How Twitter Stock Investors Got Lucky

3 Lessons for investors from Elon Musk’s bid and the Twitter soap opera.

Twitter is now a bird of a different feather. And Twitter shareholders should consider themselves lucky.

Less than 10 years after launching as a publicly held company, the social-media platform that promised to “serve the public conversation” is private again. Its main mission appears to be serving as a mouthpiece for its impulsive and mercurial new owner, Elon Musk.

Twitter’s spell as a public company officially ends—at least for now—on Tuesday when its shares are delisted from the New York Stock Exchange.

While Twitter’s return to its status as a private company has been something of a soap opera combined with a circus, here are three lessons for investors from its tumultuous time as a publicly traded stock:

Profits Matter

Twitter ended up in this predicament because it never lived up to its potential as a public company. It wasn’t profitable and it lagged its competitors—Meta Platforms META, Snap SNAP, Pinterest PINS—in terms of growing its user base, attracting advertisers, and increasing revenue.

The purchase price represents a 38% premium to Twitter’s stock price at the close of trading on April 1, which was the last trading day before Musk disclosed his approximately 9% stake in Twitter.

That it was able to fetch such a lofty price for its shareholders defied all expectations and depended on the whim of a billionaire.

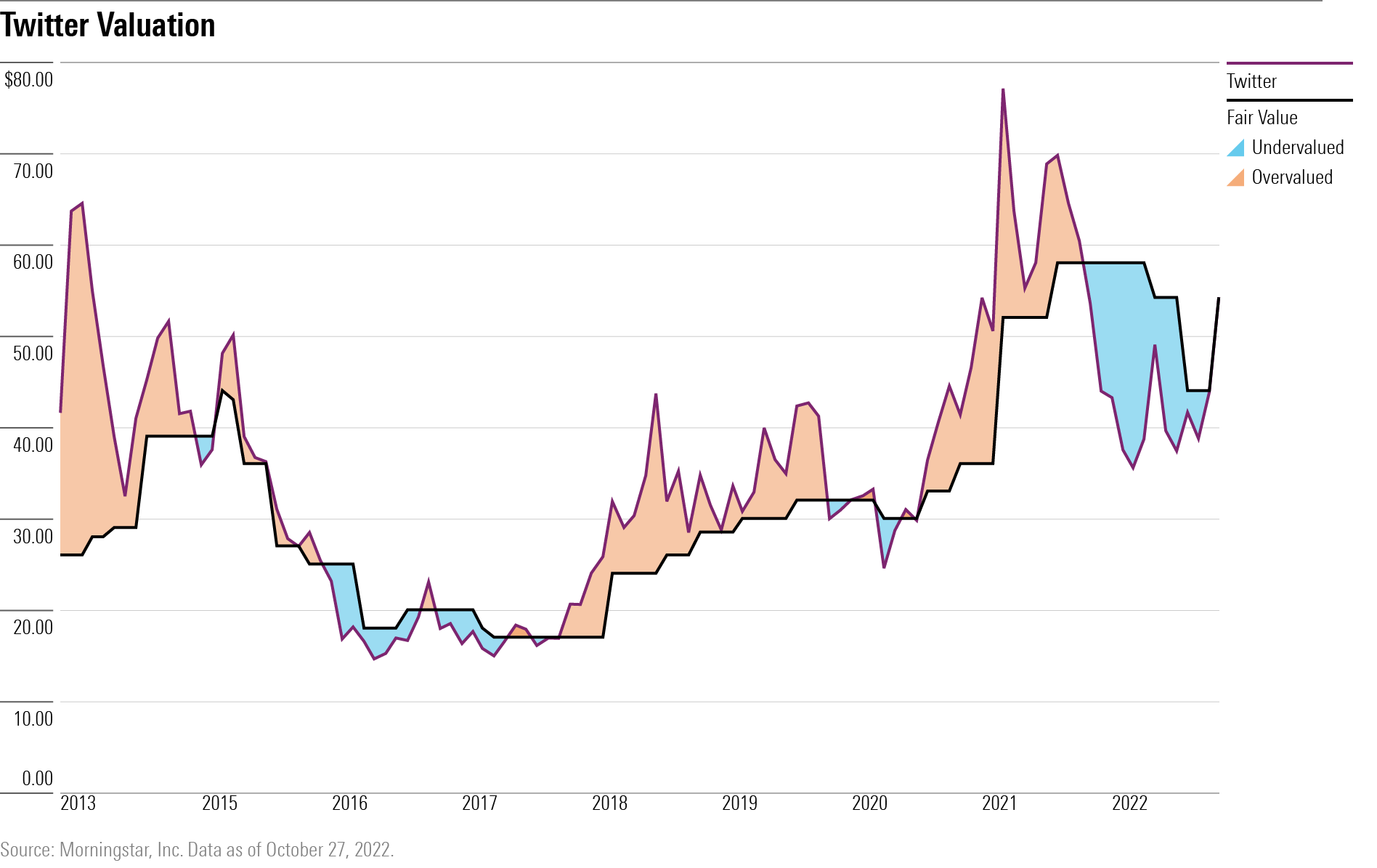

Twitter’s stock went public in November 2013 at $26 a share and raised $1.8 billion through the sale of 70 million shares, though it had yet to make a profit. At its launch, the shares popped 73% to close the day at $44.90.

Twitter went private nine years later on Oct. 27 for only about $10 more, when Musk paid $54.20 a share, or $44 billion. That amounts to a return of roughly 2% a year. That compares with an average annual return of 10% a year on the Morningstar US Market Index.

Even Musk, the world’s richest man with a net worth pegged at $203 billion and the chief executive of electric vehicle maker Tesla TSLA, regretted his bid almost as soon as he made it.

The on-again, off-again saga started early this year with Musk building a stake in the company at an average price of $36 before he publicly revealed his interest in buying the company and inked a deal in April. Within a month, he tried to back out of it, claiming many of the user accounts at Twitter were phony. He was ordered by a judge in early October to complete the transaction by Oct. 28 or risk a costly trial that he was likely to lose. Musk acknowledged he was overpaying for Twitter when he discussed Tesla’s third-quarter earnings with Wall Street analysts in October, noting, “it’s massive that this sort of languished for a long time.” He added that he thought it had “incredible potential.”

Management Matters

Its management was a study in dysfunction and distraction and was long a source of criticism. In its short life as a public company, it had three different chief executives.

One chief executive, co-founder Jack Dorsey, was pushed out twice as head of the company, once when Twitter was still private in 2008 and more recently in November 2021, when activist investor Elliott Management clamored for more product innovation and better management. Triggering the Elliott action was Dorsey’s announcement in 2020 that he planned to move to Africa for six months and decentralize management.

Corporate Governance Matters, Too

Twitter appeared to be an easy acquisition target as its shares long lagged those of its peers, including Meta Platforms, Snap, and Pinterest as it struggled to add to its user base and draw advertising.

But another set of factors worked in favor of Twitter shareholders, even if they didn’t realize it: Twitter’s corporate governance initially did not include barriers to an unfriendly takeover.

Corporate governance experts often oppose steps by companies that make takeovers more difficult. While a takeover can prove to be disruptive, measures that make such a move more difficult takes the decision-making out of the hands of a company’s actual owners, aka shareholders.

“Shareholders want the market to do its job, and when a bid comes in, company shareholders are inclined to sell as long as the price is right and don’t want anything to get in the way of that mechanism,” says Lindsey Stewart, Morningstar’s director of investment stewardship research.

Only after Musk made his bid for the company did Twitter’s board adopt a poison pill. Under the plan, if an investor or group acquired at least 15% of Twitter’s stock without board approval, other shareholders would be allowed to acquire shares at a discount. That could have diluted Musk’s stake if he continued in a hostile fashion, and it gave the board leverage to negotiate.

Another issue at Twitter that set it apart from other media companies was the lack of a controlling shareholder who might have served to fend off activists and provide protection against takeover threats. On that front, Dorsey, who owns 2.4% of Twitter and continues to own the shares, also seemed to champion Musk’s bid. Following Musk’s offer, Dorsey tweeted that “Elon is the singular solution I trust. I trust his mission to extend the light of consciousness.”

Meanwhile, Dorsey, also the co-founder and executive chairman of payment processor Block SQ, formerly known as Square, is developing Bluesky, a new social-media platform seen as a potential competitor to Twitter.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ed88495a-f0ba-4a6a-9a05-52796711ffb1.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T5MECJUE65CADONYJ7GARN2A3E.jpeg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/VUWQI723Q5E43P5QRTRHGLJ7TI.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-22-2024/t_ffc6e675543a4913a5312be02f5c571a_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ed88495a-f0ba-4a6a-9a05-52796711ffb1.jpg)