How Rising Interest Rates Affect Your Retirement Plan

Be aware of implications for returns, withdrawal rates, and asset allocation.

The “Magnificent Seven,” cryptocurrency, and artificial intelligence have captured investors’ attention over the past few years. But another force is all but a lock to shape investors’ portfolios and financial plans for the next decade or more: rising interest rates.

Higher yields have particularly dramatic implications for people who are getting close to or are in retirement for a simple reason: Their portfolios generally have more exposure to interest-producing investments like cash and bonds than is the case for younger investors. By boosting return prospects for the “safe” portion of portfolios, higher yields make every other aspect of retirement planning easier. Asset allocations can reasonably be more conservative and starting safe withdrawal rates can be higher. All of those developments are positives for people embarking upon or already in retirement. This week, I’ll discuss the portfolio-related effects of rising rates; next week I’ll discuss nonportfolio considerations.

Higher Yields: Recent History

While investors had to make do on ultralow yields in the decade-plus coming out of the global financial crisis, the upward turn in interest rates has been jarring. The Federal Reserve held its target federal-funds rate at 0 in the first quarter of 2022. By the end of 2023, that target had increased to a range of 5.25% to 5.50%.

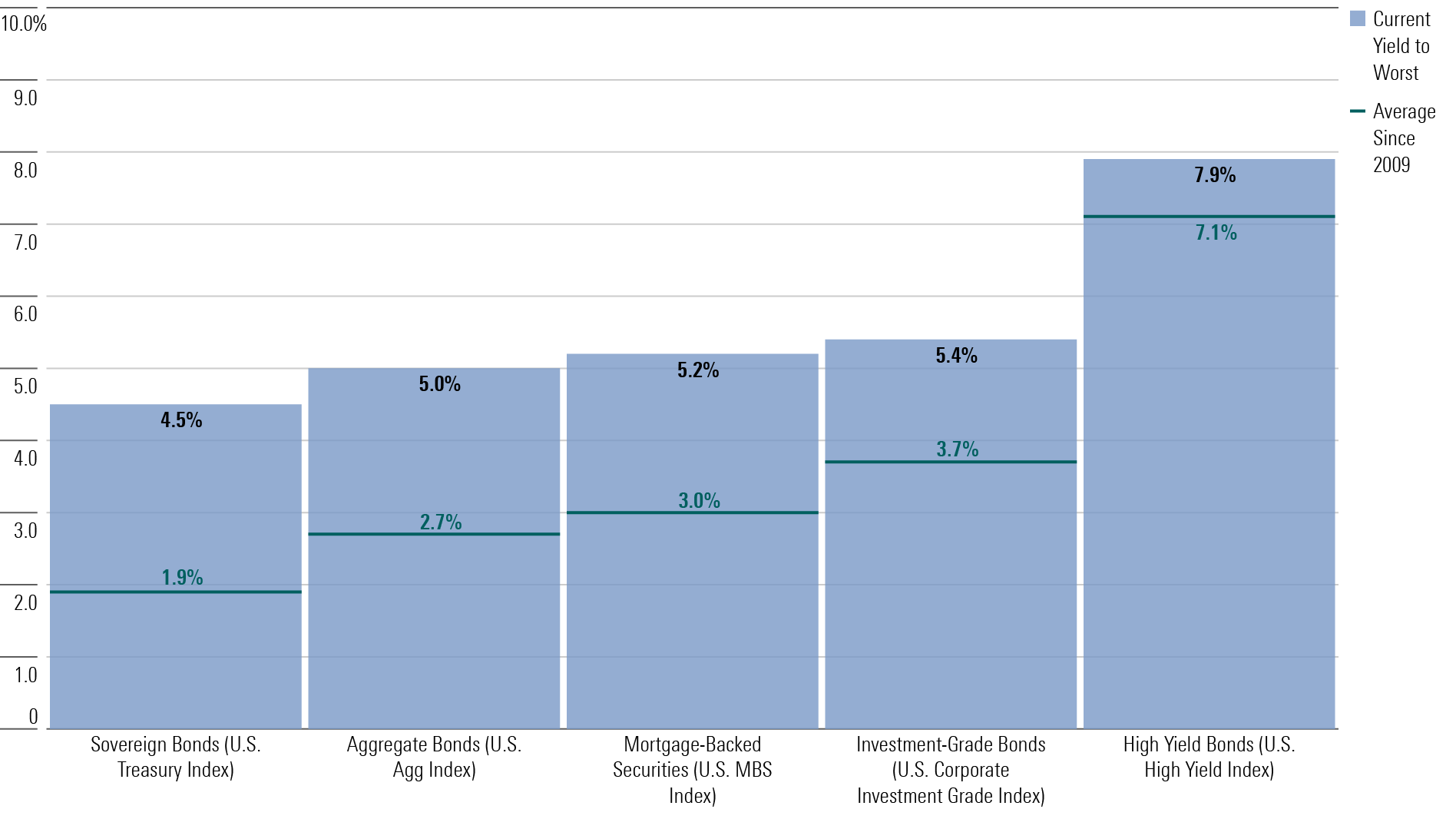

The chart below depicts just how high yields for various slices of the bond market are relative to their averages over the past 15 years since the global financial crisis. The escalation in yields on high-quality bonds—government-issued (sovereign) bonds as well as the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index—has been especially sharp relative to their 15-year average.

Bond Yields Are Very Attractive Relative to Recent History

Of course, higher rates are a negative for bond investors in the short term, simply because the availability of new, higher-yielding bonds depresses the value of similar bonds with lower yields. High-quality, long-duration bonds tend to be especially vulnerable when rates move up. First, they’re highly liquid and have limited credit risk, so they’re more sensitive to changes in interest rates than bonds where credit risk and other factors affect the attractiveness of the bonds. Moreover, an investor in a long-duration bond has to settle for a lower yield for a longer period. For example, long-term Treasury bond funds lost roughly 29% in 2022. Intermediate-term Treasury funds lost about 11%, and the Aggregate Index lost about 13%. Meanwhile, short-term bond funds lost just 5% in 2022.

Implications for Future Returns

Despite bonds’ price dislocation in 2022, higher yields set fixed-income securities and cash up for higher future returns. That’s because for bond investors, yield is by far the biggest component of the return you earn. And for cash investors, yield is the only return you earn, because there’s no potential for appreciation in cash holdings.

Our Morningstar research on retirement income depicts how cash and bond yields have increased 30-year return prospects for these asset classes versus 2021.

| Investment Type | 2021 (%) | 2023 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. Investment-Grade Bonds | 3.50 | 4.93 |

| Foreign Bonds | 3.30 | 5.15 |

| Cash | 1.71 | 3.31 |

Source: Morningstar Investment Management.

While most investment managers don’t publicize capital markets assumptions for a 30-year period, there’s a solid consensus about the connection between today’s higher yields and higher future returns, at least over the next decade. In my most recent roundup of expert forecasts, most firms were expecting 10-year bond returns to fall between 4% and 6%. That stands in contrast to forecasts in 2021 when yields were significantly lower and most firms were forecasting 10-year high-quality bond returns of 2% or less.

Implications for In-Retirement Withdrawal Rates

Those higher returns aren’t just a theoretical benefit for retirees; they also translate into the prospect of higher paydays throughout retirement. In the 2023 research that Amy Arnott, John Rekenthaler, and I conducted on safe starting withdrawal percentages, we concluded that thanks to higher yields (as well as tapering inflation), retirees with balanced portfolios can take a higher starting withdrawal percentage of 4.0%—with the starting amount adjusted thereafter for inflation—and still maintain a 90% probability of not running out of funds over a 30-year horizon. When we conducted the same research in 2022, the safe starting withdrawal rate was 3.8%, and it was 3.3% in 2021. Interest-rate changes aren’t the sole factor behind the higher starting safe withdrawal percentages—equity return prospects and inflation are also in the mix—but they are a key variable.

Implications for In-Retirement Asset Allocations

Relatedly, higher yields should affect how retirees think about their in-retirement asset allocations. One of the most striking aspects of our 2023 retirement income research was that the highest starting safe withdrawal percentage over a 30-year period corresponded with portfolios that had between 20% and 40% in stocks and the remainder in cash and bonds. Over shorter time horizons, the highest starting withdrawal percentages corresponded with even lower equity weightings. Over a 15-year horizon, for example, the highest starting safe withdrawal percentages corresponded with equity weightings of between 10% and 30%.

Those conservative asset-allocation recommendations are a function of the higher yields on offer from cash and bonds today, combined with the very conservative spending system that we use as our “base case” for the research. We assume that a retiree wants a stable inflation-adjusted “paycheck” for a 30-year period and is unwilling to vary those paydays based on portfolio performance or any other factor. Given that spending profile, the Monte Carlo simulations that we use gravitate to a more conservative asset mix. They’re effectively saying that if someone has such a short time horizon, they’re better off locking down a big share of their expected withdrawals in very safe assets at today’s higher yields.

But that’s not to suggest that all new retirees should employ such a conservative spending pattern or asset allocation. In our research, we modeled a variety of dynamic spending systems, most of which vary withdrawals based on portfolio performance. For example, for retirees using a “guardrails”-type spending system that varies annual withdrawals based on how the portfolio behaved in the year prior, the highest starting withdrawal percentage of 5.5% corresponded with portfolios with between 60% and 70% in equities.

And it’s also important to note that not all retirees are hyperfocused on wringing the highest possible withdrawals from their portfolios. For retirees who are bequest-minded, higher equity allocations are closely linked to larger balances after 30 years. For a retiree using a fixed real withdrawal system for portfolio withdrawals (starting annual dollar amount adjusted thereafter for inflation), higher equity positions tended to contribute to substantially higher leftover balances at the end of 30 years. Effectively, a more bond-heavy portfolio might be safer in terms of delivering stable cash flows, but holding more equities provides more opportunities for “upside surprises” in terms of growing the portfolio balance through retirement.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/66112c3a-1edc-4f2a-ad8e-317f22d64dd3.jpg)

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/96c6c90b-a081-4567-8cc7-ba1a8af090d1.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/URSWZ2VN4JCXXALUUYEFYMOBIE.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/CGEMAKSOGVCKBCSH32YM7X5FWI.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/66112c3a-1edc-4f2a-ad8e-317f22d64dd3.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/96c6c90b-a081-4567-8cc7-ba1a8af090d1.jpg)