Editor’s note: This article compares women’s retirement circumstances with men’s and does not address the experiences of nonbinary people because of the industry’s gap in that data. Morningstar encourages more work in this area and will continue to update this page as more research becomes available.

The debate over the magnitude of the retirement crisis in the United States is ongoing, but one aspect is settled: Women are in worse shape than men on nearly every important metric.

The reasons are manifold, but a few factors loom large.

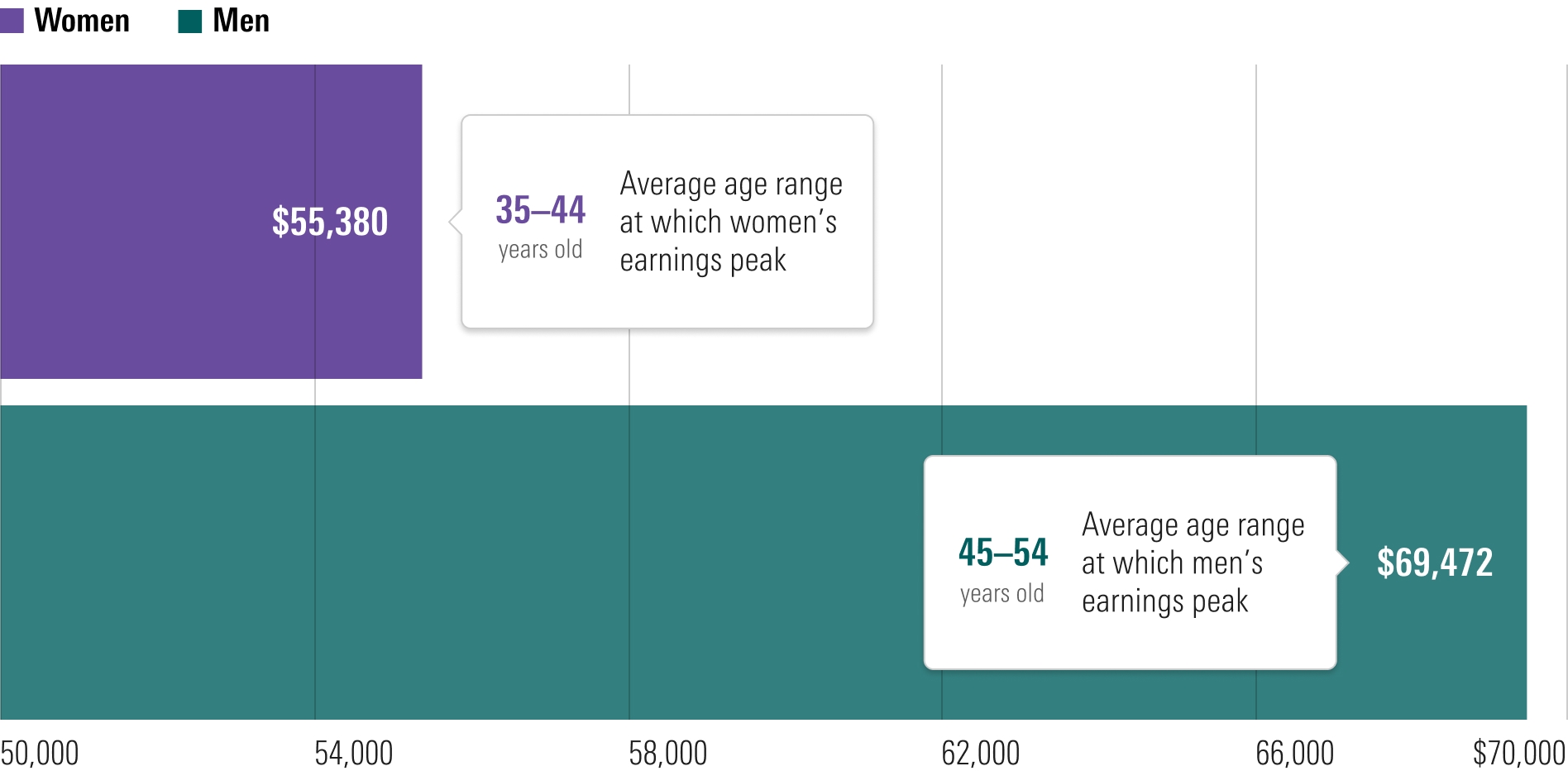

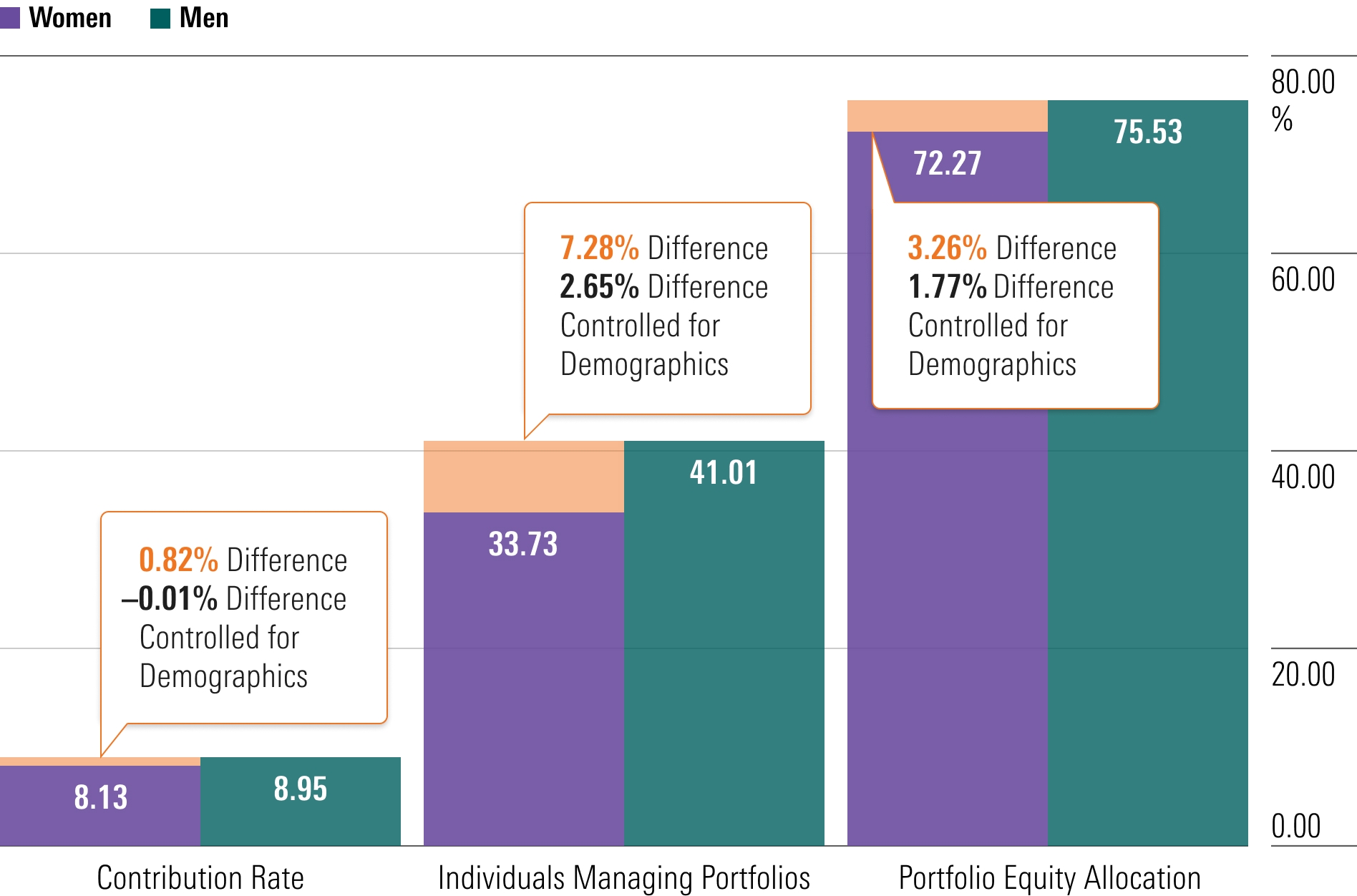

Women have lower lifetime earnings than their male counterparts, which translates to fewer opportunities to fund retirement accounts. This can be attributed to both wage inequality and the fact that women are more likely to stop working to devote time to caregiving for family members. These caregiving needs substantially intensified during the pandemic: In 2021, the percentage of women in the labor force dropped to 56.1% (the lowest since 1987), though women’s workforce participation rate has since rebounded.

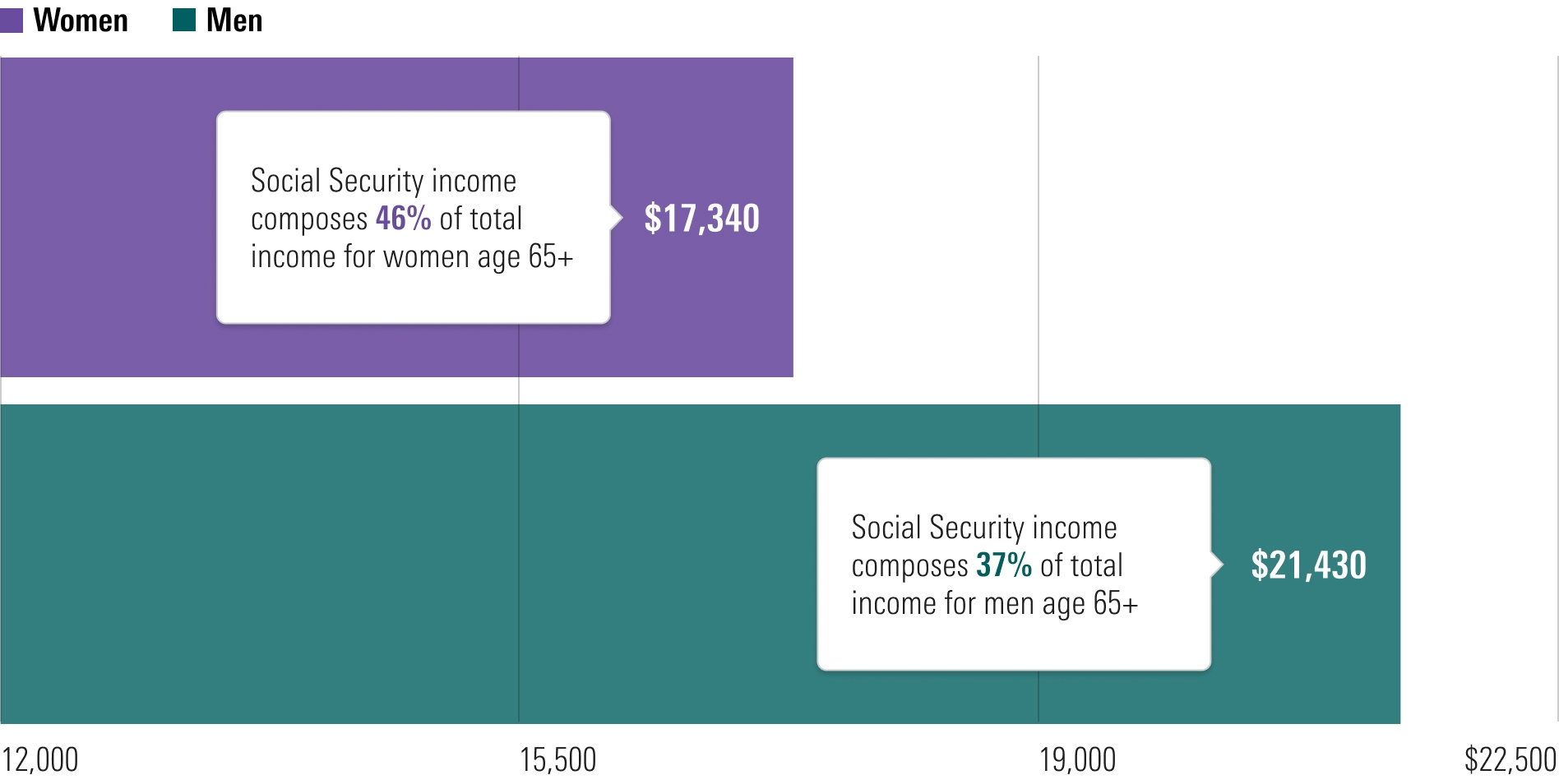

In addition, women have longer life expectancies than men. This means they must stretch those smaller average balances over a longer time frame. Women aged 65 outlive their male counterparts by more than two years, on average, and approximately two thirds of people in nursing homes are women.

That convergence of lower retirement balances and a longer retirement period helps explain why women are much more likely than men to be poor in retirement.

There’s no easy fix for this issue. But women can consider these five questions to improve their retirement readiness.