Why Do Women Invest Less Than Men? Blame the Income Gap

As women gain wealth, advisors must prepare to serve them.

While demographic trends and societal norms shift, so has the way U.S. households make financial decisions.

Not only are women expected to control much of baby boomer assets in coming years, but more and more studies have noted how women are also playing a larger role in household financial decisions and becoming family breadwinners. Yet, even as more women gain wealth, common stereotypes still loom large.

In our latest research, we focused on nailing down what's behind these conceptions of women investors and, in the process, identified potential ways that financial professionals can better serve female clients.

Women Investors Are Coming, the Finance Industry Is Not Ready

Previous research suggests that women may feel misunderstood in the finance world--which may be driving their behavior. Research has found:

- Women investors are 18% more willing than men to consider switching to another financial advisor, and 70% of widowed women investors change advisors within one year of their partner's death.

- Advisors were 40% more likely to require female investors to transfer their balance to them before giving any specific advice compared with male investors, which may be based on the assumption that women are more gullible.

- Female investors reported their advisors assume they have a low-risk tolerance and are interested in sustainable funds. As a result, women are offered a limited set of investment options.

In our research, we worked to clear up some misconceptions about how women invest and help advisors manage the needs and expectations of women clients.

Does Gender or Income Drive Investing Behavior?

We surveyed 907 U.S. residents (437 female) to measure financial health, behavior, and attitudes. In an analysis of the data by gender, we found that most of the supposed differences between men and women investors regarding saving and investment behavior disappeared when controlling for income. The differences that persisted were mostly attitudinal and suggest humility, composure, and a confidence gap.

Digging a little deeper: At first glance, men and women appear to have significantly different financial attitudes and behaviors. On average, men reported more frequent saving and investing behavior, they were more likely to think of themselves as investors, more confident in their knowledge of investments, more likely to have changed their investments in the 12 months leading up to the study, and more confident in their ability to financially handle the unexpected.

These findings are deceiving, though. In our sample, women's income scores were roughly 20% lower than men's, on average. But when we compared men and women in the same income bracket (rather than comparing all men to all women), these differences in spending behavior, investing behavior, and confidence handling the unknown were no longer significant.

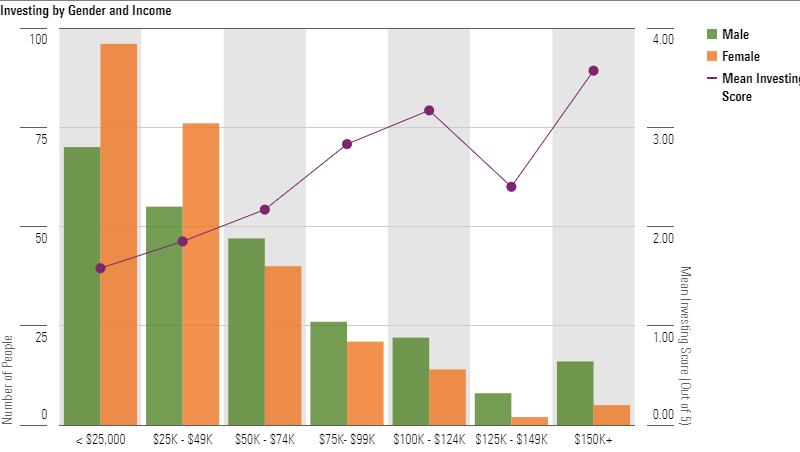

This suggests that income is a stronger predictor of these attitudes and behaviors than gender. Yes, women in our sample saved and invested less frequently than men, but the chart below shows that most saving and investment happened in the higher-income tiers--where men significantly outnumbered women.

Source: Morningstar. In the lower-income tiers, where people were less likely to save and invest, women represented more than 50% of the population. In the higher-income tiers, where more saving and investing was reported, men were more than 50% of the population. The result is an overall difference in investment rates by gender, but this difference disappears when income is controlled for.

It is also interesting to note that, scores on overall financial health (the Financial Health Network's FinHealth Score) and well-being (the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's financial well-being score) showed no differences based on gender.

What Differences Do Exist Between How Men and Women Invest?

A few of the attitudes and behaviors we measured, however, were still statistically different when controlling for income.

For example, the overconfidence we so often read about in investor psychology studies may indeed be influenced by gender norms. In every income group of our sample, women were less likely to think of themselves as investors and reported lower confidence in their investment knowledge.

These results echo findings from global studies of financial literacy. In studies of general financial knowledge, women are more likely to answer "I don't know" than men (Bucher-Koenen et. al, 2021). This suggests women guess less frequently, but they also receive lower financial literacy scores: That is, you earn zero points for admitting ignorance but can sometimes eke out a few extra points for guessing correctly.

The greater willingness to admit not knowing hurts women on financial literacy tests, but it may make them ideal clients. The willingness to say "I don't know" suggests humility and openness to learning, which can contribute to a good advisor-client relationship.

Ironically, women were also less likely to have made recent changes to their investments, which could indicate greater investment composure. Gender differences in trading behavior have been found to reduce men's net returns (Barber and Odean, 2001). It seems that, while women have lower confidence in their investment knowledge and abilities, they are also less likely to face the expensive consequences of overconfidence.

From Research to Practice

Our research provides a nuanced view of the common stereotypes regarding women in the finance industry. Put together, we can glean a few takeaways for both financial professionals and women investors.

For women investors:

- Unfortunately, some advisors may continue to overly rely on common stereotypes when working with women investors, and you must be prepared to recognize that and walk away. To ensure your financial needs are being met when working with an advisor, prepare a checklist noting your expectations when working with the advisor and refer to it after the meeting. Ask yourself: Did they address my needs? Or did they bulldoze through some topics during the conversation, making some assumptions along the way?

For financial professionals:

- As our research shows, there are some tendencies that may make women investors unique, generally speaking. However, there are plenty of other misconceptions that don't play out in the data. When working with women investors, lean on your predefined processes--such as an established onboarding process--to make sure you stay on track.

- There are also plenty of resources to bring you up to speed on working with women investors. To get started, check out Andrea Turner Moffitt’s Harness the Power of the Purse: Winning Women Investors.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/6c608d29-bb89-4580-943a-7819645ad538.jpg)

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/e03cab4a-e7c3-42c6-b111-b1fc0cafc84d.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IFAOVZCBUJCJHLXW37DPSNOCHM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GQNJPRNPINBIJGIQBSKECS3VNQ.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/6c608d29-bb89-4580-943a-7819645ad538.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/e03cab4a-e7c3-42c6-b111-b1fc0cafc84d.jpg)