It’s Time to Revisit Social Security’s Early and Delayed Claiming Formulas

The current system dates to the 1950s--and much has changed since then.

When it comes to claiming Social Security, there are a few basic rules of thumb.

A delayed claim gets you more monthly income--in some cases, a lot more. Claiming early, meanwhile, reduces your monthly income. But the delayed credits and early claiming penalties were designed--years ago--to be actuarially fair. In other words, you should get the same total benefit over the course of your lifetime no matter when you file, assuming average longevity.

But is that still the case?

The current formula traces its roots to the mid-1950s, with tweaks along the way. Over the years, the underlying actuarial factors have changed. Interest rates have fallen and life expectancy has risen--the latter, much more so for high earners.

For some, the current delayed credits are too generous. And it’s clear that the reductions for claiming early should be reduced--a change that would be especially helpful for older workers forced into retirement by the coronavirus pandemic.

Before we dive into the details of this idea, let’s review the basics on how Social Security benefits are calculated.

Ready, Set, AIME Calculation of your benefit begins with a calculation of your Average Indexed Monthly Earnings (called the AIME). This formula takes your 35 years of highest wages and indexes them to current wage levels in the economy.

Next, AIME is converted into your Primary Insurance Amount (your PIA). This is a weighted formula that gives a higher benefit relative to career earnings for a lower earner than for a high earner.

From there, the benefit you'll receive revolves around the Full Retirement Age (or FRA)--the age when you can receive 100% of PIA. Currently, the FRA is 66 plus a few months, depending on your year of birth; it is headed to 67 for workers born in 1960 or later under reforms enacted in 1983. The early claiming formula reduces benefits by 6.7% for every 12 months before your FRA and increases payments by about 8% after age 66 for every 12 months up until age 70 (when further credits no longer are available).

Actuarial fairness aside, many retirees wind up receiving a higher lifetime payout from delayed claiming. Waiting one year past FRA gets you 108% of PIA (for life); FRA plus two years gets you 116%. Or, to put it another way--claiming at FRA is worth 33% more in monthly income than a claim at 62, and a claim at age 70 is worth 76% more than a claim at age 62.

This system often can be particularly beneficial for married couples, who can coordinate their claiming. For example, a lower-earning spouse could file either before or at FRA to get some income flowing while the higher-earning spouse delays. Very often, the delayed claimer will be male. Because women tend to outlive men, they can often step up to 100% of a deceased spouse’s benefit as a widow.

What Revisions Make Sense The current structure for varied claiming dates to 1956, when Congress gave women the option to retire as early as 62 with a reduced benefit. The idea was to allow married women to retire and claim at the same time as their (typically older) husbands. But the option was made available to all women, married or not. Early claiming was extended to men in 1961.

Delayed credits were introduced in 1972 and tweaked over the years; the current formula was adopted in the reforms of 1983.

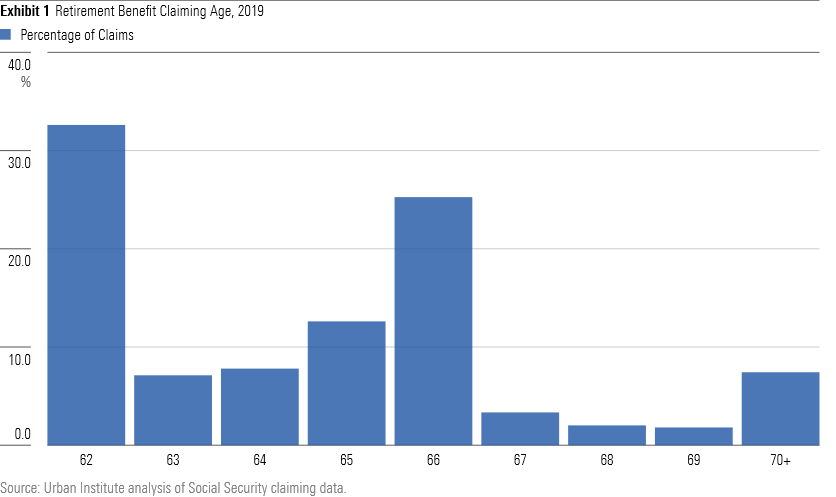

Most people still file for Social Security at or below their FRA. In 2019, 32.6% of retirement benefits were claimed at age 62, according to analysis of Social Security data by the Urban Institute. A full 60% of those eligible to claim benefits file before their FRA, 25.3% claim at their FRA, and just 14.6% claim at age 67 or older.

Early claiming likely will increase due to the pandemic, notes Richard W. Johnson, director of the program on retirement policy at the Urban Institute. The labor force participation rate for workers age 65 or older fell 7.4% between January 2020 and January 2021, much higher than among other age groups.

A study by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College found that the delayed credit is still about right, with the exception of the highest earners, who tend to outlive actuarial averages and reap the highest extra benefit. Conversely, the group hurt the most are low-income filers, who tend to claim earlier and effectively are overcharged for doing so. Moreover, the increase in FRA from 65 to 67, enacted in the reforms of 1983, effectively increased the penalty for earlier files. Claimers with an FRA of 67 will receive five years of early filing reductions rather than three.

Reducing the penalties for early filing would make sense, says Anqi Chen, assistant director of savings research at CRR. “But it’s actually not the most important thing that could be done to reduce inequities,” she adds. “Modernizing the benefit structure would have a much greater impact.”

Numerous Social Security reform plans proposed by Democrats include such modernization. As a candidate, for example, President Joe Biden proposed creation of crediting nonpaid caregivers for time that they spend out of the workforce. These workers often wind up with depressed AIME if they work fewer than 35 years, since nonworking years still count in the “high 35” calculation. Plus, coming in and out of the workforce tends to depress their earning trajectories.

Biden also has proposed expanding benefits for widows and seniors who had collected payments for 20 years, and a more generous yardstick for determining Social Security’s annual cost-of-living adjustment.

How to meet the higher cost of such expansions? This is a critical question, considering that Social Security faces a long-range solvency problem separate from any expansion plans. The combined retirement and disability trust funds are projected to be empty around 2034.

To fund the expansion, Biden has proposed adding a new tier of payroll tax contributions for high earners. Currently, workers and employers split a 12.4% tax, levied this year on incomes up to $142,800; Biden would add a new tax at the same rate on incomes over $400,000. Doing so would extend the trust fund’s solvency by about seven years--far less than the 75-year horizon that Social Security is required by law to forecast. The other option is to gradually increase payroll tax rates, perhaps 1% over a 10-year period.

Some of the higher cost could be offset by reducing benefits for high earners. That could be done by trimming delayed filing credits. For example, CRR found that higher earners are the most likely to file after FRA--49% of those in the fourth income quintile, and 51% of those in the highest quintile, compared with just 40% in the lowest quintile.

Another approach: adjust the “bend points” used to determine PIA. Currently, beneficiaries receive:

- 90% of the first $996 of AIME

- 32% of AIME from $996-$6,002

- 15% of AIME over $6,002

A bend point revision could award less to the two higher-income brackets.

This type of “means testing” might seem reasonable if you buy into the “Warren Buffett doesn’t need Social Security” arguments that we hear from time to time. It’s not debatable that Mr. Buffett could do just fine without a Social Security check--but the argument really is just a distraction.

Even the wealthiest Social Security beneficiaries don’t receive high benefit payments because the program is geared to help everyday workers. The maximum monthly benefit for a worker retiring last year at FRA was $3,011, according to the Social Security Administration. Moreover, there aren’t enough Warren Buffetts in the Social Security system to make a meaningful difference in the program’s finances.

Just as important, reducing benefits for high-income people would tear at the fabric of social insurance: The idea is that we all contribute to programs such as Social Security and Medicare, and we all receive (more or less) the same benefit in return. (That's why I have a problem with Medicare's Income Related Monthly Adjustment Amount--you simply pay more to Medicare and get absolutely nothing in return.)

Lastly, affluent households with longer longevities may ultimately rely on Social Security more than they might think. With traditional defined benefit pensions receding, Social Security will be the only lifetime guaranteed income source for many--and it is adjusted for inflation annually. That annuity-style income can come in very handy at very advanced ages, when savings may be exhausted.

A better approach is to inject new revenue--an idea with broad political support. An AARP poll last year found agreement among Democrats, Republicans, and independents with this statement: "It would be better to pay more into Social Security now to protect benefits for future generations."

Broad agreement among Americans is pretty rare these days. Policymakers would do well to jump at the chance to do something popular.

Mark Miller is a journalist and author who writes about trends in retirement and aging. He is a columnist for Reuters and also contributes to The New York Times and WealthManagement.com. He publishes a weekly newsletter on news and trends in the field at RetirementRevised. The views expressed in this column do not necessarily reflect the views of Morningstar.

Mark Miller is a freelance writer. The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MFL6LHZXFVFYFOAVQBMECBG6RM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HCVXKY35QNVZ4AHAWI2N4JWONA.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EGA35LGTJFBVTDK3OCMQCHW7XQ.png)