Treasuries or Annuities? Choosing Between Two Sources of Guaranteed Income

The answer depends on the direction of inflation.

Seeking Income

Because the topic has not been personal, I have rarely written about investment income. That is no real excuse—Morningstar’s Christine Benz frequently does so, and she is considerably younger than I am—but such is the case. My imagination is limited. To address a subject properly, I need for it to feel relevant.

Income now does. That’s not because I intend to retire anytime soon. But as my 62nd birthday nears—the date at which I could start to collect Social Security, although I will not, because my situation benefits from delay—I find that my investment mindset has changed. It had always been “Why not 100% stocks?” Now I find myself considering the attraction of guaranteed income.

Today’s column addresses two possibilities: 1) Treasury bonds and 2) immediate lifetime annuities—that is, insurance contracts that deliver monthly checks for life, in exchange for an upfront investment. If this article sparks interest, I will expand the discussion to include Treasury-Inflation Protected Securities, corporate bonds, and municipal bonds.

Apples and Oranges

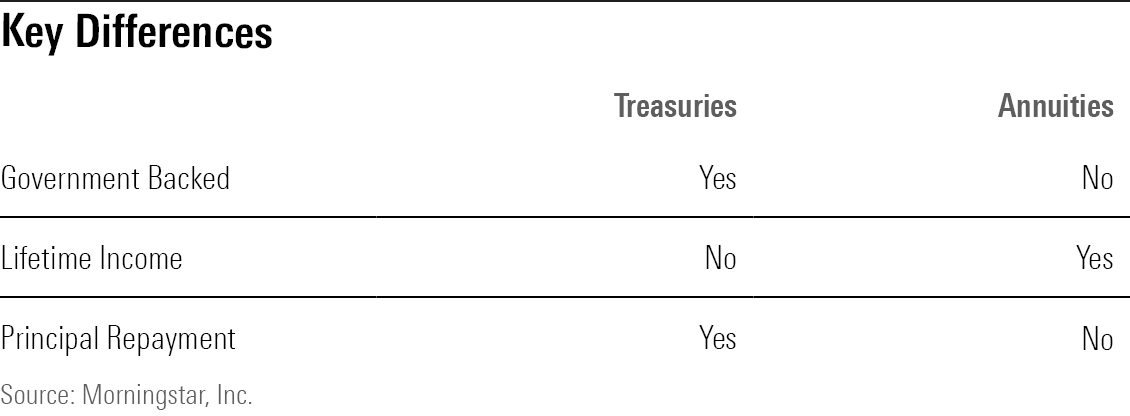

Treasuries and annuities contain three key differences.

There’s no way to address the discrepancy in credit quality. Treasuries have the full faith and backing of the United States government. They will meet their obligations, barring a catastrophe that sinks all investments but guns, gold, and oil. No such assurance exists for annuities, which are only as safe as the finances of the insurer that issues them. (That said, should an issuer become insolvent, each of the 50 states will reimburse at least $250,000 of an investor’s annuity.)

We can, however, assess which investment is the superior deal, should both fulfill their promises. This exercise does require some work. We need to find a way to adjust for the fact that Treasury bonds repay their investors’ principal, while annuities do not. That is, the payments from Treasury bonds represent true income, while annuity disbursements are a blend of income and capital return.

Here is how we will square the circle. One strategy for guaranteed income is to buy a 30-year Treasury bond, spend its distributions, and recoup the principal after year 30. Another would be to purchase a higher-paying annuity (higher paying because much of its outlays consist of capital return), spend what the Treasury bond earns, and stash what remains into a new investment account.

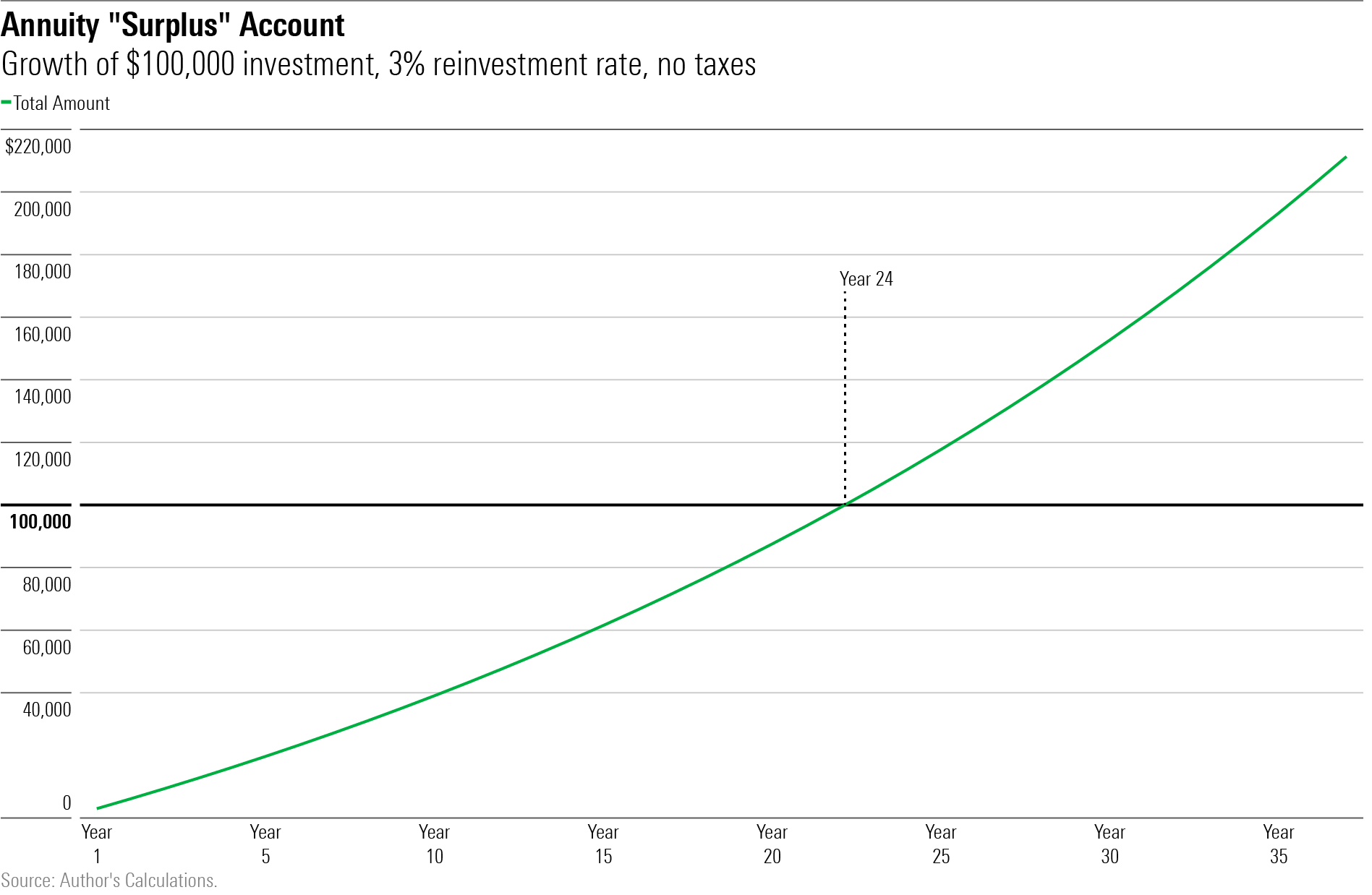

Over time, that surplus annuity account will grow, because each year it receives 1) new funds and 2) interest on its existing investments. The question then becomes, when does the investment pool generated by the annuity surplus exceed the principal repayment from the Treasury bond?

By the Numbers

Let’s do the work. Thirty-year Treasury bonds currently yield 3.86%. In contrast, a joint lifetime annuity for my wife and myself distributes an annual 6.83%. (If you tinker around on this site, you will be able to determine my wife’s age by reverse engineering, which is the only way that you will learn such information. Were I to state that number openly, I would be divorced, and thus the 6.83% rate would not apply). The math for the surplus account, assuming a $100,000 investment and a 3% yield on the surplus funds, looks like this:

1) Year 1: $6,830 in, $3,860 out, for a net gain of $2,970.

2) Year 1: No interest (I assume that the surplus funds are added at year-end).

3) Year 1: Final amount of $2,970 + $0 = $2,970.

4) Year 2: Another net gain of $2,970, making for a total pool of $5,940.

5) Year 2: Interest of $89.10, from the 3% reinvestment rate on year 1′s $2,970.

6) Year 2: Final amount of $5,940 + $89.10 = $6,029.10.

And so forth. The chart below provides the totals through year 30.

(Note: These calculations, you have noticed, assume the can opener of no taxes. That is because incorporating taxes into the model is messy. In general, though, thanks to their exclusion ratios, the annuity strategy fares even better after taxes.)

Reinvestment Rates

The annuity surplus account surpasses $100,000 invested in Treasury principal in Year 24. Thus, if my wife and I both die before Year 24, we will leave less money to our heirs by using the annuity strategy than if we had bought a Treasury bond. After Year 24, the reverse holds. Perhaps not coincidentally, our median joint life expectancy, per this calculator from financial planner Michael Kitces, is 24 years.

This result might be largely driven by the reinvestment-rate assumption. A 3% interest rate, achieved through a Treasury ladder, seems like a fair expectation for moneys that are to be placed into safe securities over the next 30 years. But, of course, we do not know what the actual reinvestment rate will be. The following table provides the outcomes for rates ranging from zero to 5%. The upshot: As long as the reinvestment rates are reasonable, rather than being either highly optimistic or almost nonexistent, the analysis does not much change.

- 5% withdrawal rate: 20 years to breakeven

- 4% withdrawal rate: 22 years to breakeven

- 3% withdrawal rate: 24 years to breakeven

- 2% withdrawal rate: 26 years to breakeven

- 1% withdrawal rate: 29 years to breakeven

- 0% withdrawal rate: 34 years to breakeven.

Conclusion

Ultimately, this is a judgment call. Buying the annuity means accepting credit risk. While that danger is low, as the annuity I selected comes from a company rated AA+ by Standard & Poor’s and AAA by Moody’s, it does exist. (Over the years, many insurers have gone bust, although few ever carried such a high credit rating.) On the other hand, the annuity keeps paying and paying. Should my wife or I live for, say, another 35 years, we would be far better served by the annuity.

My current preference, recognizing that my inquiries into this topic have just begun, is the annuity. Its protection against longevity risk is compelling. Should inflation not subside, though, neither choice will be particularly attractive. In such a case, TIPS would presumably prevail. They will be the next addition to my inquiry.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/VUWQI723Q5E43P5QRTRHGLJ7TI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/XLSY65MOPVF3FIKU6E2FHF4GXE.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)