categories Since 1990

How Much of My Portfolio Should Be in Bonds?

The answer to this question largely depends on your portfolio’s overall asset mix.

If you’re investing for a long-term goal, you’ll probably want to tilt your portfolio more toward stocks. Target-date fund allocations can also be a useful guideline for the appropriate level of bond exposure: The typical target-date fund starts with a bond allocation of about 8% for an investor with 40 years to retirement, gradually increasing the bond allocation to 55% of assets at retirement and 66% of assets 30 years after retirement.

It’s also worth considering whether taxable bonds or municipal bonds make sense for your situation. If you’re in a higher tax bracket and are investing in a taxable account, you’ll probably want to keep at least part of your bond exposure in municipal bonds, which have interest payments that are generally exempt from federal (and in some cases, state or local) income taxes.

Within each bond portion, it makes sense to use the overall composition of the market as a starting point. On the taxable side, intermediate core bond funds are a good proxy for the performance of bonds in general. As a result, we consider them core holdings that could make up as much as 40% to 80% of a portfolio’s assets.

Other areas, such as multisector bond funds and inflation-protected bond funds, fill more specialized roles; we consider them “building blocks” that could make up as much as 15% to 40% of a portfolio’s assets.

What Are the Best Taxable-Bond Funds?

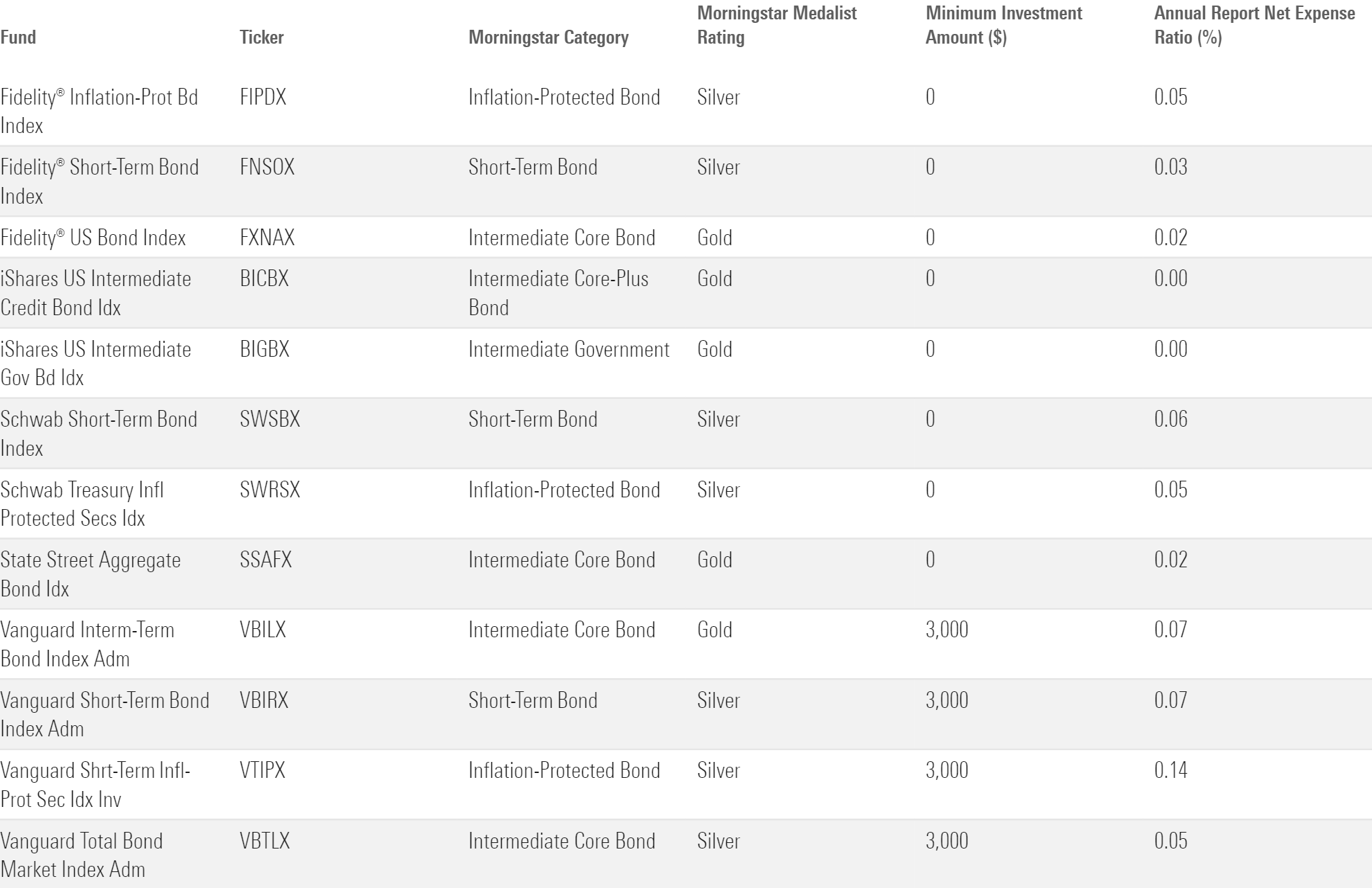

The table below shows a subset of highly rated index funds focusing on taxable bonds. I’ve focused on large-cap blend funds that are broadly available through major brokerage platforms, with low investment minimums and ultralow expense ratios.

Highly Rated Taxable-Bond Funds (Index Funds)

The list below includes a few actively managed funds from Russ Kinnel’s “Thrilling 31″ list, which features funds with relatively low expense ratios, high Morningstar Medalist ratings, portfolio managers who have invested at least $1 million in their own fund, and above-average returns during the manager’s tenure for at least five years.

Highly Rated Taxable-Bond Funds (Actively Managed Funds)

What Funds Pair Well With Taxable Bonds?

If you’ve already added a taxable-bond fund to your portfolio, a large-cap stock fund or international-stock fund could be a logical addition, depending on your time horizon.

While bond funds typically court less risk, stock funds are better growth engines over time. In addition, the correlation between bonds and stocks has often been negative—that is, when stock returns are down, bond returns are stable or increasing. This relationship can help improve risk-adjusted returns for a portfolio that includes both stocks and bonds.

- Large-cap stocks are the best way to get broad exposure to stocks in general. By definition, large-cap stocks make up the majority of the available market, so it makes sense that they should make up a significant portion of most investors’ total equity exposure.

- International-stock funds provide more complete exposure to the global market. U.S. stocks currently make up about 60% of global market capitalization, but non-U.S. stocks account for the remaining 40%.

As mentioned above, municipal bonds can also make a good complement to taxable bonds, especially for higher-income investors saving in a taxable account.

Are Taxable Bonds a Good Investment?

Taxable bonds aren’t the best way to generate long-term wealth, but they serve a critical role in providing both current income and helping reduce risk at the portfolio level.

With the exception of investors who are young, saving for a long-term goal, and highly risk-tolerant, taxable bonds are a key foundation for nearly every investor’s portfolio.

The Best Investments for the Core of Your Portfolio

The author or authors own shares in one or more securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)