China Is Running Out of Cheap Growth

The economy will soon exhaust its sources of easy productivity gains.

This article is the second in a series on China’s next 10 years.

Ever since China’s economy began to slow from last decade’s double-digit pace, investors have quarreled over the country’s growth prospects. At various times in the past several years, bulls and bears have each glimpsed apparent victory, only for a reversal of China’s credit cycle to hand narrative momentum to the other side. The long-term outlook remains unsettled, and the debate continues.

Perhaps no question matters more to investors globally. Over the past 10 years, China has been the single largest contributor to global GDP growth, accounting for nearly one third of the world total. Meanwhile, China has become the world’s biggest buyer of everything from automobiles to airplanes to oral hygiene products.

The bullish side of the debate often points to China's remaining potential for "catch-up" growth, which should portend slower, albeit robust growth for many years to come. As a whole, China remains poorer and more agrarian than rich countries. Within China, there's scope for catch-up, too. Interior provinces are far less developed than their coastal peers. Prominent bull Justin Yifu Lin, former chief economist at the World Bank and longtime advisor to top leadership in Beijing, has long cited China's relative poverty as the biggest reason for his optimism.1 He notes that Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea all enjoyed decades of 7%-plus GDP growth after they had reached the rung on the income ladder that China finds itself at today.

Others are more circumspect. Over the past half-century, the typical country at China’s income level posted 4% average annual GDP growth in the 10 years that followed. That’s well below the consensus medium-term outlook for China of roughly 6%, as well as Beijing’s goal of 6.4% through 2020. Bears fret that even an “average” outcome would be optimistic, given the excesses that have built up following repeated rounds of stimulus and the disappointing pace of reform.

This article continues our series on China's next 10 years with our take on the growth debate.2 We aim to look beyond prevailing trends and recent headlines that tend to dominate the discussion. Our long-term orientation requires a different focus: the rich academic literature on economic development, the history of other countries that encountered many of the challenges China faces today, and the role China's political economy may play in promoting or inhibiting growth.

In this article, we’ll probe the sources of China’s multiyear slowdown. Why, exactly, has growth slowed? Are the underlying causes of the slowdown likely to persist, abate, or worsen?

Why Has Growth Slowed? China's economy has slowed markedly this decade. But the extent of the slowdown is debatable. Government statistics portray a gradual decline— an apparent soft landing for what had been the world's highest-flying economy. By contrast, most independent estimates, such as those from economist Harry X. Wu,3 suggest a bumpy descent punctuated by periodic bursts of stimulus.

Few expect a return to high-single-digit growth in the years to come, much less the double-digit pace of the prior decade. But many believe growth is unlikely to slow much further from the prevailing rate (6.8% in the third quarter of 2017). The International Monetary Fund envisions China’s GDP growth averaging 6.1% through 2022. Most sell-side analysts expect something similar, although a minority express a more bearish view. We forecast average annual GDP growth of slightly less than 4% through 2026.

In pondering the long-term trajectory of China’s economy, it’s instructive to first consider the underlying sources of the country’s slowdown. We start with a breakdown of GDP into its constituent parts. At the most basic level, a country’s economic output is the product of three inputs: capital, labor, and productivity. An economy grows by accumulating capital (for example, a new factory is built), adding labor (the factory hires unemployed workers), and increasing productivity (the factory adopts a new technology).

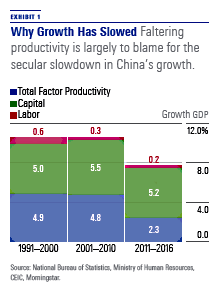

We can use this standard framework (specifically, a Cobb-Douglas production function) to estimate the contributions of capital, labor, and productivity to China’s GDP growth. To identify secular shifts in China’s growth pattern, we focus on average annual growth rates for each of the past three decades (1991–2000, 2001–10, and 2011–16) rather than year-by-year estimates ( EXHIBIT 1 ).

- source: Morningstar Analysts

Faltering productivity appears to explain much of the economy’s recent deceleration. We estimate average productivity growth at 2.3% in the current decade, down from 4.8% in the 2000s.

Weaker productivity gains account for roughly three fourths of the total decline in GDP growth over this interval (2.4 percentage points of the 2.9-percentage-point reduction in GDP growth).

And it's possible the narrative is a bit darker than it might otherwise appear. That's because our productivity growth estimates rely on official GDP figures. To the extent government statistics overstate China's GDP growth, they may also understate the degree to which productivity growth has fallen. Using unofficial GDP figures, recent productivity growth has been meaningfully lower, possibly negative.4

In contrast with the slowdown in productivity growth, the contribution from capital accumulation has remained elevated. Net additions to China’s capital stock have contributed 5.2% to GDP, on average, in the current decade, down only slightly from 5.5% in the 2000s.

The economy has become increasingly dependent on capital accumulation as a source of growth. Since 2010, net capital additions have accounted for nearly 70% of GDP growth, up from roughly half in the prior two decades.

This is a natural consequence of the government’s desire to prop up growth. Whereas Beijing cannot easily boost productivity or the labor supply in the near term, it has considerable influence over the rate of capital accumulation.

The government’s decision to keep capital spending elevated despite a shrinking set of high-return projects is a big reason productivity growth has faltered. More importantly, because each round of stimulus delivers yet another blow to productivity, Beijing is likely to find it more difficult to engineer the desired GDP growth rate.

While the contribution from labor supply growth has slipped in the current decade, the decline has played little direct role in slowing overall GDP growth. As discussed in our first article, changes in labor supply will continue to have a larger impact on the composition of GDP than on its size—shifting income to households from corporations and lifting consumption at the expense of savings and investment.

Why Has Productivity Growth Faltered? Why is China finding productivity gains harder to come by? Mainly because four conditions that made rapid productivity growth possible in the post-Mao era no longer exist.

The Imitator Must Become an Innovator First, China is no longer a technologically “backward” country that can generate easy productivity gains by copying more sophisticated foreigners. Arguably, no major country has capitalized on the opportunity afforded copycats as well as China. Rapid absorption of foreign technology is evident in the growth of the country’s manufacturing sector. Since 1990, Chinese manufacturing exports have grown at a 15% compound annual rate and are now 50 times larger in nominal U.S. dollar terms. By 2015, China accounted for 19% of global manufacturing exports, up from 5% in 2000 and 2% in 1990. China’s success as an imitator is attributable to four factors: fortunate timing, an ideal location, strong government support, and a vast domestic market.

While China’s rapid technological catch-up has proved a major boon to growth, it naturally leaves less scope for productivity-enhancing copycat behavior going forward. Increasingly, Chinese firms will need to innovate, rather than imitate. And innovating is a lot harder to do.

The Rural Labor Surplus Dries Up Second, as China has urbanized and industrialized at a pace possibly unprecedented in human history, the scope for boosting productivity by moving ever more farmers to factories or storefronts is now more limited.

For countries in the early stages of economic development, labor migration from farms to factories tends to be a major driver of economic growth. That’s because workers in the industrial and services sectors are far more productive than agricultural workers. Based on official figures, the typical Chinese factory worker is roughly 4.5 times more productive than his farming counterpart.

Labor migration has been a key source of productivity growth for China in the past few decades. According to official statistics, employment in industry and services has risen by 303 million people since 1990, while agricultural employment contracted by 175 million (total employment expanded 128 million). Over the same interval, China’s official urbanization rate rose to 57% from 26%.

Having urbanized at a possibly unprecedented pace, China’s agricultural workforce is much smaller than it once was. But how much smaller? That’s debatable. It’s an important question as we consider the scope for continued productivity-enhancing labor migration. China’s National Bureau of Statistics estimates the country’s agricultural workforce at 215 million in 2016 (28% of the total workforce), down from 389 million in 1990 (60% of the total), which would suggest China is a long way from exhausting labor migration as a source of productivity growth.

Academic studies indicate far fewer farmers remain.5 Based on these studies, it's possible China's agricultural labor force might have slipped to roughly 150 million, which would represent 19% of the country's 2016 workforce, well below the 28% estimated by the National Bureau of Statistics. Meanwhile, labor migration to urban areas has slowed by half in the past several years, and the population of migrant workers under 30 years old has been declining since 2008.

This isn’t to say that Chinese farmers will stop moving to cities, only that fewer will make the trip in the years to come. That implies additional downward pressure on productivity growth. It also means decelerating urbanization.

Whereas moving farmers to factories and storefronts involved both spatial (rural to urban) and sectoral (agriculture to industry and services) reallocations, future changes to China’s labor mix will be mainly sectoral (industry to services). This process has already begun. China’s industrial workforce peaked at 232 million in 2012 and slipped to 224 million by 2016. Over the same interval, service-sector employment rose from 278 million to 338 million.

The reallocation of labor from industry to services will generate far less productivity growth than the shift out of agriculture. That's because, according to the World Bank, the "productivity differences between industry and services are not as high as those between agriculture and industry."6

High-Return Projects Will Get Even Harder to Find Third, decades of rapid capital accumulation have left China with far fewer high-return projects than were available at the dawn of the reform era.

Despite enormous additions to the capital stock, economywide returns on investment remained impressively high for most of the reform era. This was partly due to decades of economic mismanagement under Mao, which left China with a paltry capital stock and an ample array of promising investment opportunities. More important, however, were continued reforms that boosted returns and improved capital allocation.

Since 2008, however, returns have faltered due to repeated stimulus and stalled reforms. China’s total capital-output ratio, which measures how efficiently the country’s total capital stock is being put to use, has deteriorated amid overinvestment across vast swaths of the economy.

China’s incremental capital-output ratio, which measures how efficiently new capital is being used, looks even worse. China generates 50% less GDP for each new unit of capital than it did in 2007.

Today’s China can no longer rely on brute capital accumulation as a major source of productivity gains. If anything, maintaining the current level of spending would likely reduce productivity growth. Overinvestment and overborrowing are direct consequences of China’s political economy, which prioritizes (and incentivizes) growth at all costs and does not subject government-linked borrowers to market discipline.

These problems are structural and, as such, cannot be solved with political discipline. Beijing’s frequent admonitions of reckless borrowing and spending by provincial and local governments have had little impact over the years. Nor are administrative measures (for example, President Xi Jinping’s various “supply-side reforms,” which include capacity reduction quotas, debt/ equity swaps, and hybrid ownership structures) likely to have lasting consequences.

That’s because until Beijing abandons overly ambitious GDP growth targets, repeated stimulus efforts are likely. And until local governments and state-owned enterprises face hard budget constraints, they will be able to borrow and invest to meet those growth targets. Barring true structural change, returns on capital will deteriorate further, bad debt will continue to accumulate, and productivity growth will come under added pressure.

The Demographic Window of Opportunity Is Closing Finally, China’s “demographic dividend” has been spent: After nearly doubling in size since 1980, the country’s working-age population is now shrinking, reducing the savings available to fund productivity-enhancing investments.

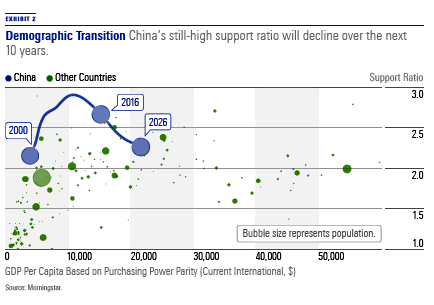

China’s family planning laws triggered a premature drop in fertility. From 1970 to 1980, China’s fertility rate plunged from 5.7 to 2.6 births per woman, an unprecedented decline for what was still a poor, largely agrarian country. While that led to an immediate slowdown in population growth, the working-age population continued to expand, from 582 million in 1980 to nearly 1 billion by 2010. Over that time, China’s support ratio—the number of working-age adults for every child and senior— surged from 1.5 to 2.9. As theory would predict, China’s household savings rate surged, facilitating rapid (and, for a long time, productivity-enhancing) capital accumulation.

Low fertility prematurely closed China’s demographic window of opportunity. The working-age population has begun to contract. The demographic support ratio, while still high, has begun to slip ( EXHIBIT 2 ), and so too has the household saving rate. Over the next 10 years, China’s support ratio will fall further, from 2.7 to 2.3. For every 10 dependents, China will have four fewer working-age adults than it does today. The household savings rate is likely to fall further, draining the pool of funds available for investment.

- source: Morningstar Analysts

Without major structural reforms, borrowing by local governments and state-owned enterprises would increasingly crowd out private enterprises, economywide returns on investment would continue to deteriorate, and productivity would falter further.

How Much Further Will Productivity Growth Fall? China's economy will soon run out of the cheap fuel that kept it flying high for so long, complicating Beijing's efforts to keep growth aloft. Over the next 10 years, technological progress will decelerate as firms must innovate rather than imitate, urbanization will slow as the rural labor surplus is exhausted, returns on capital will deteriorate as overinvestment makes high-return projects ever scarcer, and the country's demographic window of opportunity will close. Productivity growth is likely to slow from its recent pace of about 2.3%, dragging GDP growth down with it. But by how much? History offers some clues. Over the past five decades, the typical country at China's rung on the income ladder generated 0.7% average productivity growth in the subsequent 10 years. Notably, less than one fourth of those countries enjoyed the 2%-plus annual gains implicit in consensus forecasts for China.

More ominous is the possibility that productivity growth utterly stagnates—roughly one third of countries at China's income level saw flat to negative productivity growth for an entire decade. Academic research suggests flatlining productivity is especially common among previously fastgrowing middle-income countries,7 a phenomenon that World Bank economists Indermit Gill and Homi Kharas coined the "middle-income trap."

Stagnating productivity among middle-income countries explains why comparably few ultimately become high-income countries. Among the 96 countries categorized as low- or middle-income in 1960, only 12 non-OPEC members eventually graduated to high-income status. This is the leap China aims to make, which would involve more than doubling GDP per capita from today’s level.

Worryingly for China, the historical record suggests that it may be getting harder for middle-income countries to ascend to high-income status. Of the 12 non-oil middle-to-high transitions since 1960, only four have occurred in the past 30 years: Taiwan, Ireland, Spain, and South Korea. Just as many middle-income countries fell back to low-income status over the past 30 years (Nigeria, Nicaragua, Barbados, and Jamaica). In our next article, we will gauge the risk that China falls into the middle-income trap.

1 Lin, J.Y. 2013. “Long Live China’s Boom,” Project Syndicate, Aug. 5.

2 Our first article focused on the economic implications of demographic change, including detailed analysis of fertility, aging, and urbanization. See “China’s Next 10 Years,” Morningstar magazine, June/July 2017, pp. 60-63.

3 Wu, H.X. 2014. “China’s Growth and Productivity Performance Debate Revisited—Accounting for China’s Sources of Growth with a New Data Set,” The Conference Board, January.

4 Ibid.

5 See Brandt, L., Hsieh, C., & Zhu, X. 2008. “Growth and Structural Transformation in China,” China’s Great Economic Transformation (Cambridge University Press); Cai, F. & Wang, M. 2008. “A Counterfactual Analysis on Unlimited Surplus Labor in Rural China,” China & World Economy, Vol. 16, Issue 1, pp. 51-65; Dong, Q., Murakami, T., & Nakashima, Y. 2015. “The Recalculation of the Agricultural Labor Forces in China,” July.

6 World Bank and the Development Research Center of the State Council, the People’s Republic of China. 2014. Urban China: Toward Efficient, Inclusive, and Sustainable Urbanization, World Bank.

7 See, for example, Eichengreen, B., Park, D., & Shin, K. 2012. “When Fast-Growing Economies Slow Down,” Asian Economic Papers.

This article originally appeared in the December/January 2018 issue of Morningstar magazine. To learn more about Morningstar magazine, please visit our corporate website.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ecf6f262-5697-406a-a91d-cd20ff52a617.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/PKH6NPHLCRBR5DT2RWCY2VOCEQ.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GJMQNPFPOFHUHHT3UABTAMBTZM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZYJVMA34ANHZZDT5KOPPUVFLPE.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ecf6f262-5697-406a-a91d-cd20ff52a617.jpg)