Stock Buybacks and ESG: How Long-Term Thinking Can Separate Good Companies From Bad

No, we don’t need to ban buybacks. The cautionary tale of Bed Bath & Beyond.

Share buybacks receive an outsize amount of attention compared with other investing topics. As the tactic has grown prevalent over the past several decades, it’s also the target of criticism, taxation, and government oversight. There is even talk about banning buybacks, as the government did for large companies that borrowed bailout money during the pandemic under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or Cares, Act. But do repurchases really deserve all the criticism?

I think the pushback misunderstands the issue. For some companies, repurchasing shares is the right choice. For others, it’s exactly the wrong one—a painful lesson that Bed Bath & Beyond, discussed later in this article, illustrates.

Ultimately, repurchases are a strategic use of cash—akin to investing in a new factory, acquiring another business, retiring debt, or paying a dividend. Hindsight, of course, offers perfect vision. But some metrics can help investors understand which companies might be best positioned to add value through share repurchases.

To that end, applying a corporate governance lens—the third pillar of environmental, social, and governance analysis—may help to shed light on buybacks. Although not often highlighted in ESG circles, understanding the success—and potential pitfalls—of share repurchases centers on many of the same principles we apply to measuring environmental or social matters: an understanding of trade-offs; a consideration of management incentives; a measurement of financial materiality; and a focus on the long term. By considering companies’ broader stakeholder management—a hallmark of ESG analysis—alongside a more traditional measurement of capital allocation, we can avoid any myopic thinking that may guide us to incorrect conclusions about the potential impact of share buybacks.

When Companies Buying Back Stock Makes Sense

Sometimes, returning cash to shareholders is the right move for a company. So long as that cash is truly “excess,” in that it couldn’t be better spent elsewhere, it’s often best to let investors allocate it to other higher-returning opportunities. This is true for either dividends or share buybacks, though repurchasing shares offers more flexibility for companies and tax advantages for shareholders versus paying dividends.

Buybacks aren’t perfect, though. While repurchases should only be done with excess cash, critics rightly say that companies often do buybacks at the expense of other uses of capital.

How can we address this risk when considering investment in a company? Comparing metrics such as the debt/equity ratio, capital expenditure as a percentage of sales, and return on invested capital versus peers can help to uncover companies that may be pursuing buybacks at the expense of long-term financial health. Markedly different financial metrics versus industry peers combined with massive share buybacks could be a red flag that a company is distributing more than true excess cash.

To that end, our equity analysts consider in their Morningstar Capital Allocation Rating for each company several pertinent questions related to shareholder distributions (both buybacks and dividends), such as:

- What is the opportunity cost to the balance sheet and investment from shareholder distributions?

- Could more value be added by lowering distributions to strengthen the balance sheet or invest more?

- If investment options are limited, are shareholders better off if most of the cash flows are distributed?

Why Stock Buybacks Don’t Inherently Boost Long-Term Value

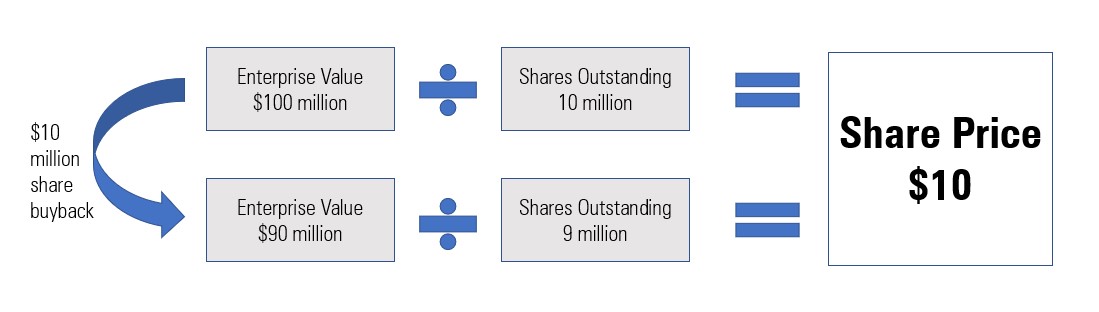

Another common critique of buybacks is that companies are rewarding shareholders and management at the expense of workers and economic growth. Detractors argue that firms boost their stock valuation by reducing the number of shares outstanding, making wealthy investors and CEOs even richer without reinvesting in the economy. After all, fewer shares on issue leads to greater value per share, right?

The truth isn’t so simple, as the equation below shows. Only repurchasing shares for less than intrinsic worth (which we refer to as the fair value estimate) will add long-term value for a company. In fact, buying back shares for greater than fair value destroys value over time.

Share Buyback Calculation

The second part of this critique also ignores the long-term effect of market forces on company performance. Firms that take on too much debt, underinvest in their core business, or struggle to properly pay their employees will likely see their stock underperform over the long run, regardless of how many shares they’ve repurchased.

Meanwhile, capital returned to shareholders who opt to sell their shares can also be put to productive use, which may include both consumption and new investment—boosting the economy. For these reasons, I don’t think additional taxes or regulation for buybacks are necessary; investors will ultimately decide the winners and losers of share repurchase decisions.

The Cautionary Tale of Bed Bath & Beyond’s Stock Buybacks

If you’re not convinced that the market will suitably punish companies for making bad share buyback decisions, then perhaps a real-world example will illustrate the point.

The financial mismanagement of Bed Bath & Beyond over the past several years is not a new story—the company declared bankruptcy in April 2023, after all. But the horrendously poor share buyback policy that contributed to this outcome is less commonly discussed.

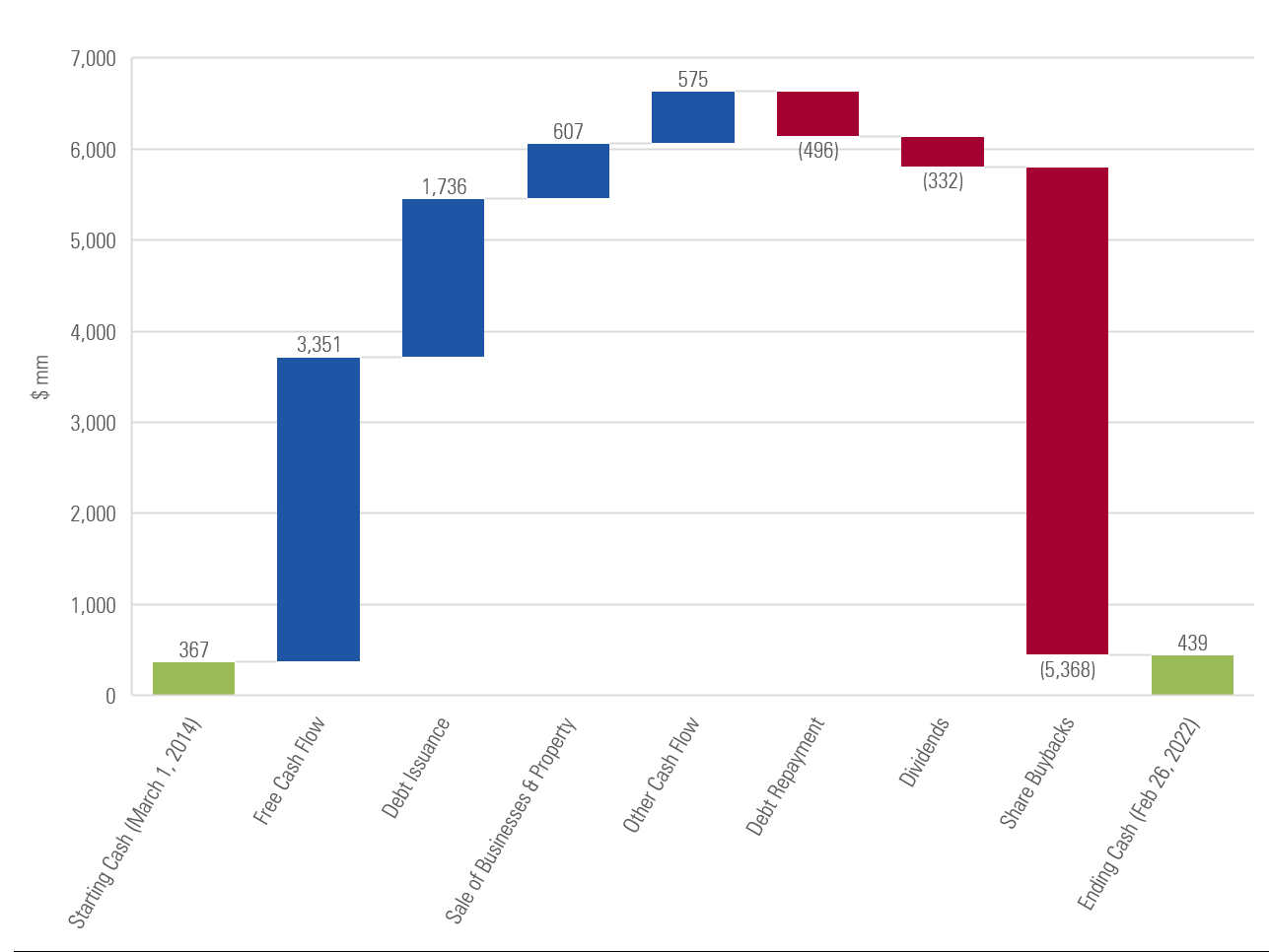

Bed Bath & Beyond’s stock hit its all-time high in late calendar 2013, at a price of about $79 per share. From March 2014 through February 2022 (fiscal years 2013 through 2021), the company generated $3.4 billion in free cash flow (that is, operating cash flow less capital expenditures). On top of that, it took on a net $1.2 billion in debt, sold for $600 million companies it had previously acquired, and had about $600 million in other cash flow (including movements of short-term investment securities). All in, this totaled about $5.8 billion of available cash.

Spurred on by activist investors, nearly all of this cash was used for share buybacks—roughly $5.4 billion. The company also paid out $332 million in dividends over the period, leaving only $72 million of cash to be added to the coffers.

Bed Bath & Beyond's Use of Cash From March 2014 through February 2022

Operating results worsened over this period, and the company subsequently reported that free cash flow plummeted to negative $1.2 billion in the period from March 2022 through November 2022. In an attempt to salvage the business, the firm cut its dividend and share repurchase plans, issued $1.2 billion of debt, and sold about $119 million of new shares. But it wasn’t enough to stave off bankruptcy.

In the end, market forces won out. Bed Bath & Beyond’s management made poor capital allocation decisions. (Reflecting this, our equity analysts had downgraded Bed Bath & Beyond’s Capital Allocation Rating to Poor in September 2022.) If the firm had instead reinvested in its core business to improve its competitiveness, it may have been able to stem its falling revenue and operating earnings. But management (and the group of activist shareholders) was clearly hellbent on returning cash to shareholders; a ban or increased tax on buybacks likely would have simply led to increased special dividends or capital returns as alternatives.

Sacrificing a company’s long-term financial health for an attempted short-term fix isn’t likely to work as time progresses. Proper capital allocation analysis, understanding of management incentives, and long-term thinking—all hallmarks of successful investing, ESG or otherwise—are critical to determining the potential success of a firm’s buyback strategy.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/35091ad9-8fe9-4231-9701-578ec44b5def.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EBTIDAIWWBBUZKXEEGCDYHQFDU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/PJQ2TFVCOFACVODYK7FJ2Q3J2U.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/PVJSLSCNFRF7DGSEJSCWXZHDFQ.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/35091ad9-8fe9-4231-9701-578ec44b5def.jpg)