How to Build a TIPS Ladder

But are today’s prices right?

A Rare Breed

Social Security payments reliably safeguard against inflation. Critics sometimes dispute the details of the administration’s cost-of-living adjustments—although, one suspects, few recipients will complain about next year’s 8.7% increase—but in the grand scheme of things, such objections are pebbles on the beach. Social Security does what the label promises: provide steady, inflation-proofed income.

After that … pfft. Traditional investments sometimes thrive during high inflation, as with energy stocks this year, but they offer no guarantees. For their part, almost all annuity payments from insurance companies are nominal rather than real. The sole investments that consistently repel inflation are Series I Savings Bonds, or I Bonds, but as they can only be purchased in limited amounts, and cannot be held within brokerage accounts, they possess severe drawbacks.

What about Treasury-Inflation Protected Securities, you may ask? (Indeed, you should, given that they feature in this article’s headline.) After all, their name assures the deed. Unfortunately, TIPS often fail to deliver on that promise. Over the short term, as shown during 2022, TIPS prices can decline while inflation rises. And over the long term, one cannot forecast the rates at which the yields from TIPS may be reinvested. Consequently, their future cash flows are indefinite.

How the Ladder Operates

There is, however, one exception: a TIPS ladder. With some effort, investors can create a TIPS portfolio that does, in fact, provide inflation-adjusted certainty of returns. The ladder’s nominal payments are unknown. But its real distributions can be specified in advance, with one minor caveat, which I will address shortly.

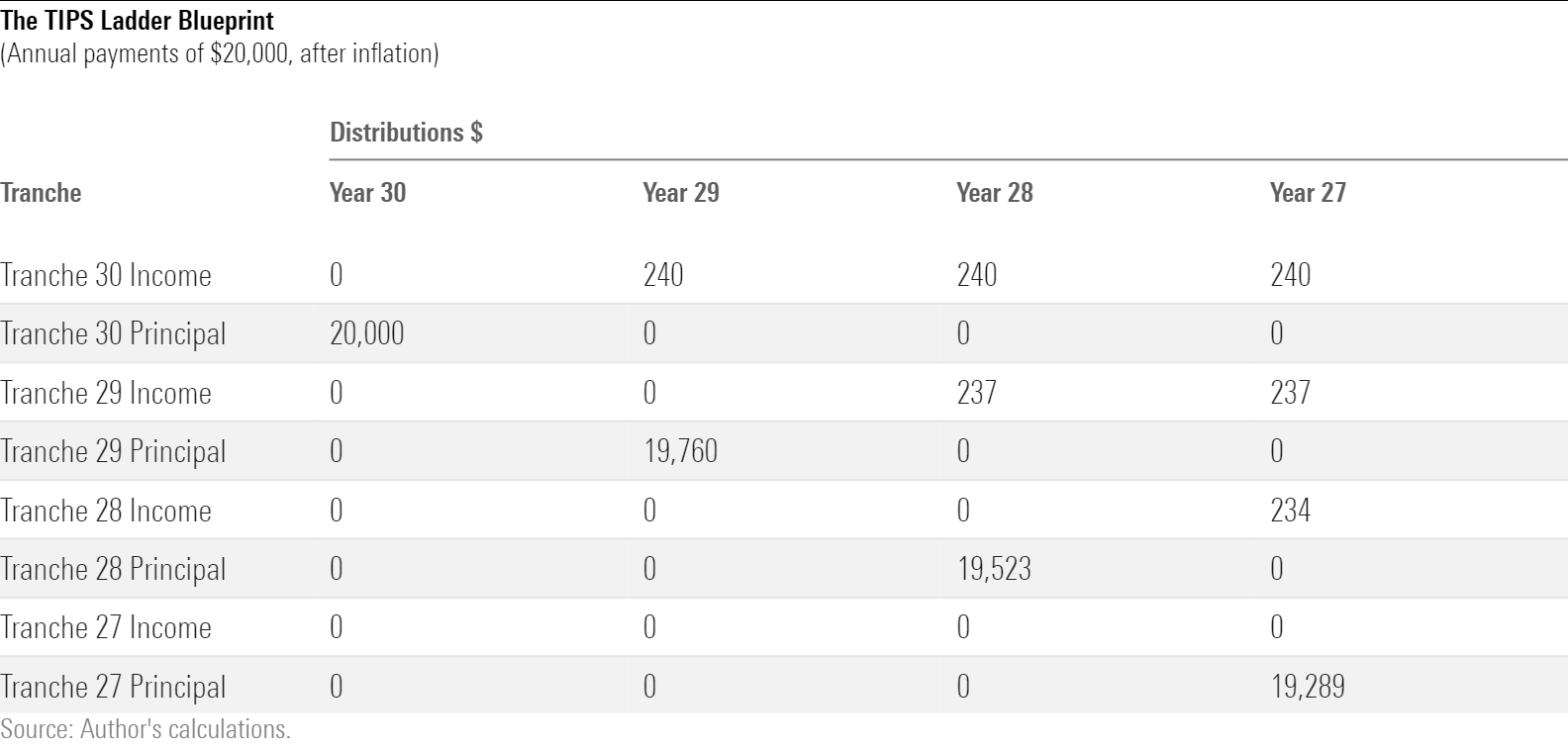

TIPS ladders are constructed by working backward. (For this section, I relied on Wade Pfau’s very helpful article, “How Do I Build a TIPS Bond Ladder for Retirement Income?”) Assume that an investor seeks a 30-year ladder, with each annual rung providing $20,000, expressed in today’s dollars. The payments start 12 months from now, which will we call the first day of Year 1. They will continue for another 29 years, until the first day of Year 30.

The first step is simple: buy a newly issued 30-year TIPS with a face value of $20,000. Thirty years from now, on the day in which Year 30 commences, the Treasury Department will redeem that security, thereby providing $20,000 of inflation-adjusted income. Voilà! Year 30 of the TIPS ladder has been addressed.

So far, so simple. The next step, Year 29, is not much harder. The bond that was purchased for Year 30 pays income in Year 29, so we need to account for its payout. At current prices, that amount will be $240, once again expressed in real terms. We therefore must buy $19,760 of TIPS that mature 29 years from now.

And so forth we proceed. (Technically, we should purchase 60 tiers of TIPS, because they pay semiannually, but never mind that. One tranche per year is close enough for amateurs.) The only complication is the aforementioned caveat, which is that because the Treasury stopped issuing 30-year TIPS for a while during the 2000s, no TIPS exist the mature between 2033 and 2039. The ladder will need to approximate by holding extra bonds entering and exiting that period.

For Example

The table below shows how the final four years of the ladder are funded. The process is identical for the preceding 26 years, albeit with increasingly many components.

A critical note: By design, a TIPS ladder exhausts the investor’s initial capital. It is not akin to an endowment strategy, which seeks ongoing income while at least maintaining, if not outright increasing, the investment pool. Rather, it is a spend-down strategy that offers the highly appealing feature of guaranteed payments, after inflation, but with the drawback of becoming a pumpkin at midnight.

In his recent article “The 4% Rule Just Became a Whole Lot Easier,” planner Allan Roth relates how he turned theory into practice by implementing the strategy. Fortunately, Roth found an online program to organize his ladder, instructing which bonds to buy. Completing his orders took some time, as the TIPS marketplace does not function as smoothly as, say, the stock market, but two hours later Roth had his portfolio.

Price Check

Now that you know how to build a ladder, should you? The response is no for those who earn more money than they spend, which presumably is the case for all workers reading this article. Such investors need no additional income at all, never mind that which is guaranteed, in all conditions, to offset inflationary rises.

The response, naturally, is more nuanced for retirees. It starts with cost. If TIPS are exceedingly cheap, TIPS ladders will carry broad appeal, even for those who are not much worried about future prices. If expensive, they are suited only for those who are especially inflation-wary, or who for some other reason must have more inflation-guaranteed income than is provided by Social Security.

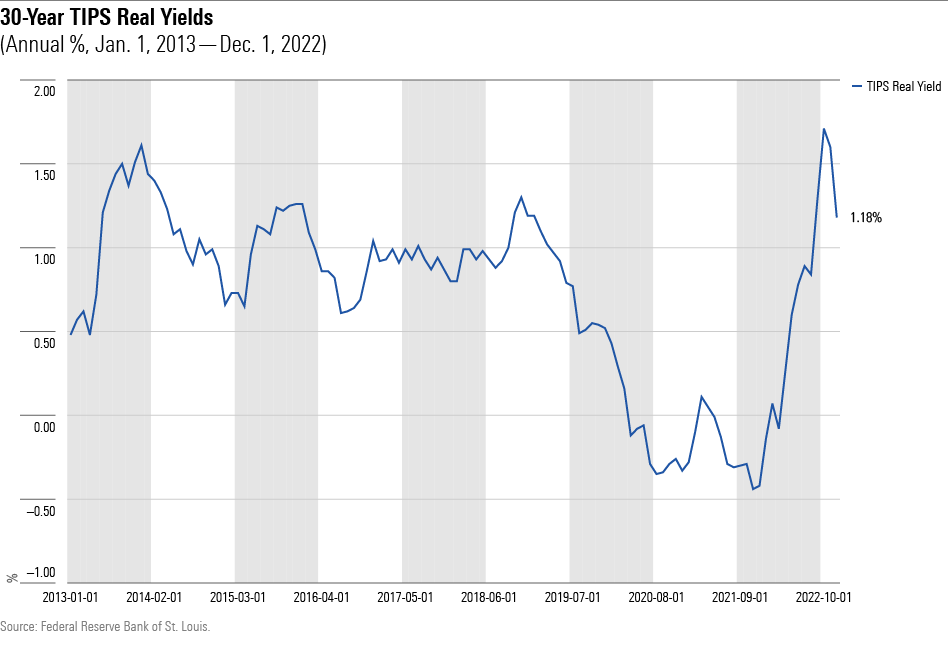

Addressing whether TIPS are currently affordable requires two views. One is how the ladder’s long bonds are priced. When Roth executed his strategy a mere two months ago, real yields on 30-year TIPS were at their highest level since 2011. (Confusingly, the explicit portion of a TIPS yield is called “real,” while that of an I Bond yield is named “fixed.” They are the same thing.) They have since shed half a percentage point, declining from 1.7% to 1.2%. That puts them slightly rather than strongly above their 10-year average.

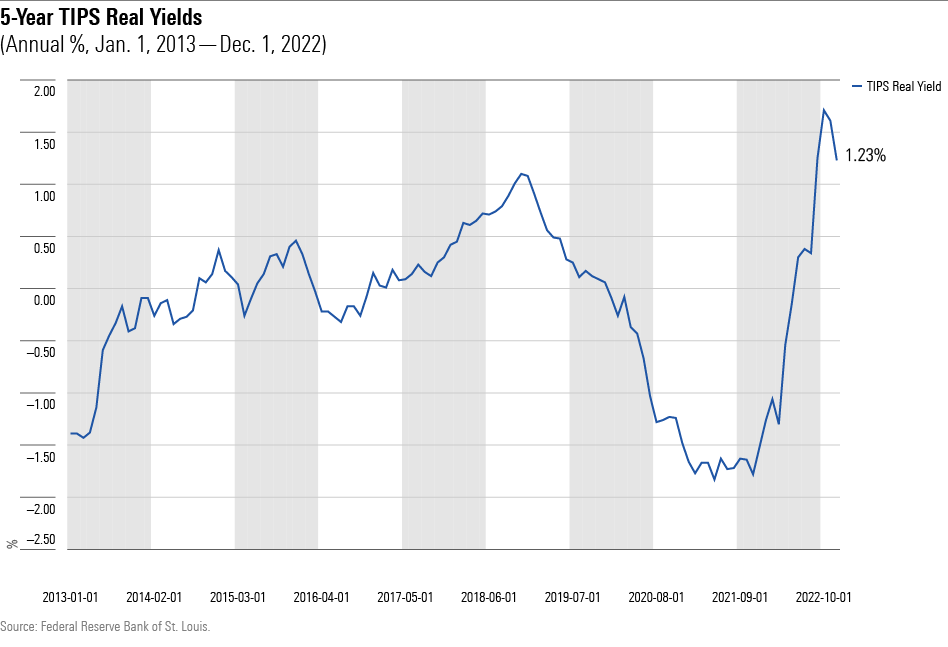

Long interest rates are only part of the story, though. A TIPS ladder also contains years that will arrive relatively soon. The news there is better. Presumably because the yield curve on conventional bonds has inverted, with short- to intermediate-term bonds now paying more than long bonds, real yields on five-year TIPS are unusually high. They, too, have dropped since Roth formed his portfolio—his timing was impeccable—but they remain far above their customary levels.

Summary

This column has discussed at a high level how TIPS ladders are constructed. It has also shown that TIPS are attractively priced. Which leads to two further questions. If I do build a TIPS ladder, what will be my return? And how does that result compare with what I could receive from other investment approaches? Those topics will be tackled in upcoming articles.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IFAOVZCBUJCJHLXW37DPSNOCHM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GQNJPRNPINBIJGIQBSKECS3VNQ.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)