The Effect of Government Shutdowns on Equities

How to address the risks of portfolio volatility amid the ongoing debt battle.

The next deadline for a partial government shutdown is March 1. While a shutdown of the government so far has been avoided by stopgap measures, it seems likely we will shortly face another shutdown threat because the extreme faction within the House of Representatives’ Republican conference could prevent appropriations bills from passing. And if there is a shutdown, it is possible that it could last for an extended period, given the high degree of polarization and disorder in Congress. I’ve received many questions about the likely effect a government shutdown would have on equities. To answer, I think it is helpful to review the historical evidence.

Government shutdowns have occurred with a fair amount of frequency—since 1976, shutdowns have happened 20 times. Likely defying most investor expectations, the average return for the S&P 500 index during government shutdowns has been flat.

The logical explanation for the lack of much if any impact on stock prices is that investors assume any shutdown will be short-lived (because of pressures to reach an agreement), and thus, any economic impact will be muted.

The longest shutdown of the U.S. government lasted for 35 days, from Dec. 22, 2018, to Jan. 25, 2019. During that time, approximately 800,000 federal employees were furloughed or required to work without pay. Despite that, the S&P 500 rose 10.3%.

The historical evidence suggests that investors are best served by not acting on their fears. With that said, the battle over government funding this time centers on concerns over our country’s growing debt problem, which both parties have contributed to and neither party has been willing to address. The main sources of the rise in the deficit have been the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Ukraine and increases in social spending programs without funding for those expenditures. (Other sources have been cuts in individual and corporate taxes.)

To help investors understand the nature and depth of the debt problem, I’ll review the current situation, examine forecasts of the increasing size of the problem, and review the empirical research findings on the impact of a high debt/gross domestic product ratio on economic growth.

The Growing Government Debt Problem

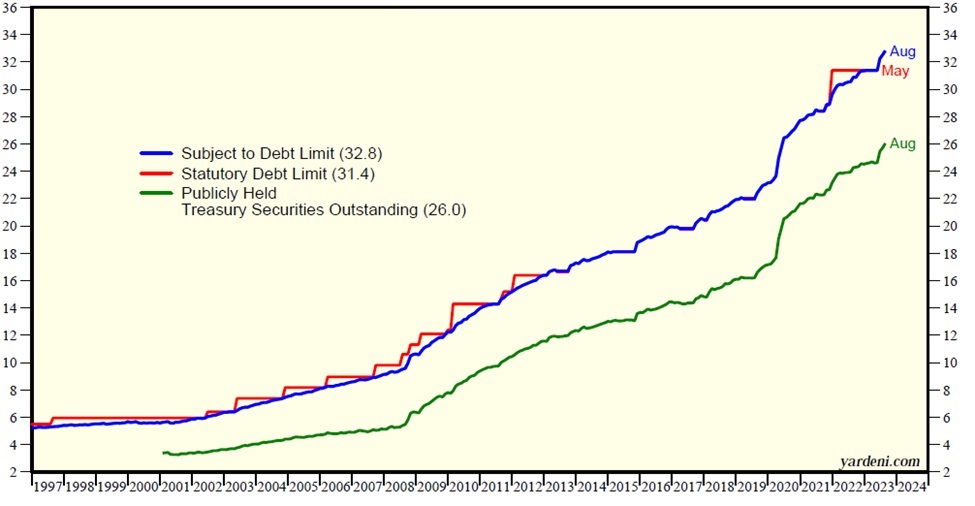

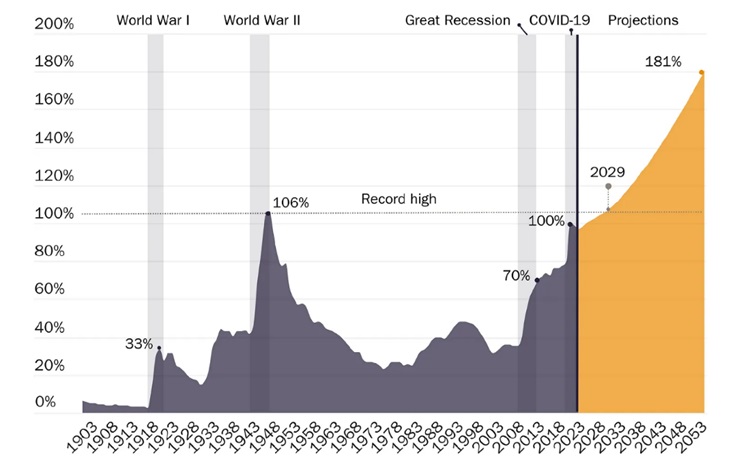

As you’ll see in the second chart below (“Federal Debt Held by the Public, Share of Gross Domestic Product”), by the end of 1999, the government debt/GDP ratio had fallen to less than 40%, the lowest level since 1973. Unfortunately, 25% of all U.S. government debt outstanding has been added just since the beginning of 2020. By the end of August, publicly held Treasury securities outstanding had reached $26 trillion.

Total Public Debt Outstanding ($ Trillions)

With higher debt levels and higher interest rates, debt servicing costs have increased from $1 billion per day in 2020 to almost $2 billion per day in 2023.

Because of the dramatic increase in interest rates, interest expense is set to rise significantly. As of Sept. 30, 2023, the average cost of the debt was 2.97%. However, current yields are much higher. With the average maturity of Treasury debt of only about six years, rising interest costs will negatively affect the debt/GDP ratio.

Adding further upward pressure on rates was the failure of the Fed to extend maturities when rates were at historic lows, resulting in 31% of government bonds set to mature over the coming 12 months.

According to the Congressional Budget Office’s latest long‐term budget outlook, publicly held debt will grow to 181% from 98% of GDP by 2053. Economic research finds that excessive public debt reduces economic growth, with damping effects kicking in when debt reaches around 78% of GDP.

Federal Debt Held by the Public, Share of Gross Domestic Product

Facts Support Fitch Downgrade

The unsustainability of the current fiscal situation led Fitch in August 2023 to downgrade the U.S. Long-Term Foreign-Currency Issuer Default Rating to AA+ from AAA. At the same time, it removed its negative watch and assigned a stable outlook. Fitch stated: “The rating downgrade of the United States reflects the expected fiscal deterioration over the next three years, a high and growing general government debt burden, and the erosion of governance relative to ‘AA’ and ‘AAA’-rated peers over the last 2 decades that has manifested in repeated debt limit standoffs and last-minute resolutions.” It also cited the underfunding of Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid (along with the aging population) and the lack of political will to address the problem.

While many criticized the downgrade, saying it was unnecessary, facts support the move: The U.S. ratio of interest payments to revenue is projected by Fitch to reach 10% by 2025 compared with a 2.8% average for the other AA rated sovereigns and 1% for the AAA rated. The simple arithmetic will become nasty if the inflation-adjusted rate on the debt rises above the economy’s underlying growth rate, which it seems likely to do. The 2023 deficit of 6.3% of GDP is an indefensible figure when the economy is at full employment—we should be running large primary surpluses, not deficits. The problematic arithmetic of rising rates on a large stock of debt is already kicking in.

The ratings downgrade itself could result in higher interest costs on our debt because of reduced confidence in our ability to repay it. In turn, that could lead to sales of Treasury debt by foreign investors, putting upward pressure on interest rates and exacerbating the debt issue, especially if the fiscal problem is not resolved. Unfortunately, the outlook is not good, as Fitch forecasts a fiscal deficit of 6.6% of GDP in 2024 and a further widening to 6.9% of GDP in 2025. These are unsustainable levels. Another problem with rising debt/GDP levels is that they would likely limit our ability to respond to future contractions in the economy with fiscal stimulus.

In summary, estimates from econometric studies of highly indebted industrialized economies indicate that the government expenditure multiplier will be positive for the first four to six quarters after the initial deficit financing and will then turn negative after three years. This implies that a dollar of debt-financed federal expenditures eventually reduces private GDP. In other words, today’s stimulus is tomorrow’s burden. Lower economic growth has negative implications for future equity returns.

Investor Takeaways

Equity markets dislike uncertainty. The battle over the growing debt burden along with the continued threat of government shutdowns likely mean there will be continued uncertainty around the problem, one that is exacerbated by the unprecedented surge in deficit spending at a time of overall growth in the economy and historically low levels of unemployment. A fierce debate will likely occur on Capitol Hill about the nation’s fiscal policies as lawmakers face a potential government shutdown and choices over trillions of dollars in expiring tax cuts. Thus, equity investors should be prepared for the possibility of increased volatility.

There are two ways to address the risks of a portfolio’s volatility. The first is to reduce exposure to stocks, longer-term bonds, and bonds with significant credit risks, while increasing exposure to shorter-term, relatively safe credit risks. By raising interest rates dramatically, the Fed has made that alternative more attractive than it has been in 16 years. For example, for those concerned about inflation, the yield on five-year Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities has increased from about negative 1.6% at the start of 2021 to about 1.87% on Feb. 20, 2024. Investors can benefit from running a Monte Carlo simulation to determine if they can lower their equity allocation, as the need to take risk in stocks has been reduced by the higher real yield available on safe bonds.

Another way is to diversify exposure to risk assets. This would include sources of risk that historically have had low to no correlation with the economic cycle risk of stocks and/or the inflation risk of traditional bonds—but also have provided risk premiums. The following are alternative assets that historically have provided diversification benefits. Alternative funds carry their own risks; therefore, investors should consult with their financial advisors about their own circumstances before making any adjustments to their portfolio.

- Reinsurance. The asset class looks attractive, as losses in recent years have led to dramatic increases in premiums, and terms (such as increasing deductibles and tougher underwriting standards) have become more favorable.

- Private middle-market lending (specifically senior, secured, sponsored corporate debt). This asset class also looks attractive, as base lending rates have risen sharply, credit spreads have widened, lender terms have been enhanced (upfront fees have gone up), and credit standards have tightened (stronger covenants).

- Consumer credit. While credit risks have increased, lending rates have risen sharply, credit spreads have widened, and credit standards have tightened.

- Long-short factor funds.

As Kevin Grogan and I demonstrated in our book, Reducing the Risk of Black Swans, adding unique risks has historically reduced the downside tail risk associated with conventional stock and bond portfolios.

The views expressed here are the author’s. Larry Swedroe is head of financial and economic research for Buckingham Wealth Partners, collectively Buckingham Strategic Wealth, LLC and Buckingham Strategic Partners, LLC.

Larry Swedroe is a freelance writer. The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/8c5d95ea-6364-418e-82fc-473134024ece.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HBAEAVIJHFEBTPMEK2UMVQ3NFQ.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/8c5d95ea-6364-418e-82fc-473134024ece.jpg)