Pros and Cons of Donor-Advised Funds

Donors benefit from an immediate tax deduction, tax-free growth, and investment flexibility.

A version of this article was previously published on May 17, 2021.

With the end of the year approaching, many investors are planning to wrap up their annual charitable donations over the next few weeks. For investors who plan to make significant contributions over time and want to maximize the tax benefits, donor-advised funds can be an attractive option. In this article, I’ll cover some of the basics of these funds, as well as how to decide whether they make sense for you.

The Basics of Donor-Advised Funds

A donor-advised fund is vehicle that allows investors to donate directly to a charitable fund while retaining some control over the assets. Donor-advised fund administrators are public charities that qualify as section 501(c)(3) organizations. That means donors can benefit from an immediate tax deduction when they contribute cash or other assets to the fund. Although contributions are irrevocable (meaning you can’t withdraw donations if you change your mind or need extra cash), the donor retains an advisory role over how to invest the assets and how much to contribute to various charities over time. Any remaining assets benefit from tax-free growth as long as the account remains funded.

Donor-advised funds have become increasingly popular in recent years. The National Philanthropic Trust estimates that assets in these funds totaled about $160 billion as of the end of 2020. There are several main types of donor-advised funds: those administered by a specific charity directly; those administered by a community foundation or religious organization (such as Jewish United Fund or Catholic Charities); and those administered by an organization connected with a financial institution, such as Fidelity, Schwab, or Vanguard. In this article, I'll focus on the third category, but the other two types are broadly similar.

The Pros

Tax advantages are one of the major benefits of donor-advised funds. That’s especially true after the 2018 tax-law changes, which made it more difficult to deduct charitable donations for tax purposes. Because most investors now take the standard deduction instead of itemizing, it can be beneficial to “bunch” charitable donations by making a larger donation in a single year, which might push you past the threshold for itemized deductions, instead of making smaller annual donations that might not be tax-deductible. Donor-advised funds can facilitate this strategy because donors can make a bigger contribution to a donor-advised fund in a single year and take the itemized deduction up front, but still make charitable contributions over time.

Donors contributing cash can take a deduction of up to 60% of adjusted gross income. (Individuals can currently deduct up to 100% of adjusted gross income in 2021 for donations made directly to qualified charitable organizations under the Consolidated Appropriations Act, but this is a temporary limit that doesn’t apply to donor-advised funds.)

In addition to cash, donors can contribute a wide range of appreciated assets, including stocks, bonds, mutual funds, privately held business interests, restricted stock, and even bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. Donors contributing securities or other assets can take a deduction of up to 30% of adjusted gross income. The in-kind tax deduction can be especially valuable for highly appreciated assets because it allows investors to remove these assets from their taxable portfolios (thereby improving diversification and mitigating security-specific risk) without taking the tax hit associated with the embedded capital gain. The donor-advised fund takes care of selling the appreciated asset, but there’s no realized capital gain to report.

Contributors to a donor-advised fund retain an advisory role over when and where to make charitable donations. Account holders can make donations all at once or over time, and to a single charity or a variety of charitable organizations. The main requirement is that donations go to a qualified charitable organization. Each donor-advised fund sets its own minimum amount for grants to charities; Fidelity and Schwab currently have $50 minimums, while Vanguard requires a $500 minimum grant.

Donors also retain control over how the remaining assets are invested. Investors can typically choose from several preset investment options with different risk levels, ranging from conservative, bond-heavy portfolios to more-aggressive, equity-oriented portfolios. Investors can either choose one of these preset portfolios or build their own portfolios using a longer list of single asset-class options. It's also possible to set aside some funds for upcoming donations in highly liquid securities (such as a money market fund) while investing other assets for longer-term growth.

Cons

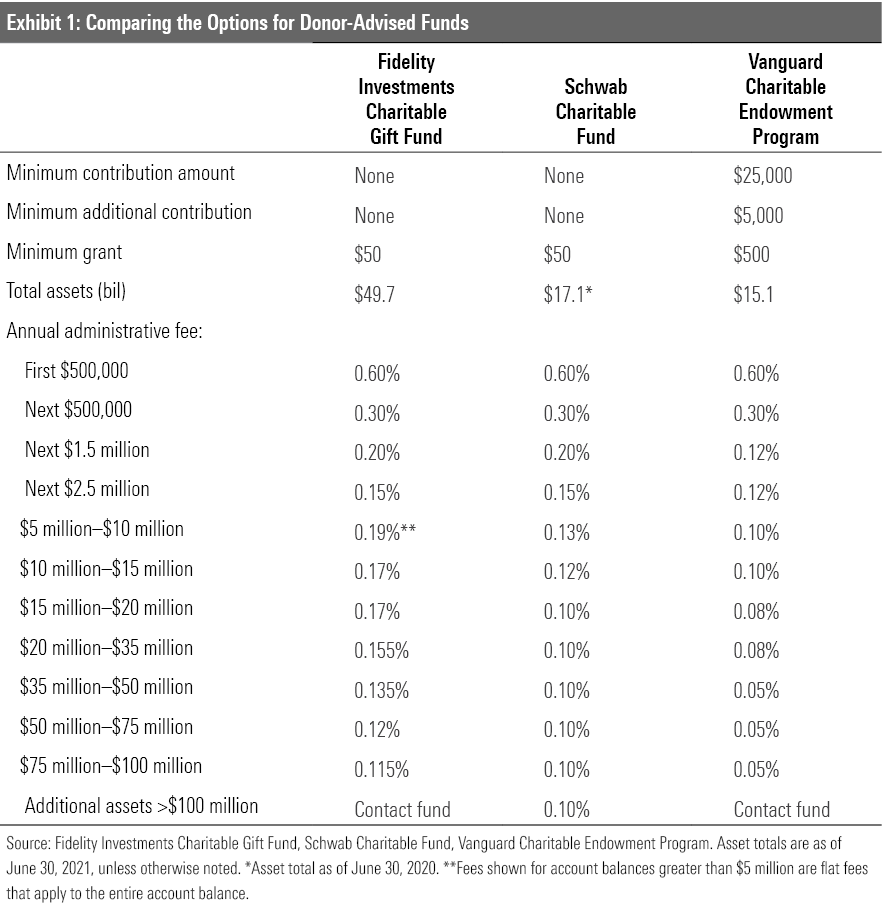

Despite their advantages, donor-advised funds aren’t the right choice for everyone. Although Schwab and Fidelity now allow investors to set up a donor-advised fund with any dollar amount, Vanguard Charitable currently requires a $25,000 initial contribution. Donor-advised funds also come with an additional layer of annual administrative costs. Fidelity, Vanguard, and Schwab all charge a 0.6% administrative fee for accounts with balances up to $500,000. All three have tiered expense structures, so accounts with balances greater than $500,000 are subject to lower fees in percentage terms.

These charges are in addition to the fees on the underlying investments (operating expenses for mutual funds and exchange-traded funds, or trading commissions for individual stocks and bonds). All these fees come out of the amount donated, making donor-advised funds less cost-efficient than donating directly to a charity.

Grants made to charities are also subject to a minimum donation amount. Schwab and Fidelity both require minimum grants of $50, while Vanguard requires a minimum of $500 for each grant. The account administrator must also approve each grant before funds are disbursed. As a result, investors who want to donate smaller amounts in cash might find it easier and more cost-effective to make donations directly, especially if they contribute to the same charities every year.

Some wealthier families and individuals might prefer to set up a private foundation to make charitable donations. A private foundation is a separate legal entity that has its own articles of incorporation, bylaws, and board of directors or board of trustees. Unlike donor-advised funds, foundations are required to file annual tax returns and distribute at least 5% of the previous year’s average assets each year, but they also have additional flexibility for making grants. For example, a private foundation can provide scholarships and fellowships directly to individuals, make direct grants to families or individuals facing hardships and emergencies, and run its own charitable programs.

Comparing the Options

The table below shows how three of the largest donor-advised funds stack up. Fidelity and Schwab are accessible to the widest swath of investors because they don’t require a minimum amount for initial contributions or additional contributions, but Vanguard offers lower administrative fees for larger accounts. (In fact, Vanguard recently made additional fee cuts for some higher-balance accounts.)

All three donor-advised funds offer a range of investment options, including both diversified asset pools with exposure to a range of asset classes, and single-asset pools that can be used as building blocks for donors to put together their own portfolios. Fidelity and Schwab offer both in-house funds and third-party offerings. Vanguard’s lineup consists almost exclusively of in-house funds, but nearly all the investment options are index funds with ultralow expense ratios.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IFAOVZCBUJCJHLXW37DPSNOCHM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GQNJPRNPINBIJGIQBSKECS3VNQ.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)