2 Ways to Avoid Big Portfolio Mistakes

New guidelines to help investors build effective portfolios.

Individual investors have more investment options than ever before—which means it’s harder than ever to design an effective portfolio.

Even after deciding to limit investments to mutual funds and exchange-traded funds, a U.S.-based investor faces more than 10,000 different funds (not including multiple share classes) spanning roughly 130 Morningstar Categories. And after deciding that a specific fund has merit, an investor must still figure out the specific role it should play in their portfolio, specifically how it aligns with a given time horizon, and what percentage to allocate to it.

As a result, investors often struggle with putting investment decisions into practice. Many people accumulate holdings over time, and the percentage allocated to each one may or may not be a good fit for their time horizon and investment goals. Indeed, while most investors need to invest for long-term goals such as retirement, data on redemption rates from the Investment Company Institute suggests the average holding period for mutual funds is relatively short (between four and five years).

Morningstar has also found a persistent gap of about 1.7 percentage points per year, on average, between reported total returns and the asset-weighted returns investors actually experience. Both of these things suggest that many investors aren’t using funds as effectively as they could.

Morningstar’s new Role in Portfolio framework, which we describe in more detail in a recently published paper, is designed to remedy this problem.

Two Key Dimensions for Assessing a Fund’s Role in a Portfolio

Investors planning to purchase a specific fund should consider two key questions that likely align with how they think about their goals:

- What is the appropriate time horizon, or holding period?

- What percentage of my portfolio should I allocate to this fund?

Getting these two questions right can go a long way toward improving investors’ results and helping them avoid major mistakes. In both cases, the goal is to provide general guidance for how a given fund might be used effectively.

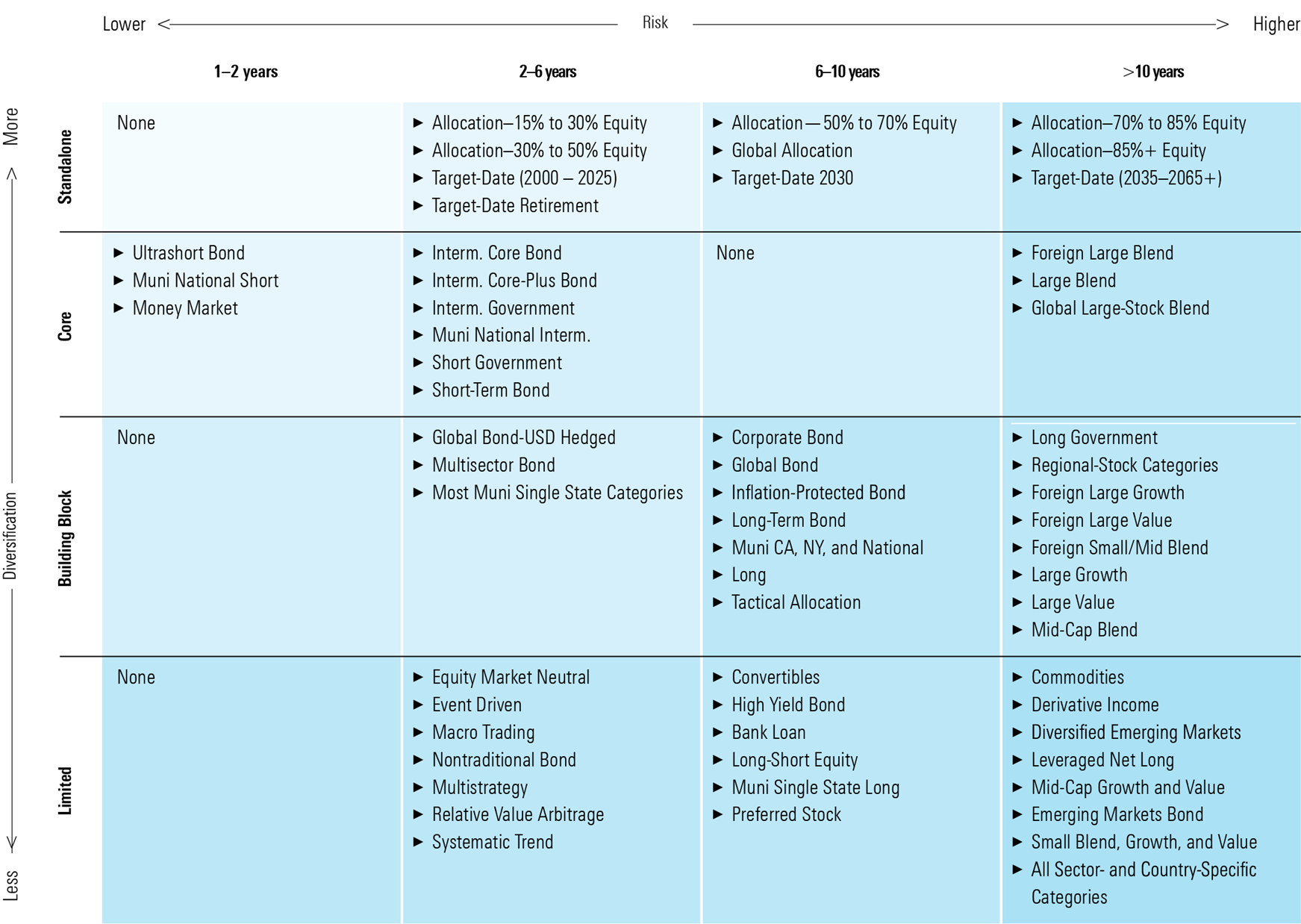

To develop this framework, we used Morningstar’s category classification system as a starting point. In practice, the Morningstar Categories generally reflect major asset classes and sub-asset classes, and typically explain a large amount of the variation in performance and risk across funds. We then classified each category based on two key dimensions: a recommended minimum holding period and a maximum position size within a portfolio.

What is the Appropriate Time Horizon for Holding a Fund?

Although academic finance traditionally defines risk as volatility (or standard deviation), the real risk investors face is that of not having enough assets available to meet their goals. Matching the recommended minimum holding period with the expected time horizon can reduce this risk.

For example:

- Riskier assets, such as stocks, are a better fit for long-term goals because they’re more likely to generate losses in the short term but have better growth potential over longer periods.

- Safer assets, such as short-term bonds, are a good fit for near-term funding needs, but not likely to generate high-enough returns to support funding for long-term goals.

To help investors match their expected time horizon with the most appropriate funds, we divided the category universe into four broad groupings: 1-2 years, 2-6 years, 6-10 years, and greater than 10 years.

What Percentage of My Portfolio Should I Allocate to This Fund?

This is another major question that investors face when determining how an investment fits into their portfolios: How large a position should it be as a percentage of the whole?

Investors often spend more time thinking about whether a fund is worth buying than they do about how to use it—that is to say, how much space it should occupy within a portfolio. They then might end up with a large assortment of funds, with each one occupying a different percentage of assets depending on when it was purchased and how well it performed since that date. This can lead to disastrous consequences at times: For example, during 2022′s bear market, portfolios that were overweighted in growth-heavy funds or technology stocks fared significantly worse than more balanced portfolios.

To address this issue, we divided the category universe into four additional groupings based on a recommended maximum position size: main/stand-alone (80% to 100% of assets); core (40% to 80% of assets); building block (15% to 40%); and limited (up to 15%).

The size of each bucket spans a wide range, which gives investors and financial advisors significant leeway to fine-tune the percentage weighting for a given fund. We also tried to set the thresholds with a view toward how practitioners allocate assets in practice.

How the Framework Works in Practice

With four potential options for each component, we end up with a total of 16 potential roles for a given category. The grid below shows where some of the larger Morningstar Categories based on asset size land in the framework.

A few key observations from the image above:

- Mutual funds and ETFs may not be the best fit for short-term needs. You’ll note a few squares in the grid that don’t include any Morningstar Category assignments—notably, the one- to two-year range for most role groupings. The majority of mutual funds and ETFs are geared toward long-term investors, so investors targeting short-term spending needs may want to use other investment types, such as certificates of deposit, bank savings accounts, or Treasury bills, which can be purchased either through TreasuryDirect.gov or through many brokerage platforms.

- Many funds are only appropriate for a small percentage of a portfolio with a long-term time horizon. The grid also offers some insight into the relative risk levels and diversification of different Morningstar Categories. The level of risk generally increases in boxes further to the right, while diversification decreases in boxes moving lower in the grid. In our framework, however, a disproportionate number of fund categories land in the bottom right-hand square, which we would recommend be used only as a small percentage of assets for investors with a long-term time horizon. Close to one third of fund categories in the U.S. have limited role designations along with a recommended time horizon of at least 10 years. In other words, a large percentage of fund offerings available have limited utility for investors trying to build diversified portfolios, which probably explains why investors often struggle to use funds effectively.

- The role in portfolio assignments underscore the importance of broad portfolio diversification. For most investors, asset class diversification is the primary goal of portfolio construction. As a result, the only fund categories that we classify as stand-alone holdings are those that are broadly diversified across asset classes, such as most of Morningstar’s allocation and target-date categories. Because of their built-in diversification, we consider these funds suitable as either the main holding in a portfolio (consuming 80%-100% of assets) or as the only holding in a portfolio. More specialized fund types, on the other hand, should generally make up a smaller percentage of assets.

The Value of the Role in Portfolio Framework

For decades, institutional investors have relied on Modern Portfolio Theory to construct portfolios, with the goal of maximizing returns for a given level of risk or minimizing risk for a given level of returns. But the reality that individual investors and financial advisors live in is far messier. Most investors have multiple goals, and each goal has a different time horizon and a different level of importance to the investor as an individual. And while investors might find volatility unpleasant, the real risk they face is not having enough assets available to meet their goals.

To address this challenge, the Role in Portfolio framework is designed to help individual investors avoid unforced errors—portfolio mistakes that can have permanent negative consequences. As the investment world becomes increasingly complex, investors can often improve their outcomes by getting a handful of key decisions right: keeping expenses low, matching the time horizon for their specific goals with appropriate portfolio holdings, and avoiding outsize bets on riskier asset classes. The Role in Portfolio framework aims to simplify investment decision-making and improve investor outcomes.

Jimmy Cheng, Scott Thompson, and Jeff Ptak contributed to this article.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/URSWZ2VN4JCXXALUUYEFYMOBIE.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/CGEMAKSOGVCKBCSH32YM7X5FWI.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)