Are You Leaving Money on the Table From Your Funds’ Returns?

The gap between reported total returns and actual results may seem daunting, but investors can take steps to minimize it.

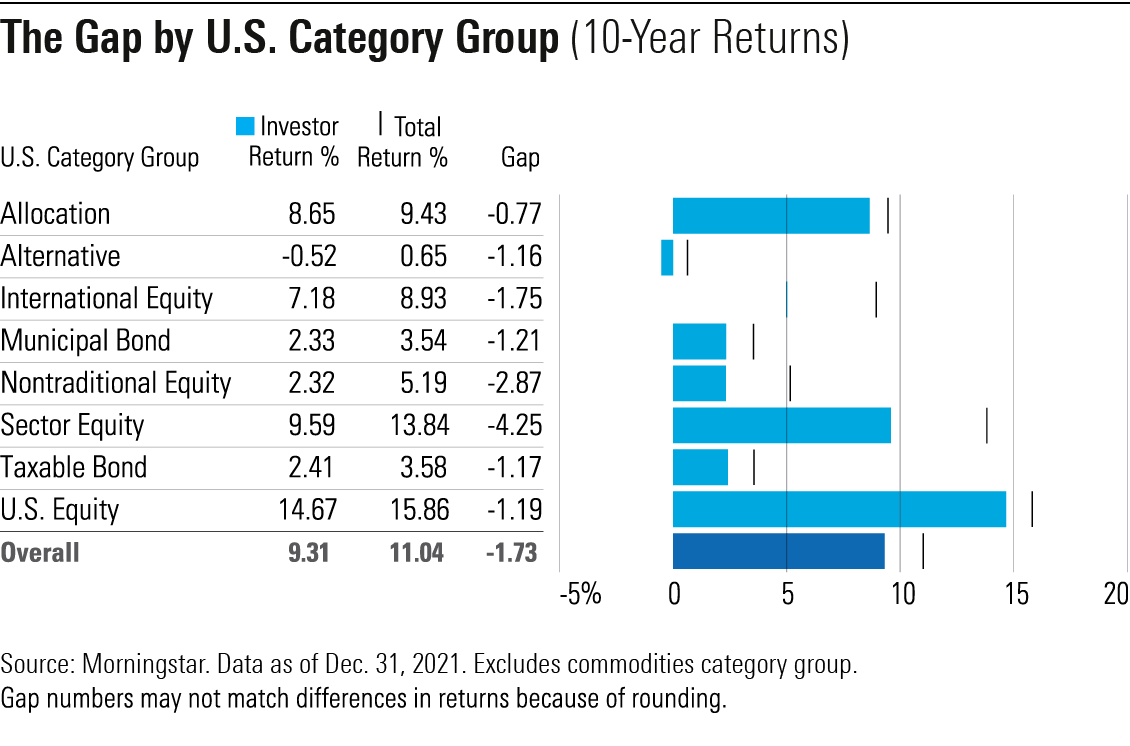

Our annual “Mind the Gap” study of dollar-weighted returns (also known as investor returns) finds investors earned about 9.3% per year on the average dollar they invested in mutual funds and exchange-traded funds over the 10 years ended Dec. 31, 2021. This was about 1.7 percentage points less than the total returns their fund investments generated over that span. This shortfall, or “gap,” stems from poorly timed purchases and sales of fund shares, which cost investors nearly one sixth the return they would have earned if they had simply bought and held.

The persistent gap between the returns investors actually experience and reported total returns makes cash flow timing one of the most significant factors—along with investment costs and tax efficiency—that can influence an investor's end results. But there are a few steps investors can take to improve their results.

1. Focus on holding a small number of widely diversified funds.

As the fund industry has grown, asset-management firms have rolled out more and more highly specialized funds. Theme-based sector funds, alternative funds of various stripes, leveraged factor portfolios, and single-country funds are just a few examples. But investors have fared far better by keeping things simple and sticking with plain-vanilla, broadly diversified funds. More broadly defined offerings, such as U.S. equity and taxable-bond funds, have fared significantly better than narrower offerings, such as sector funds and alternatives.

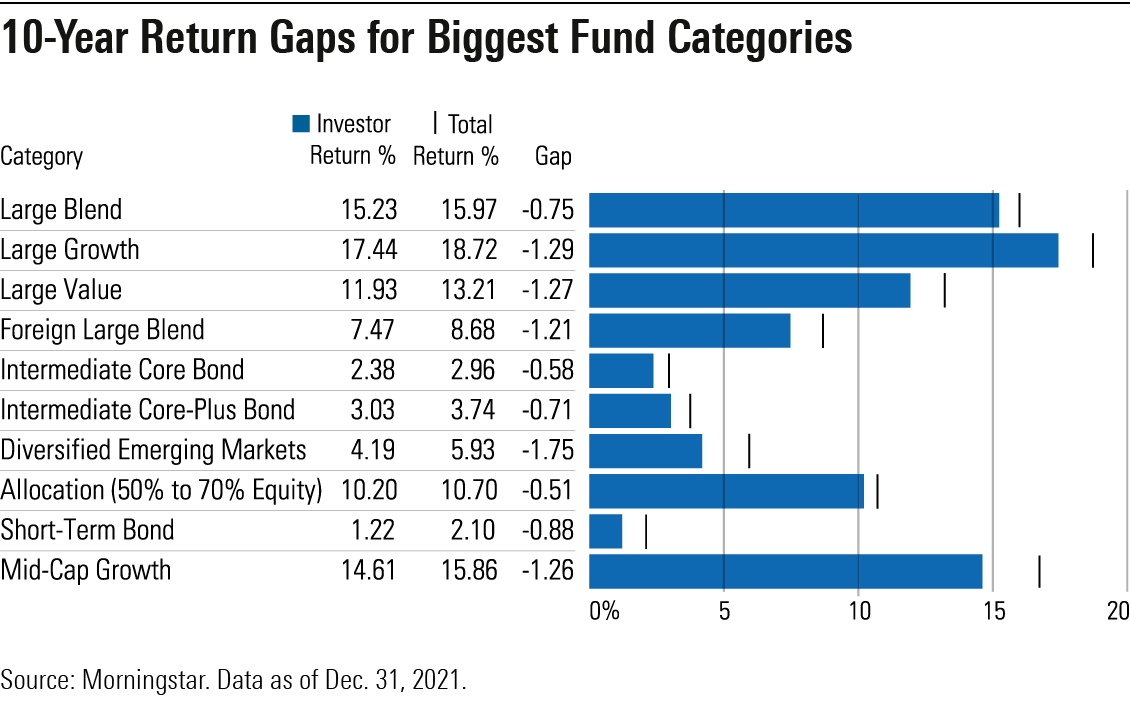

Simpler has also been better when it comes to specific Morningstar Categories. The broadest categories, such as large blend, intermediate core bond, and foreign large blend, have generally fared better than more narrowly defined categories (partly because their large asset bases tend to buffer the impact of net inflows and outflows). From a portfolio-construction perspective, that means investors should lean heavily on these areas as core holdings and avoid narrowly defined funds that tend to have the widest return gaps.

Funds that offer built-in asset-class diversification also excelled in our study. Morningstar has often sung the praises of target-date funds, which provide a preset blend of exposure to major asset classes that shifts over time. These funds and other asset-allocation offerings, such as balanced funds, have consistently shown some of the smallest investor-return gaps. Not only are these funds easy to use, but they're also easy to live with. Investors tend to buy and hold them for long periods, or make investments on a regular schedule that enforces investment discipline and helps them avoid the temptations—and pitfalls—of trading at the wrong time.

2. Avoid narrow or highly volatile funds.

As a corollary to focusing on broadly diversified funds, it's also important to avoid highly specialized or volatile offerings. Sector funds, for example, have been difficult for investors to use effectively. Not only did the average sector fund trail the broader market by a wide margin, but dollar-weighted returns for this category group were more than 4 percentage points lower than reported total returns. (Investor returns for thematic funds that focus on a specific niche within a given sector have been even worse.)

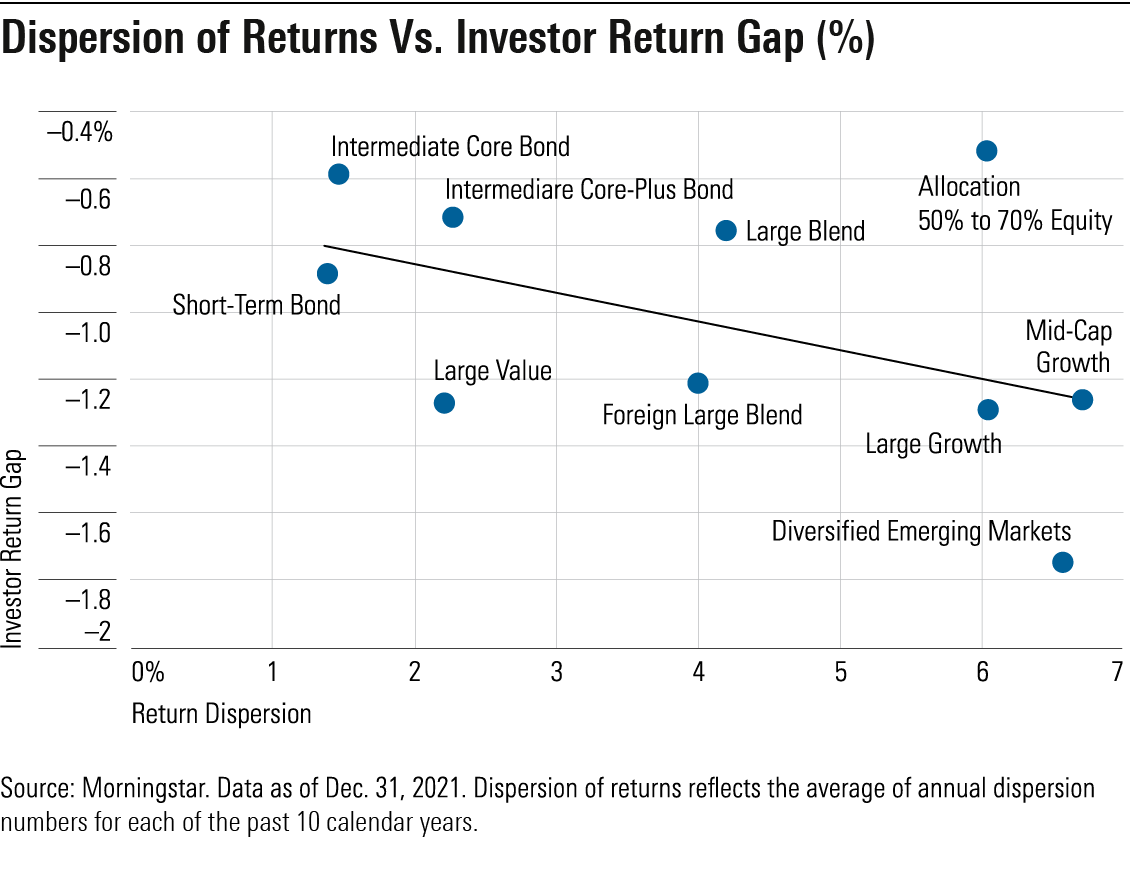

In addition to month-to-month volatility for specific funds, we also looked at the dispersion of returns within categories, which measures the range of returns across individual funds. We found that not only are the most-volatile funds difficult to use well, but varied fund returns within the same category likely make it more difficult for investors to use funds effectively, as opposed to categories with a narrow range of returns. With only a few exceptions, funds that expose investors to less volatility and less dispersion of returns are easier to own and less prone to erratic cash flows.

3. Automate routine tasks, such as setting asset-allocation targets and periodically rebalancing.

Investors can easily get caught in a cycle of analysis paralysis by fretting over how much to buy or sell at various times. The endless drumbeat of market and economic news can make it tempting—even for professional investors and financial advisors—to feel like they should be doing something to respond to shifting market conditions. But for the most part, the time and energy that investors spend on trading decisions is wasted effort—and often counterproductive. Investors can improve their results by setting a rational asset allocation, buying low-cost funds, and just sticking with the plan. It also makes sense to set a strict schedule for rebalancing, such as rebalancing once per year or when your portfolio's allocations drift significantly away from target levels.

4. Embrace techniques that put investment decisions on autopilot, such as dollar-cost averaging.

Dollar-cost averaging often gets a bad rap because it creates a drag on returns when market returns are generally positive. Investors who have a lump sum available will usually earn better results by putting it all to work as soon as possible instead of investing it gradually over time (which means keeping some assets on the sidelines). Investors who have the means—and the temperament—to buy and hold over the long term will likely enjoy the best results.

But successful lump-sum investing depends on two key things: 1) having money available to invest all at once, and 2) having enough discipline to buy and hold despite the vagaries of the market. Unless they're fortunate enough to have large sums of money available via inherited wealth or other windfalls, most investors can only invest a little at a time as money becomes available—for example, setting aside a certain percentage of each paycheck to invest for retirement. This approach isn't technically considered dollar-cost averaging, but it has the same effect because it involves making systematic investments over time.

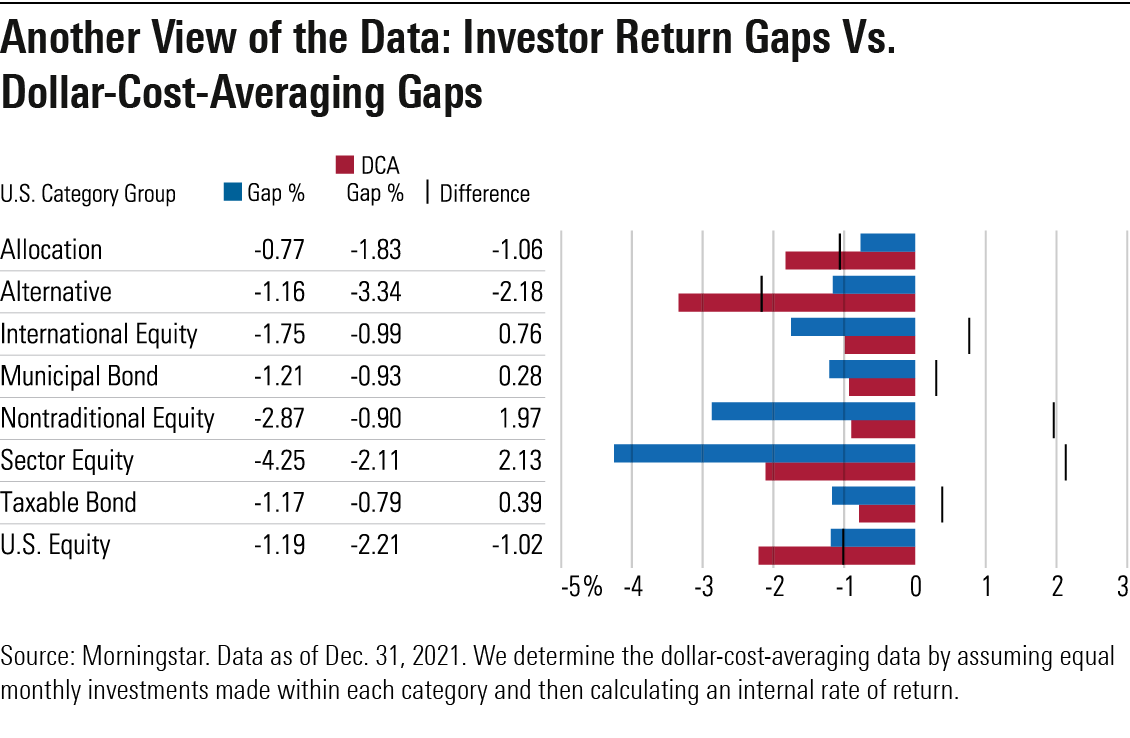

Our study suggests that this approach can significantly improve investors' results, particularly in category groups that are more difficult to use effectively. While systematic investing may not be ideal compared with buy-and-hold investing, it can still improve investors' actual results because it helps them avoid the pitfalls of poorly timed inflows and outflows.

Saraja Samant contributed to this article.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/YGF5R6YDPJESJOU7XABKHHIP3Q.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BNHBFLSEHBBGBEEQAWGAG6FHLQ.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)