Are You Paying More in Fees Than Others for Your Retirement Investments?

It probably comes down to how big a company you work for.

For U.S. workers, the size of their defined-contribution plans could be a big deal. Large companies can usually offer plans containing low-fee investment options, while smaller businesses, lacking scale, have programs that cost participants more. Fortunately, most U.S. workers enjoy coverage through larger plans.

The Morningstar Center for Retirement and Policy Studies recently published its first Morningstar Retirement Plan Landscape Report, which puts hard numbers on the gap between large and small retirement plans and the effects it has on retirement savers. We found that more than 95% of plans in the United States qualify as small by our definition: plans with $25 million or less in assets. However, just 27% of workers are covered by these small plans.

(It's fair to assume that small plans are mostly offered by small employers and large plans are offered by large employers, but the unit of analysis here is the plan, not the size of the employer.)

Workers at Big Employers Pay About Half as Much as Those Working for Small Employers

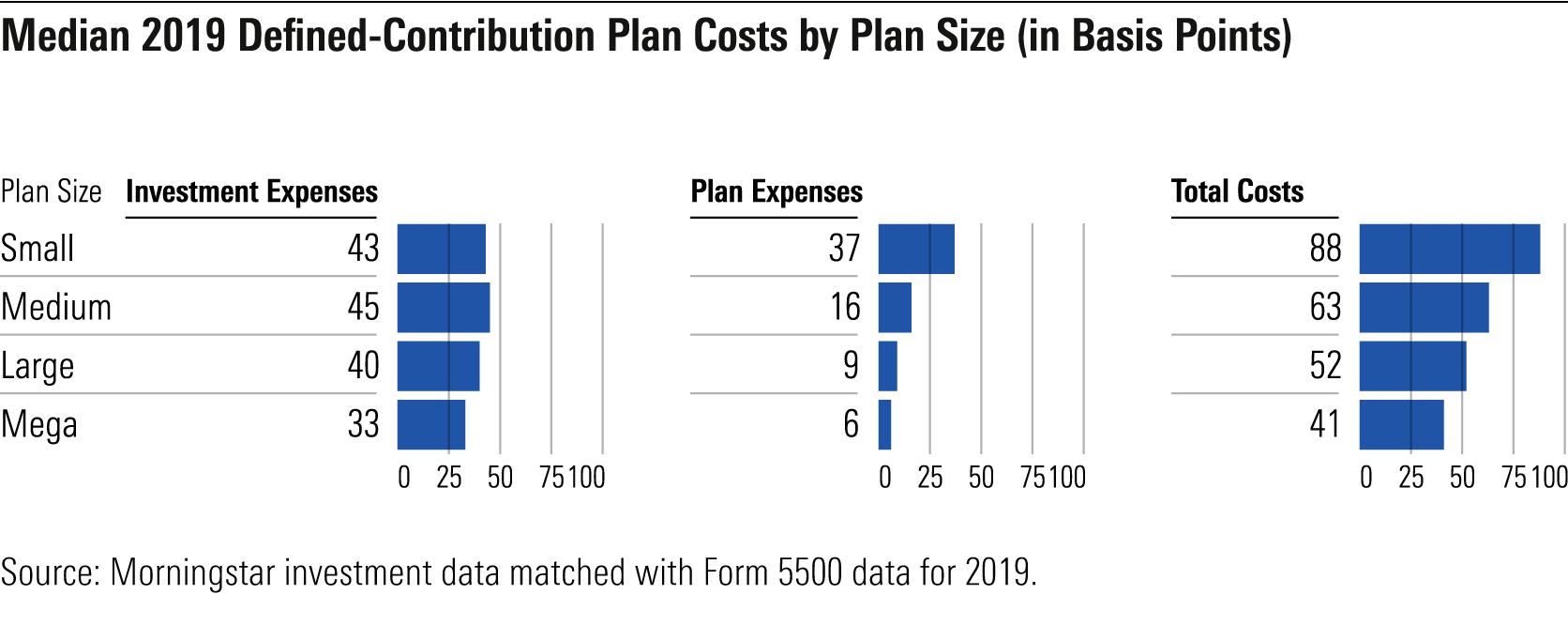

The median small plan costs participants twice as much as the median mega plan, dragging down returns. This is illustrated in Exhibit 1, which shows the asset-weighted expenses associated with the plan, overall plan administration expenses, and the all-in cost, which is the sum of both these numbers on a plan-by-plan basis. It's clear from the data that scale gives participants an enormous cost advantage.

(To fill in our definitions, mega plans have more than $500 million in assets; large plans have $500 million or less in assets, but more than $100 million; medium plans have $100 million or less in assets, but more than $25 million; and, as mentioned above, small plans have $25 million or less in assets. Remember, the median all-in cost is not the sum of the medians for investment expenses and plan expenses. Rather, we start with the sum of the investment expenses and plan expenses for each plan and then take the median.)

This is not an academic exercise. The difference in fees really does matter. Workers at employers with smaller plans who are saving just as much as those at employers with larger plans could have around 10% less in assets at retirement because of higher fees.

For this calculation, I use the difference between 88 basis points and 41 basis points and assume constant contributions over 35 years and steady 7% returns. Any set of reasonable assumptions will lead to a similar conclusion. Of course, workers may well switch employers during their careers and might go in and out of different plan sizes, but the point is the same: Workers in smaller plans are at a cost disadvantage to workers in larger plans.

Some Small Plans Offer a Much Better Deal to Their Participants Than Others

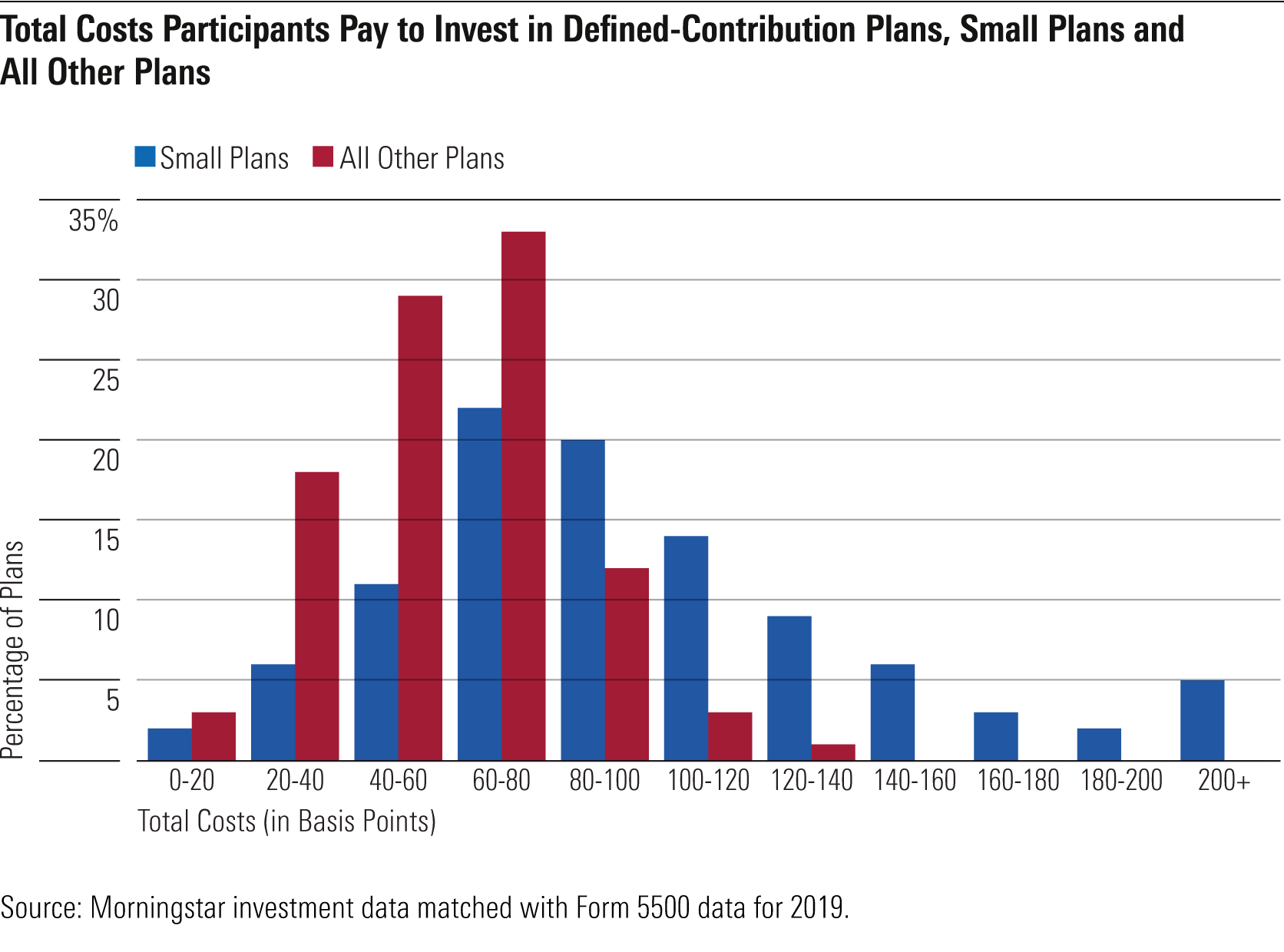

The spread of fees that retirement savers pay is particularly wide among smaller plans. Exhibit 2 shows the distribution of all-in costs for small plans and for all other plan sizes combined. The distribution for small plans is much wider than for larger plans, meaning that a small-plan participant is likely to pay more than a worker in a larger plan. Nonetheless, not all small plans are expensive. Some employers with small plans report all-in costs that are competitive with larger plans. In fact, 23% of small plans cost participants less than the median cost of 63 basis points for medium-size plans.

Midsize, large, and mega plans feature a smaller range of all-in costs. In other words, a participant would be more likely to pay fairly similar fees to invest in a defined-contribution plan no matter which company she worked for among employers offering plans of these sizes, as shown in Exhibit 2. Still, medium-size plans are less likely to consistently offer a good deal to their participants than larger ones. More than 20% of medium-size plans have all-in costs of more than 80 basis points, compared with just 1% of mega plans.

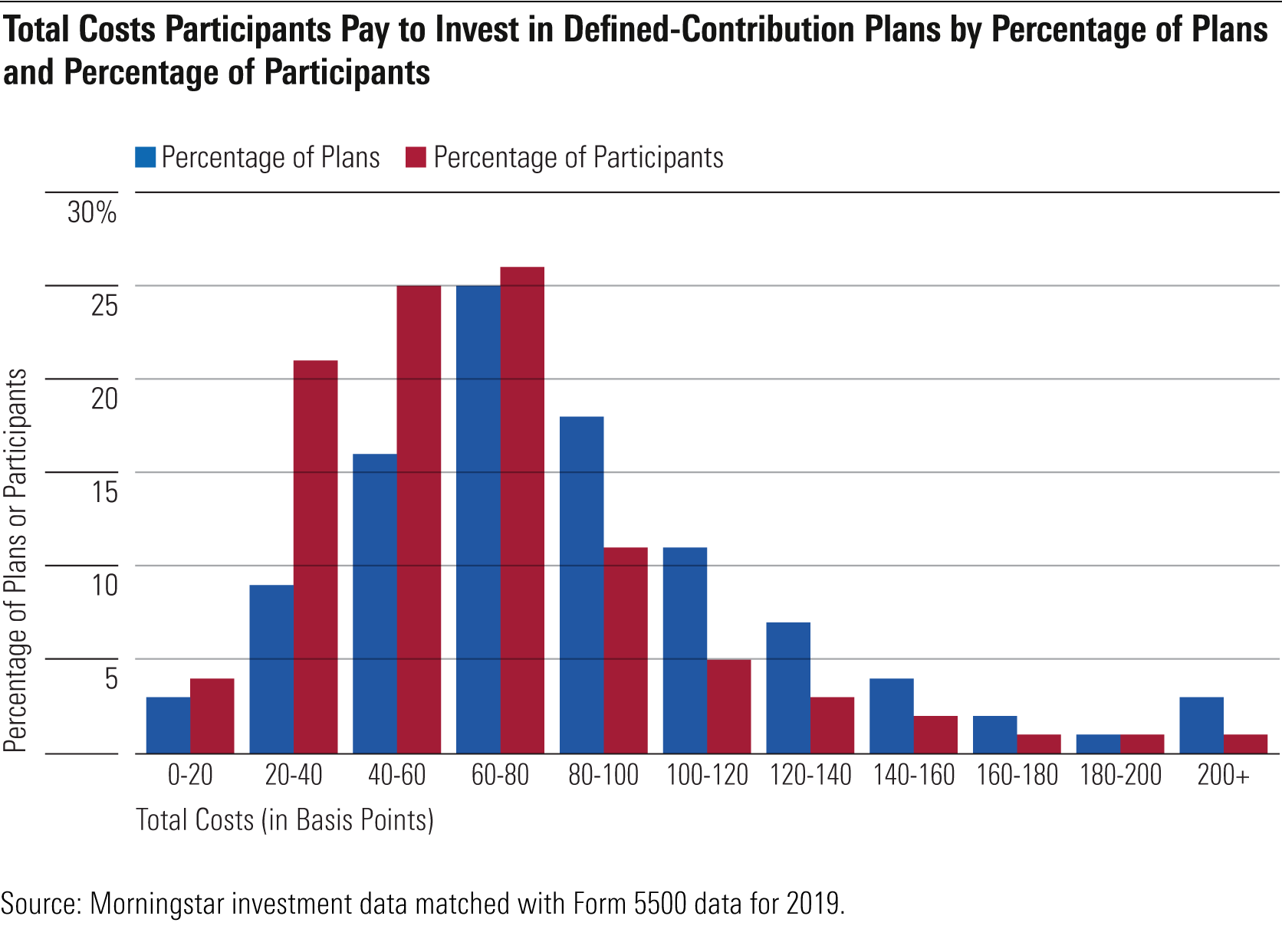

By summing the asset-weighted investment fees and the administrative costs, Exhibit 3 illustrates the wide range of the total fees across all plans that participants pay to save for retirement through defined-contribution plans. Because the largest plans often have low fees, most participants are in lower-fee plans.

Recent Policy Changes Could Help Small Plans Catch Up

The fact that small plans struggle to offer low-fee investments compared with larger plans partially motivated Congress to create pooled employer plans, or PEPs, at the end of 2019, with the first launching in early 2021. PEPs are similar to an existing but more restrictive structure for retirement plans, multiple-employer plans, or MEPs. The concept is that PEPs will allow more small employers to pool their assets to hopefully achieve the scale of large employers. As we discussed in detail in a 2020 paper, PEPs have the potential to reduce fees for participants as these new plans grow, but there will be challenges owing to the complex structure of allowing multiple employers to operate in one plan. Few employers have joined PEPs, although they have only been available for a little over a year.

Concluding Thoughts

Although we often think about plans in terms of the number of participants, it's really all about the amount of assets a plan has. Assets are what give plans leverage with fund companies to offer low-fee investment options to participants. PEPs are an opportunity for smaller businesses to increase the assets of their plans. If they take off, they could help level the playing field in terms of costs for all workers.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c6d5b386-6df4-434b-bf56-ac0c9546e5aa.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/KD4XZLC72BDERAS3VXD6QM5MUY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BZ4OD6RTORCJHCWPWXAQWZ7RQE.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c6d5b386-6df4-434b-bf56-ac0c9546e5aa.jpg)