Why Fund-Company Acquisitions Rarely Succeed

Mergers lead neither to lower expense ratios nor stronger fund performances.

Tough Odds

There have been exceptions to this headline’s generalization. BlackRock’s BLK 2009 purchase of Barclays Global Investors has been lauded as a “once in a lifetime” deal; through acquisitions, Invesco IVZ has assembled a large U.S. business; and Franklin Resources BEN extended its reach in 1992 when it complemented its domestic operations by buying foreign-stock manager Templeton Investments.

Overall, though, fund company acquisitions have a poor track record. A recent and particularly unpleasant reminder of that fact occurred last week, when the aforementioned Franklin bought Putnam Investments, for $925 million. In 2007, Great-West Lifeco GWLIF acquired Putnam for $3.9 billion. That deal, to understate the matter, was distinctively unsuccessful. Since that time, U.S. equities have tripled in value, while Putnam shed 75% of its net worth. Ouch!

To be sure, such disasters are infrequent. (Happily, Morningstar’s Greggory Warren does not think that Franklin will share Great-West Lifeco’s fate.) Most fund company acquisitions cause little damage—but they also provide little benefit. The hope when buying a fund company is to make 1 + 1 equal more than 2. It is mostly forlorn. Overall, estimate researchers, 70%-80% of corporate mergers are unsuccessful. The percentages are lower yet within the fund industry.

Flat Costs

One way fund companies can benefit from acquisitions is to slash their ongoing expenses. Combining two smaller entities into a single larger business creates that opportunity, by shrinking the company’s general and administrative burden. This event usually does occur, although not painlessly, because the exiting corporate staff receives severance pay, and perhaps also “consulting” contracts that reassure concerned clients by keeping their names on the books.

Regrettably, this low-hanging fruit is relatively small. For example, Franklin spends 6 times as much on obtaining and serving clients as it does on overhead. Thus, if an acquiring fund company can somehow manage the laudable feat of slashing its general and administrative payments by one third (expressed as a percentage of corporate revenue), doing so would decrease its total costs by only 5%.

The bigger line item usually escapes untouched. Almost always, fund companies buy organizations that are based elsewhere. What then to do about the newly inherited offices? It’s one thing to permit employees who are scattered across the country (or perhaps even the globe) to work remotely. It’s quite another to shut down the home of an entire business unit. Companies seldom do so.

Personnel Issues

Nor can they easily relocate their new employees. Some will move, but most will not. Perhaps one can cajole autoworkers into uprooting their families to follow an auto plant that has been transplanted to another state. Not so much financial-services jobholders, who typically have other options for employment. They stay put—meaning that so, for the most part, does the cost of maintaining their offices.

Cutting headcount is also difficult. If the acquiring organization maintains the funds that it purchased, those investments require their own portfolio managers, product chiefs, sales force, and so forth. The status quo persists. There is the possibility of “rationalizing costs” by merging funds, but that step must be taken carefully lest shareholders revolt. The surviving fund, after all, is not the fund that they originally purchased. They may decide it is not worth retaining.

In short, fund companies that make acquisitions struggle to reduce their costs significantly. That failure not only affects their profit margins, but also (of greater importance to their customers) their funds’ expense ratios. Nothing much will change.

Performance Challenges

Besides achieving economies of scale, historically two other goals have motivated fund company acquisitions: 1) bolstering distribution and 2) upgrading performance. I will skip the former for two reasons. One, it is immaterial for fund shareholders. If their funds become more widely available, they are neither helped nor harmed. Two, as the industry shifts from mutual funds to exchange-traded funds, the issue has become less important. An ETF may readily be purchased by anybody.

Improving performance remains relevant, of course. One approach consists of procuring technologies rather than increasing current assets. For example, in 2021 Vanguard bought a direct-indexing provider, Just Invest. The purchase did not directly (so to speak) increase Vanguard’s coffers. However, it provided the company with a platform that could be used to offer additional services.

Such investments, while often sensible, are also beside the point. Fund companies spend much more on—as with Great-West Lifeco’s ill-fated purchase of Putnam—obtaining fund assets. Usually, such announcements are accompanied by plaudits for the research prowess of the acquired organizations. They will benefit the new company, we are told, by supplementing their existing skills.

Not so much. For one, if those research groups were so powerful, then their funds’ performances would likely have been robust enough to prevent the company from being acquired in the first place. Few fund organizations that are growing their market shares agree to be purchased. For another, even if their research truly is excellent, integrating that capability into the rest of the organization rarely occurs. The same silos that prevent employees from working in a single office prevent them from collaborating on investment research.

Consequently, few fund company acquisitions have led to meaningfully better fund performances. Costs have remained broadly similar, as have the funds’ research organizations. It should come as no surprise, then, that their returns have not much changed.

Wrapping Up

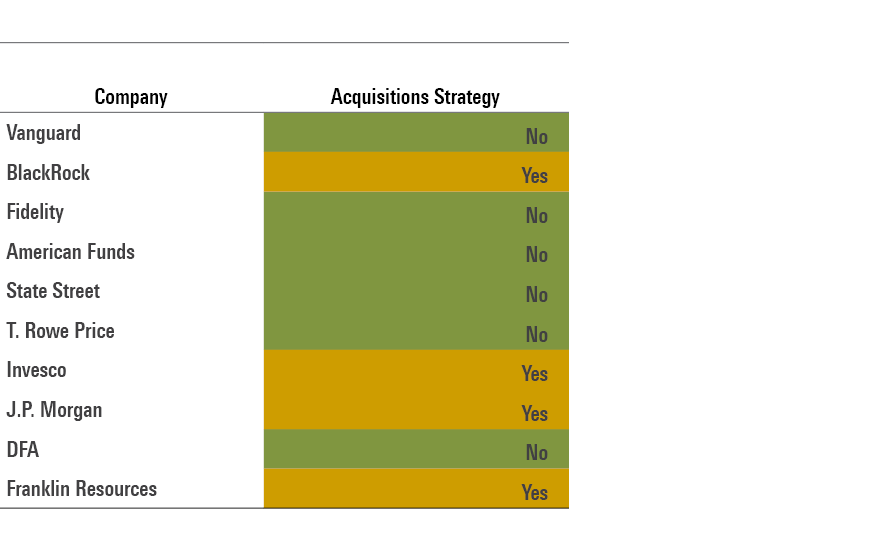

Over the past 40 years, fund executives have collectively made hundreds of purchases. Yet despite all that activity, most of the very largest fund companies earned their position through internal growth. This article concludes with a table that shows the 10 largest mutual fund and/or ETF providers, as measured by their size of U.S.-based assets, along with a description of their acquisition strategy. (“Yes” means that they have at least once bought a substantial fund company.)

As you can see, most of the winners triumphed by investing internally. The healthiest fund companies generally do not require the kindness of strangers.

The 10 Largest Fund Managers

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)