Why Investment Complexity Is Not Your Friend

When it comes to investing, keep it simple instead.

Mutual funds were originally meant to make life simple. At a time when it was difficult or impossible for individual investors to assemble a diversified portfolio without paying steep trading commissions, funds such as MFS Massachusetts Investors Trust MITTX, Vanguard Wellington VWELX, and Pioneer Fund PIODX started a brand-new industry in the 1920s, which then became more regulated and transparent with the Investment Company Act of 1940.

Since then, the fund industry has grown into a $20 trillion-plus colossus, with more than 10,000 mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (not including multiple share classes) available for investors in the United States. Such abundance is an embarrassment of riches for the everyday investor, but doesn’t always lead to better results. In this article, I’ll delve into the perils of complexity and suggest a few ways to simplify things instead.

Complexity Abounds

The fund industry now includes a dazzling variety of options, from active to passive, long to short, inverse to leveraged, and various combinations thereof spanning nearly every conceivable asset class, and then some. Morningstar’s U.S. fund database now includes 28,000 share classes from more than 800 different fund companies and 128 categories.

Recent fund launches have become increasingly esoteric and niche-oriented: During the past three years, for example, fund companies rolled out at least 139 funds focusing on options trading, 53 leveraged equity, 39 digital assets (aka cryptocurrency), 26 trading—inverse equity, 274 sector, and 205 thematic funds.

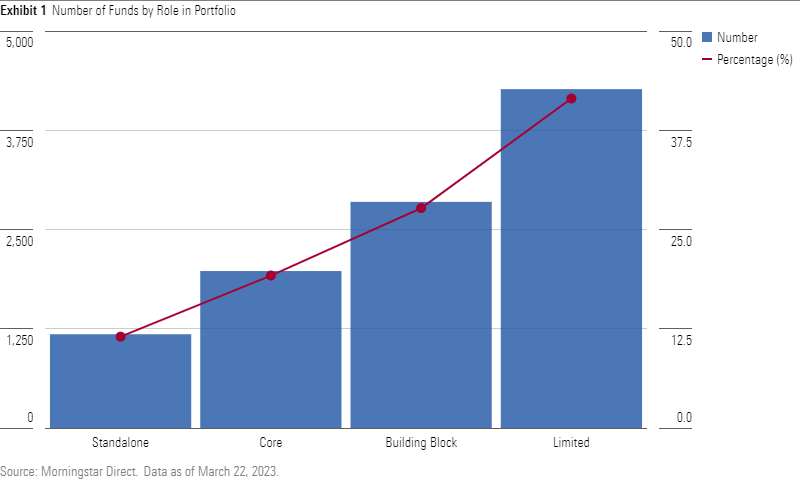

Not only can this range of options be overwhelming, but it often leads to worse investor outcomes. As I wrote about a few weeks ago, Morningstar recently introduced a new Role in Portfolio framework designed to help beginning investors simplify the investment process and avoid big portfolio mistakes. One key dimension of this framework focuses on maximum position size—that is, the percentage of assets that we recommend devoting to a given type of fund within a portfolio. We divide the fund coverage into four main groupings: stand-alone (which can occupy as much as 80% to 100% of a portfolio), core (40% to 80%), building block (15% to 40%), and limited (less than 15%).

We found that nearly half of all mutual funds and ETFs currently available land in the limited role. In other words, many of the funds that investors encounter should only play a small role in their portfolios—if any role at all. Stand-alone funds—which are more suitable for most or all of an investor’s portfolio because of their built-in asset class diversification—only account for about 14% of available offerings. Core holdings, meanwhile, make up less than one fourth of the fund coverage.

Why Complexity Doesn’t Help Investors

This topsy-turvy state of affairs hasn’t led to better results for investors. In fact, there’s ample evidence that fund companies are prone to rolling out highly specialized offerings at exactly the wrong time: after a given sector has already attracted investor interest, leading to higher valuations and risk levels. Cryptocurrency is a case in point. Interest in the area exploded in the wake of the area’s tenfold runup from 2019 through 2021. The number of fund offerings focusing on digital assets went from about two to about 30 by the end of 2021. That was just in time for the sharp correction in 2022, when the CMBI Bitcoin Index lost close to two thirds of its value.

Similarly, nearly 70 new technology funds came out between 2019 and 2021, attracting more inflows than any other sector-fund category. After posting cumulative returns of about 142% over that three-year period, funds in the technology category dropped about 38%, on average, during the 2022 bear market.

This pattern has led to a persistent gap between the returns investors actually experience (also known as investor returns or asset-weighted returns) and reported total returns. This gap has averaged about 1.7 percentage points across all fund categories over the 10-year period ending in 2021.

On a more practical note, complexity increases the number of details for investors to keep track of. More accounts mean more passwords to remember, more account statements to gather up at tax time, more time spent on rebalancing, and more accounts to tally up for required minimum distributions. Life is complicated enough without adding scores of portfolio holdings to the mix.

Cutting Through the Gordian Knot of Investment Complexity

There are a few ways to avoid investment complexity. One of the most helpful tactics is to tune out the day-to-day noise of economic and market news. Particularly during volatile and uncertain times, there’s almost always something worrisome or panic-inducing happening, but making drastic portfolio moves in response is usually a bad idea. On a related note, don’t be afraid to put things on your “too hard” pile. Complicated investment products or strategies that you don’t understand usually won’t lead to better results. And if something sounds too good to be true (a higher-than-average yield, triple-digit returns, a manager who promises to perform well no matter what the market environment), it’s usually a red flag.

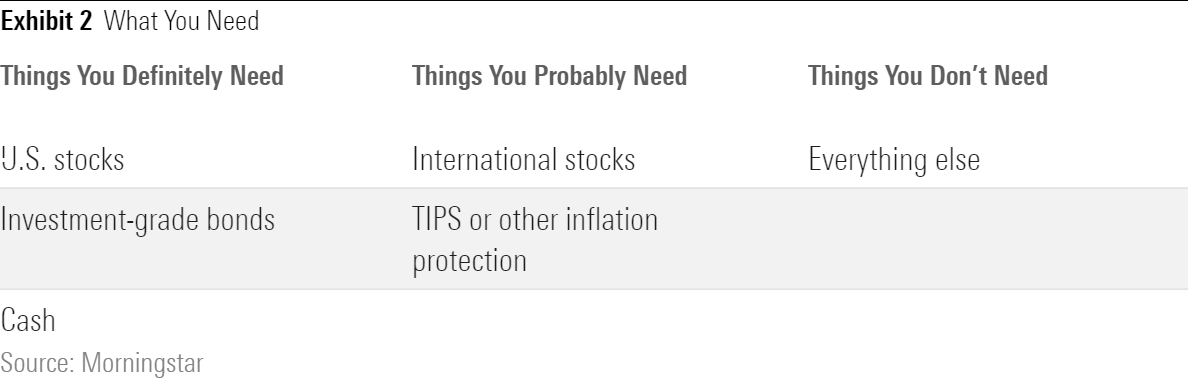

Instead, be a ruthless editor of your investment life. There are only a handful of asset classes that most investors need, as shown in the table below. Everything else is optional.

For tax-deferred accounts, you can simplify things even more by investing in a target-date fund. These funds offer built-in asset class diversification and automatically adjust their asset mix to become more conservative over time.

Robo-advisors can also be a good option for investors who don’t want to manage their own portfolios. These programs typically start by asking a series of questions to assess an individual’s time horizon and risk tolerance, and then match them up with a suitable portfolio, typically made up of low-cost ETFs.

Ultimately, the most important thing is to focus as intensely as possible on what matters most. An investor who gets a handful of key decisions right—keeping expenses low, saving early and often, and matching her personal time horizon with the right types of funds—will likely fare better than those who get tripped up by complexity.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MNPB4CP64NCNLA3MTELE3ISLRY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/SIEYCNPDTNDRTJFNF6DJZ32HOI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZHTKX3QAYCHPXKWRA6SEOUGCK4.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)