A Retiree’s Guide to Guaranteed Income

We compare Social Security, TIPS, annuities, and more.

From the Beginning

Six weeks ago, I developed a new hobby: Researching investments that supply guaranteed income. (Technically, in addition to providing income, some of these investments also return capital, so I should have used another term. But every other phrase looks strange. Guaranteed payments? Guaranteed distributions? I cannot use those in a headline.)

Before then, considerations of guaranteed income had barely crossed my mind. I was trained as a mutual fund analyst, and funds provide no guarantees. However, not every old dog avoids new tricks. Indeed, I have quite enjoyed the task, publishing first a comparison between Treasury bonds and immediate lifetime annuities, and three weeks later an article on how to build a TIPS ladder.

All fine and good—but I started my investigation in the wrong place. Before presenting the details, I should have outlined the field. What are the main sources of guaranteed income for U.S. investors? And how do they compare?

Social Security and Pensions

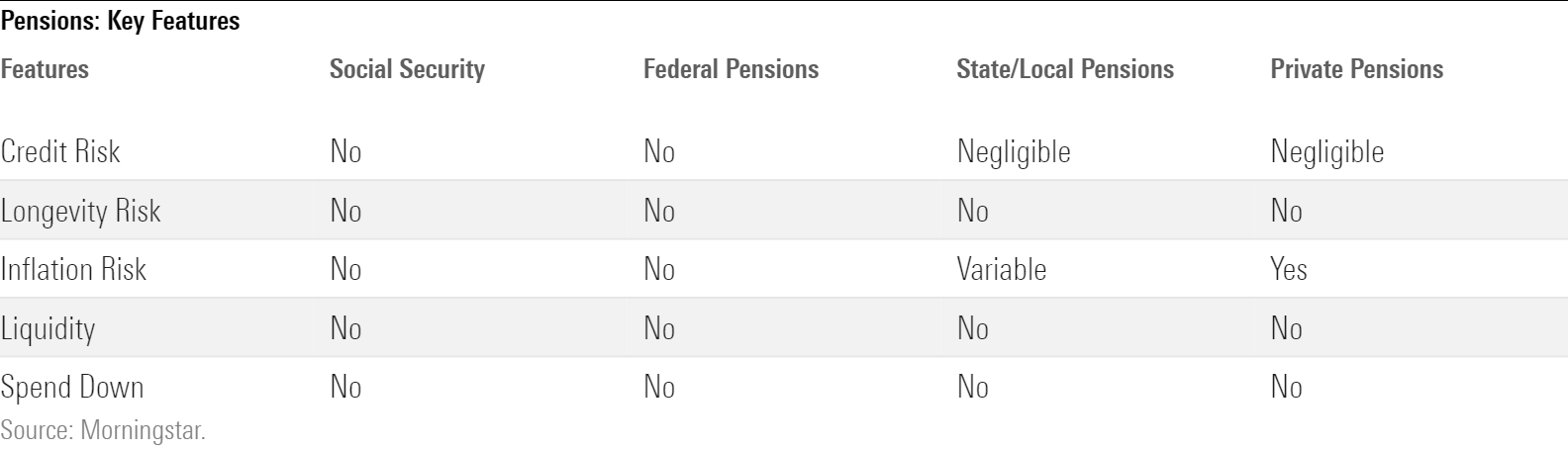

Social Security is income’s gold standard. In truth, it is better than gold, but you understand the analogy. Social Security payments are 1) backed by the United States government, 2) adjusted for inflation, and 3) never expire. All other forms of guaranteed income offer at least one of those advantages, and several boast two, but only Social Security and its sibling, federal pensions, deliver all three.

State and local government pensions aren’t far off the mark. Their sponsors do not possess the federal government’s ability to print money, so their promises could be moot. In practice, though, when government officials cut pension benefits, they typically do so for future retirees, rather than current recipients. Most state and local pensions provide cost-of-living increases, but not all.

At the bottom of the pension list are plans from private companies. Those from larger organizations are typically insured by the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, but should bankruptcy occur, the PBGC’s coverage does not always make recipients entirely whole. A larger problem yet is their lack of inflation protection. Private-sector pensions rarely include inflation adjustments—a policy that could perhaps be tolerated when annual inflation was 2% but which quickly becomes disastrous at a 7% rate.

The table below summarizes the key features of Social Security and pensions. (For three of the rows, the answers are the same for all, but that will not be the case in the next section.)

Personal Investments

On to the more interesting subject of personal investments. By my count, the major candidates consist either of Treasuries (or other securities that are backed by the federal government, for which the same analysis applies) or of annuities from a top-rated insurer. One could dispute the latter since insurance companies sometimes declare bankruptcy, but should that event occur, state agencies offer some protection. (Besides, this is my article, and I wish to include them.)

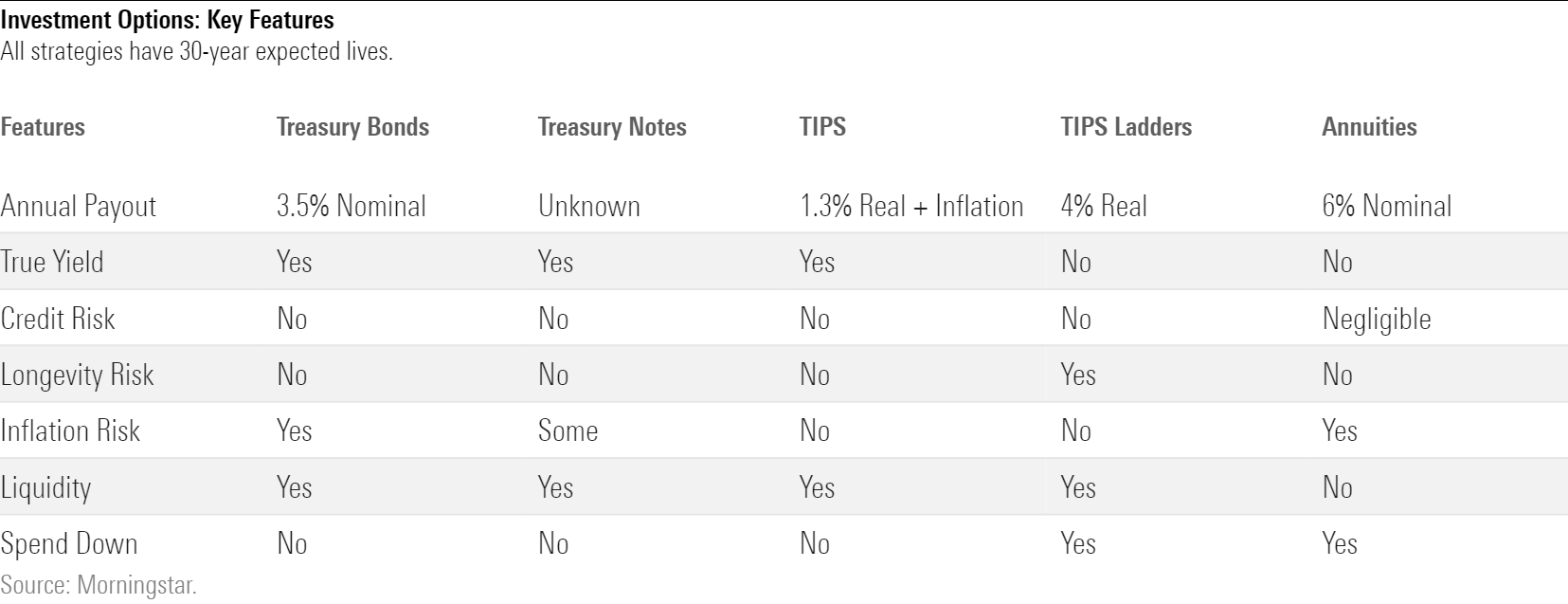

There are five primary strategies:

1) Treasury bonds. Buy and hold a 30-year bond.

2) Treasury notes. Buy, hold, and repurchase five-year notes.

3) Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities. Buy and hold a 30-year TIPS.

4) TIPS ladders. Create a 30-year TIPS ladder.

5) Annuities. Buy an immediate annuity (which is often called a SPIA).

(To be sure, there are many other flavors of annuities, but some are merely variations on the theme, and the rest lie outside the scope of this column.)

Here is how each investment scores. The criteria are the same as in the first table but with two additional rows: 1) their current annual payouts and 2) whether those payouts consist solely of income, or whether they also include capital.

About the Scores

To explain the results:

Annual Payout

None of these figures are directly comparable! The distributions from TIPS and TIPS ladders are calculated in real terms, while those of Treasury bonds and annuities are nominal. Apples and oranges, as the saying goes. Moreover, the two versions of bonds each distribute true yields, while the ladders and annuities do not. Finally, the Treasury-note payment schedule cannot be known, as the yields for five-year Treasuries that will be purchased in the future have not yet been set.

True Yield

We have addressed this issue already. TIPS ladders and annuities have much higher payouts than the other investment options because they supplement their income by returning capital. Determining whether their “income” exceeds that of securities that retain their principal therefore becomes a laborious task. Bad news for investors, although a boon for internet bloggers who need research topics.

Credit Risk

Treasuries carry no credit risk, while annuities do. For the top-rated insurers, that prospect is unlikely. But as it does exist, the threat must be considered. (Note: The 6% payout that I cite is a representative figure from creditworthy insurers for a single person who has a median remaining life expectancy of 30 years.)

Longevity Risk

Longevity risk is the danger of outliving one’s assets. Among the five strategies, only TIPS ladders face that possibility. They are built with a specified life span, and when that life span is complete, their monies are spent. In contrast, the three bond/note strategies repay their initial principal in full, so that it may be reinvested into new securities. And lifetime annuities, by definition, pay as long as the recipient survives.

Inflation Risk

Although in theory annuities can be outfitted with cost-of-living adjustments, in practice almost all are sold without them. Thus, the only listed strategies that combat the risk that high inflation will sharply erode the investor’s purchasing power are the two that contain TIPS.

Liquidity

The one advantage that investments hold over Social Security is that the former can be discarded. Should their owners decide, for any reason, to take another investment path, Treasuries may readily be sold. The same, of course, cannot be said about either Social Security or pensions. Nor can annuities be revoked. Their purchases are final.

Spend Down

This is the flip side of True Yield. TIPS ladders and annuities are designed to spend down the investor’s capital. (With ladders, the math is exact. With annuities, it is not. Buyers receive less than they paid for if they die before their actuarial expectations, and more than they bargain for if they die later.) In contrast, the other three strategies repay the investor’s principal.

This column was originally published on Dec. 15, 2022. Since that time, the annual payout amounts cited in the “Investment Options: Key Features” column have increased for each of the cited investments.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WDFTRL6URNGHXPS3HJKPTTEHHU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IFAOVZCBUJCJHLXW37DPSNOCHM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)