How to Choose Great ETFs for the Long Term

Avoiding problematic ETFs goes a long way.

Exchange-traded funds have evolved a lot over the past 30 years, leading to a staggering number available to investors. A quick glance at the full list is dizzying to say the least. Nearly 3,400 ETFs traded on US exchanges at the end of December 2023, a vast menu that includes ETFs of all shapes and sizes. Even some of the industry’s largest active managers that historically stuck to mutual funds have started offering their strategies through an ETF in recent years.

Initially, that sounds great. More ETFs equate to more choices, which increases the likelihood that investors can find an ETF that fits their needs. From that perspective, more is better, right?

Maybe not. Evidence from social science research suggests the opposite. Too many options can actually make decisions more difficult. That said, some simple screens can pare down the extensive list of choices and increase your chances of selecting a great ETF for the long haul.

Too Many Options

Researchers have studied the impact of menu size on consumer choices for years. One such experiment from Sheena Iyengar (Columbia University) and Mark Lepper (Stanford University) is perhaps the most well-known example. Multiple authors and publications have referenced their infamous “jam choice” experiment since it was first published in 2000.[1]

Iyengar and Lepper used a simple experimental setup. They built two displays in an upscale supermarket that offered shoppers the opportunity to sample a selection of jams. The first display had a limited set of six jams, while the second offered a more extensive menu of 24.

If “more” equates to “better,” then the display with two dozen choices should have led to greater interest and more sales. But the results didn’t validate that hypothesis. The 24-jam display attracted more visitors, but the smaller display sold considerably more jam, despite less interest from shoppers.

What’s going on? Iyengar and Lepper suggested that too much choice hampered shoppers’ motivation to make a decision. Other studies have confirmed these results, including those looking at the number of mutual funds offered through employer 401(k) plans.[2] The results hold up regardless of the underlying reason: More choices lead to less action.

Navigating the ETF Supermarket

The ETF market isn’t that different from the supermarket. The number of ETFs has grown immensely over the past 20 years, from a little more than 100 at the end of 2003 to nearly 3,400 at the end of 2023.

The vast array of investment strategies underlying modern-day ETFs further complicates the decision. A majority of those available 20 years ago tracked straightforward market-cap-weighted stock indexes that represented the broader market or segments of the market. But all sorts of differentiated strategies are available today, from broad funds that employ alternative weighting approaches to niche thematic strategies and single-stock ETFs.

Innovation along these lines seldom translates to long-term investment merit. Many of the ETFs available today have a minuscule amount of money behind them and won’t survive the next five years let alone the next decade. Many lack the basic features that drive great long-term performance, such as low fees and a diversified portfolio. Even fewer will likely meet or exceed the broader market’s rate of return.

Some simple screens can help whittle the field down to those more suitable as long-term investments. These screens represent the early stages of the research process, and they are by no means the end. The goal is simply to move away from the table with 24 jams to one with five or six and arrive at a better place to perform deeper analysis.

Cutting ETFs that face existential risk takes quite a few off the table. Those with less than $100 million are most likely to shut down in the near term. Almost 1,600 ETFs, or roughly half of the 3,400 available at the end of December, fit that description.

A stricter $1 billion threshold confers some additional benefits. It cuts the pool down to just 599 ETFs. While nothing is guaranteed, those reaching the $1 billion mark are more likely to stick around. It takes time, often years, to grow that large. The median life span of those 599 ETFs was 13.5 years, meaning most have a substantial track record that helps facilitate further analysis. Their real-world performance can be vetted against expectations. And their mature markets likely reduce trading costs for investors compared with newer ones.

Eliminating smaller ETFs to focus on those with more investment merit is by no means a perfect exercise. And it does not mean that smaller funds are uninvestable. But that step accomplishes a lot of good by weeding out many ETFs that should be ignored—typically novel ETFs that are used over short investment horizons (thematic ETFs, sector ETFs, and others designed for day trading), although some will still make it through. Eliminating those reduced the number of eligible ETFs to 461, or just 14% of the initial universe.

Most of those that remain include ETFs from some of the largest providers: Vanguard, iShares, State Street, Invesco, Charles Schwab, and Dimensional, among others. I have no plans to share that list for one simple reason: It isn’t important. This exercise was meant to show that very few ETFs meet the basic criteria to survive and thrive over the long run.

Analysis Paralysis

Admittedly, starting with the full slate of ETFs is a backward way to go about choosing an ETF. I suspect most investors start with a rough idea of what they want (value, sustainability, small caps, and so on). So, specific needs should eliminate most ETFs from consideration, though the screens discussed can still help.

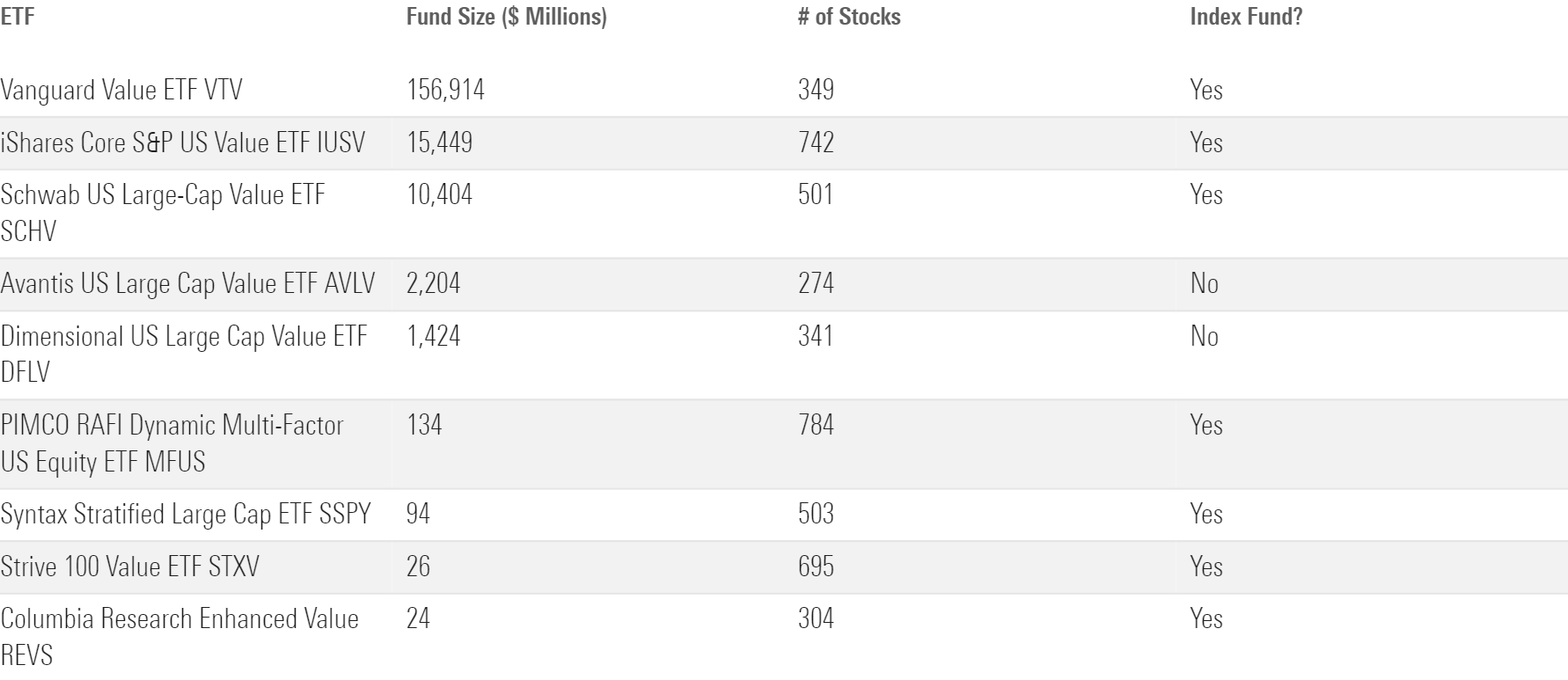

How does this work in practice? Let’s say you wanted a well-diversified US large-cap value ETF. Exhibit 1 lists nine options from the large-value Morningstar Category, and all hold hundreds of stocks. There’s a lot to unpack as each has a distinct approach. But size varies greatly, from $155 billion for Vanguard Value ETF VTV to just $19 million for Columbia Research Enhanced Value ETF REVS. From an ETF mortality perspective, your time is better spent focusing on the first five as they’re far more likely to endure.

Diversified Value ETFs

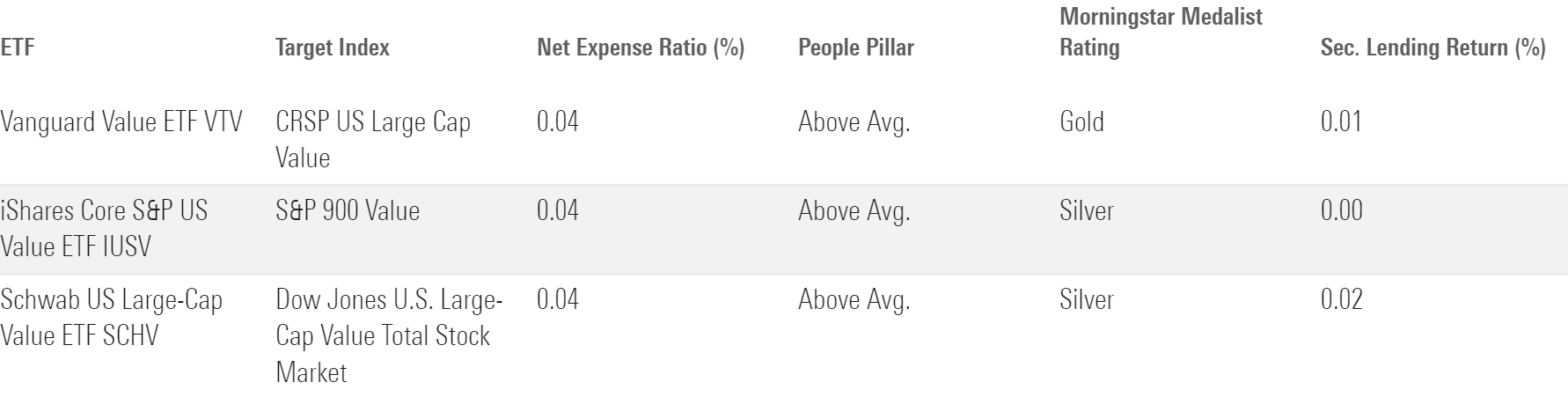

Let’s go a step further to address a question that comes to my inbox every so often. Say you wanted to further narrow down the list to index-tracking ETFs. That limits your choices to the three in Exhibit 2, and they look exceptionally similar. Each tracks a broad market-cap-weighted index, charges the same ultralow expense ratio, uses securities lending to offset those minute fees, and has a solid team working behind the scenes.

They're the Same Thing

Which one do you choose? That’s somewhat of a trick question—they’re all great. VTV looks more compelling because it has a Morningstar Medalist Rating of Gold, while the others are close behind at Silver. But the differences between Gold and Silver among broad index-tracking funds are often small. In this case, Vanguard’s ETF gets a slight edge from its High Parent rating (BlackRock and Schwab are both Above Average), but that has little impact on the performance of Vanguard’s index funds. Truthfully, it’s too difficult to discern which one of the trio will come out on top in the next five or 10 years. And any differences in future performance will likely be negligibly small and inconsistent. In such circumstances, don’t think too hard. Pick one and stick with it.

References

1 Iyengar, S.S., & Lepper, M. 2000. “When Choice is Demotivating: Can One Desire Too Much of a Good Thing?” J. Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 79, No. 6, P. 995.

2 Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. 2016. “401(k) Investment Options: Less is More.” https://crr.bc.edu/401k-investment-options-less-is-more/

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/78665e5a-2da4-4dff-bdfd-3d8248d5ae4d.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/24UPFK5OBNANLM2B55TIWIK2S4.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-25-2024/t_29c382728cbc4bf2aaef646d1589a188_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/78665e5a-2da4-4dff-bdfd-3d8248d5ae4d.jpg)