For Income Investors, Bond Yields Are Looking Attractive

While it could be a bumpy ride, bond yields are at their highest levels in many years.

Are bonds a good investment right now?

It seems like a tough sell. This year is well on its way to being the worst in modern history for bond investors. But there is a significant silver lining: there is finally some income to be earned in the fixed-income market.

In that sense investors can thank the Federal Reserve, even though it is the central bank’s aggressive inflation-fighting interest-rate increases that have been the cause of double-digit losses across many bond investments in 2022.

Bond Investing Math

What’s at work is the basic math of investing in bonds. Prices and yields move in opposite directions. And in 2022, there has been a massive decline in prices across the entire market. That’s led to a huge rise in bond yields.

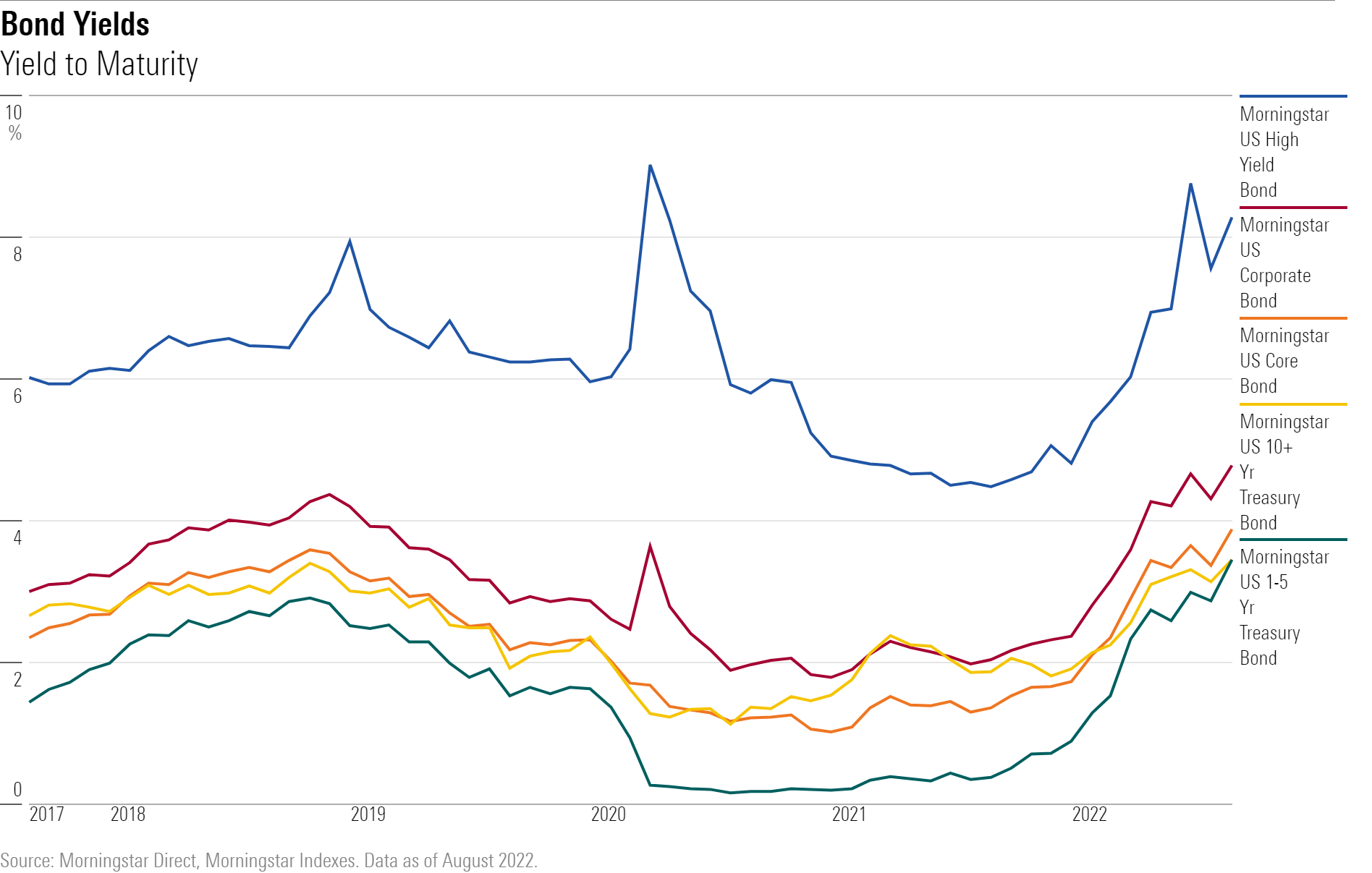

Just a year ago, a U.S. Treasury 2-year note was yielding a measly 0.2%, while 10-year Treasury notes were around 1.3%. Taking on more risk with your investment didn’t earn you much: Investment-grade corporate bonds—debt issues by quality companies —earned you just north of 2%, and high-yield bonds, aka junk bonds, around 4.6%.

Today, U.S. Treasury 2-year notes earn 3.80%, 10-year Treasuries 3.4%, corporate bonds 4.8%, and high-yield debt north of 8.0%. And for high earners in high-tax states, municipal bonds can offer tax-free yields around 4% on high-quality funds.

“There’s a lot out there to choose from,” says Kathy Jones, chief fixed income strategist at Charles Schwab. “You can build a portfolio with a 5% yield with relatively low credit risk and not that much (interest rate) risk, and for a lot of people that makes sense.”

The caveat for investors is that if inflation remains stubbornly high, as the August Consumer Price Index report showed, it may well be that the Fed will continue to raise interest rates even higher than is currently expected. That in turn could cause further losses for bond investors.

But, Schwab’s Jones says, “we’re not playing for capital gains. It’s the income.”

A Record Bad Year for Bonds

While investors are probably well aware of how bad 2022 has been for stocks, from a historical perspective, it’s been even worse on the bond side of their portfolios. Many corners of the bond market are posting their biggest losses on record. (Stocks are down, but even at these levels, there have been worse selloffs.)

For example, Vanguard Total Bond VTBIX—the largest U.S. bond fund—is down more than 12% in 2022. That’s the fund’s biggest loss since it was launched in 1995. Another fund with a top track record is the Pimco Income PIMIX. This wide-ranging bond fund’s 7.8% loss is on track for its worst annual performance since its inception in 2007.

“Its been a historic year. Its been an exhausting year,” says Anders Persson, chief investment officer for global fixed income at Nuveen. “There’s not quite the appreciation for how big a downdraft that we have seen.”

The catalyst, of course, has been the surge in inflation, which in turn has prompted one of the most aggressive series of Fed rate hikes in history. The Fed, which usually moves in small, cautious steps, has raised the federal-funds rate from zero at the start of the year to a current target of 2.25 to 2.50%. This tightening of monetary policy included two 0.75 percentage point increases, the first such moves since the Fed began targeting the federal-funds rate to set monetary policy in the 1990s. The last time the Fed was this aggressive in raising rates was during the high-inflation years of the early 1980s.

Hopes for a Fed Pivot Fade

In recent months there had been some hopes that inflation would begin to decline from its highest levels in four decades, and that the Fed would be able to pivot to smaller increases, starting with its next policy announcement on Sept. 21, and finish the year with the funds rate at a 3.5% to 3.75% target rate. With those hopes, bond yields began to creep down from the highs set in June.

But with the August CPI report showing inflation still stuck at very high levels, expectations swung back to another three-quarter point increase this week, with the Fed taking the funds rate to 4.25% to 4.50% by the end of the year. And with that, the bond market swooned again, taking yields to new multi-year highs.

“The expectation was that we have seen peak inflation and it would be starting to come down,” says Schwab’s Jones. “While it probably has peaked, it’s not coming down as quickly as we had expected. That, combined with talk about the Fed going to 4%-plus (on funds) is dragging bond yields up.”

Critically for investors, even though inflation readings have been disappointing, there also is a belief that the Fed is acting so aggressively that eventually inflation will come under control—even if it is at the expense of recession.

“The bond market is pretty confident—as are we—that this inflation problem is not a long-term problem,” says Rob Waldner, fixed income chief strategist at Invesco.

In fact, says Waldner, the bull case for bonds is that the Fed is raising so aggressively that they will be forced to reverse course sooner rather than later.

(Find Morningstar’s view on why inflation will fall in 2023, click here.)

Goodbye TINA, Hello Bond Yields

The rise in bond yields marks a significant change in the income investing landscape that has largely existed since the 2008 global financial crisis. In the years that followed, the Fed kept interest rates at extremely low levels, just as the central bank did in the wake of the pandemic recession.

The acronym TINA—which stands for "there is no alternative"—was applied to the dilemma facing investors. With short-term interest rates locked by the Fed at close to zero, investors needing to earn meaningful returns had essentially no choice but invest in stocks.

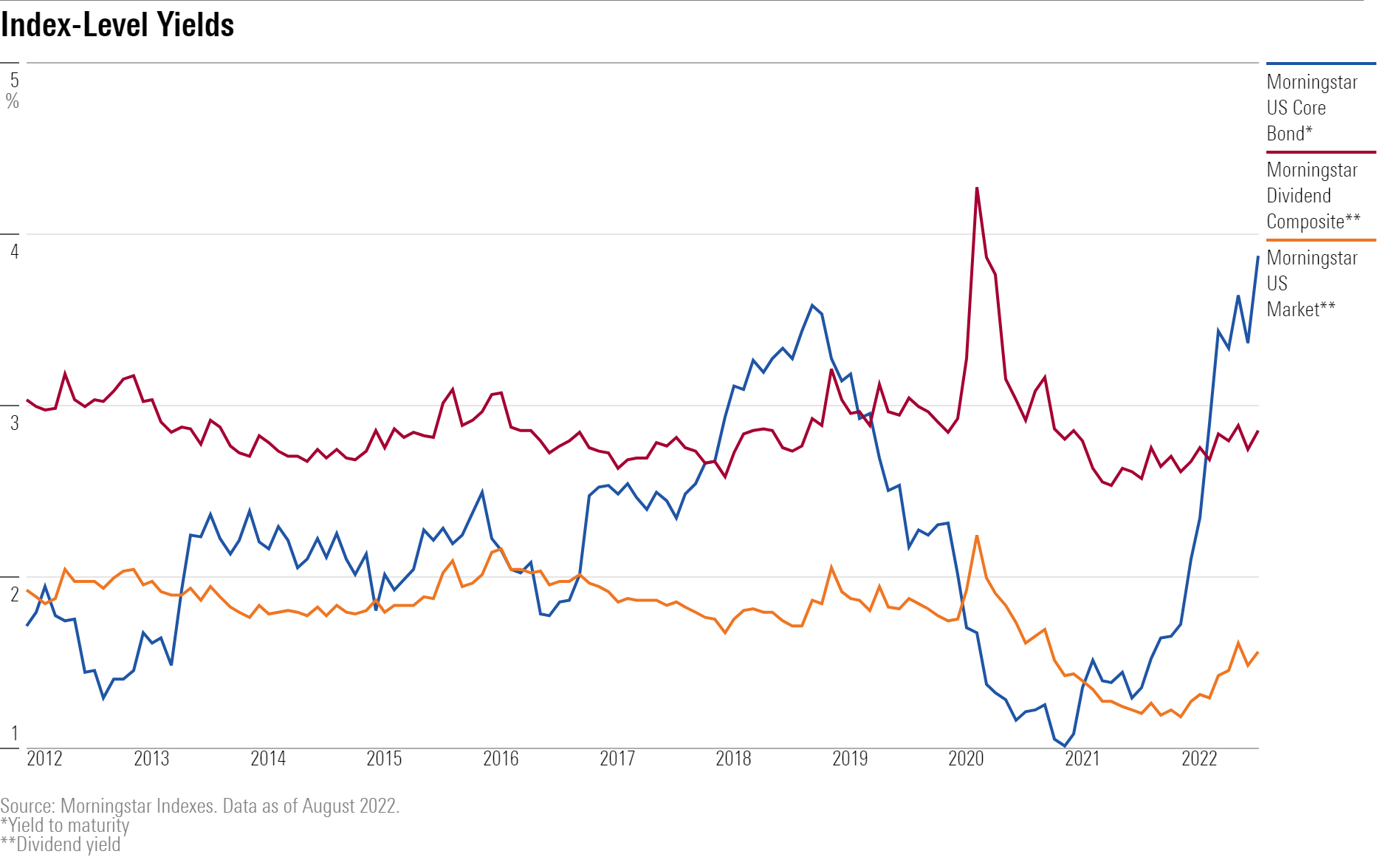

Even before the pandemic, income investors could earn more in bond yields with a dividend strategy than was offered by a broad bond market strategy, like the ones reflected by the Morningstar US Core Bond Index. In the fall of 2019, the Core Bond Index yielded roughly half a percentage point less than the Morningstar Dividend Composite Index and last September, the dividend index offered a yield that was more than a percentage point higher than bonds. Plus, there was the potential for growth on the investment from the appreciation of stock prices.

But that dynamic has reversed in dramatic fashion since late 2021, even before the latest jump in yields. The yield on the Morningstar Core Bond Index was nearly 3.9% at the end of August, while the Morningstar Dividend Composite Index was yielding 2.9%.

Bond Yields on the Rise

It’s not just compared to stocks that bonds are now looking more attractive. Bonds are also looking better when inflation expectations are factored in.

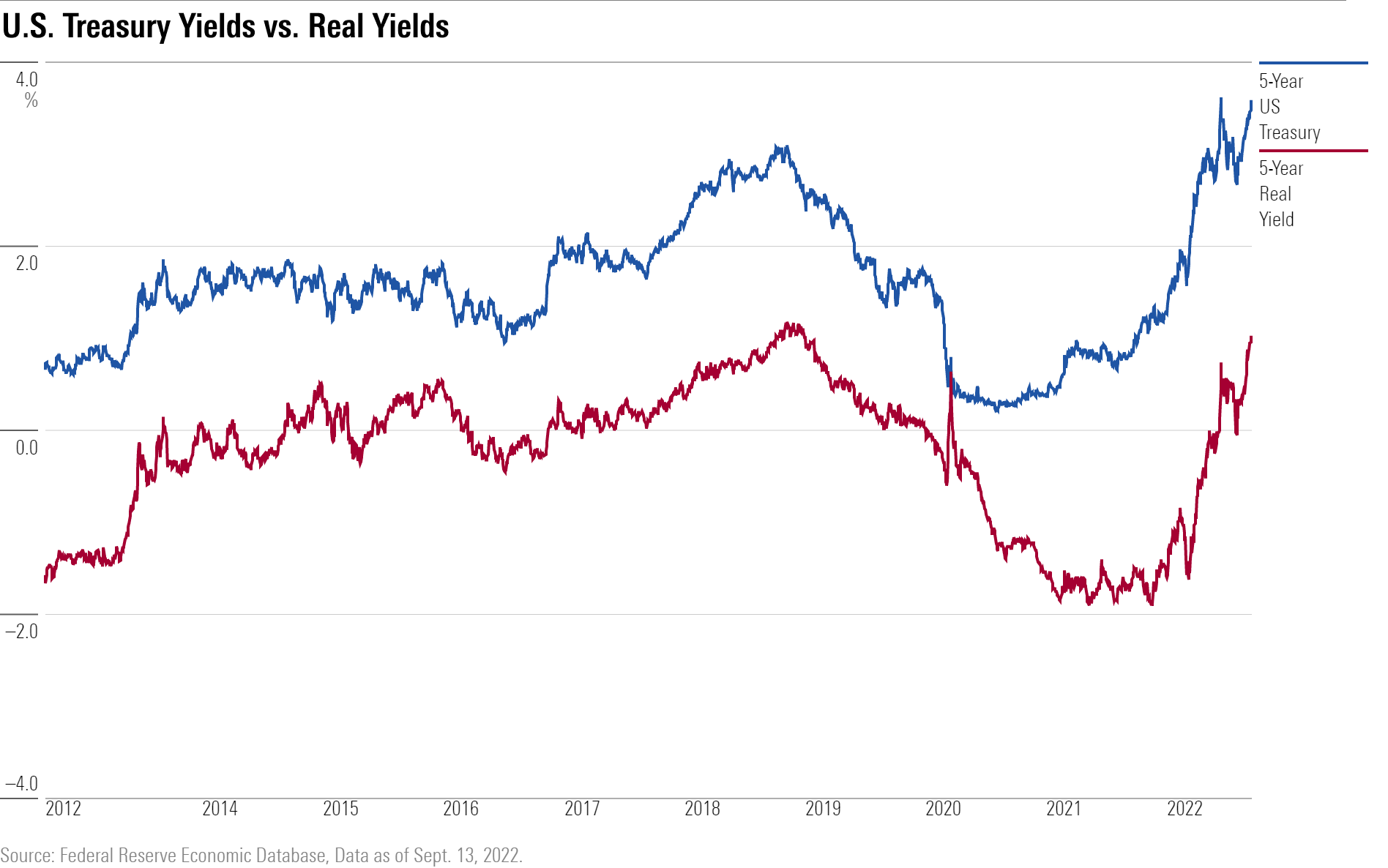

With the fixed payouts that come with bonds, inflation can erode the value of those income streams. That’s why many in the market pay close attention to so-called real yields, which are yields minus the impact of inflation.

Real yields on 5-year Treasuries were meaningfully negative or essentially zero for much of the time from 2011 through 2016, and then again starting in 2020 when the Fed pushed rates to zero and flooded the financial system with cash to support the economy during the COVID-19 lockdown. In other words, when inflation was factored in, investors were losing money on their bond investments.

But now, real yields have turned meaningfully positive, approaching their highest levels of the past decade. “That’s a pretty attractive proposition,” says Schwab’s Jones.

Invesco’s Waldner says real yields are even more in attractive when looking at high quality corporate bonds. “You’ve got investment grade yielding more than 5%,” he says. “That’s something on the order of a 2 ½% real yield when 18 months ago investment grade was returning less than inflation.”

Expect a Bumpy Ride

While bonds have already seen a significant selloff, market participants caution that the coast isn’t yet clear if inflation doesn’t begin to recede at a faster pace.

Overall inflation as measured by the CPI hit a high of 9.1% in June and had been expected to fall to 8.1% in August. However, for last month the CPI registered 8.3%. More worrisome to the bond market was that the so-called core CPI—which excludes often volatile food and energy costs—rose to 6.3%. That was its second-highest reading of the year.

Persson says the expectation at Nuveen is that inflation has hit its peak, but the uncertainty around the Fed’s ability to get inflation down toward its 2% target could be “problematic for the bond market.”

“The concern is stickiness as some parts of CPI, particularly around rents,” says Nuveen’s Persson. “Our simplistic view has been that going from 9% to 5% (inflation) is going to be relatively easy…but getting from 5% to 2% is going to be much, much harder.”

As was seen in the latest selloff in the bond market, the longer inflation stays high, the more expectations will build that the Fed will have to push interest rates up. In that environment, bond prices would be under downward pressure, leading to continued losses in bond funds.

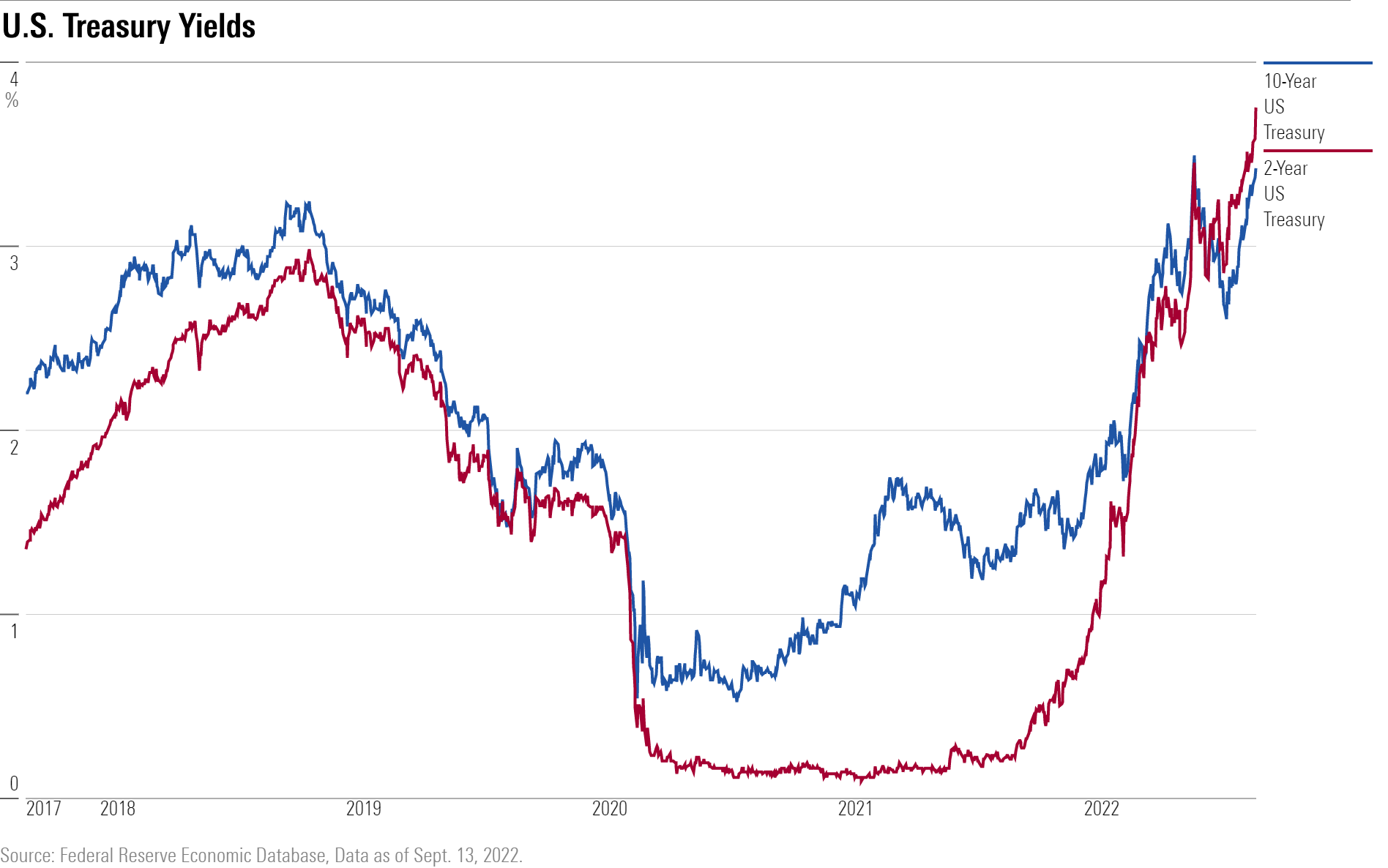

In addition, in that environment, short-term yields would likely rise even further above longer-term yields, a dynamic known as an inverted yield curve. Inverted yield curves have often been a precursor to a recession.

Should expectations for a recession build even more, that could put downward pressure on longer-term government bond yields. “There’s going to be a tug of war between the probability of a soft landing versus a recession hard landing that continuously impacts the bond markets,” Persson says.

Where to Invest in Bonds Now?

Christopher Alwine, head of the global credit team in the fixed income group at Vanguard, notes that such a back and forth around the possibility of a hard landing versus a soft landing will create a slightly different dynamic in the corporate bond market, where a recession would make it tougher for corporate bonds to perform as well as more interest-rate sensitive government bonds.

“That puts us cautious on credit,” which includes markets such as corporate bonds, Alwine says. However, “we’re looking to be opportunistic where the market either gets too pessimistic on recession risk or too optimistic on a soft landing.”

That said, “if you’re looking to put money to work, by historical standards we’re looking at some pretty high levels of yield across the market, especially on credit,” Alwine says. “You might not like your near-term price return on your funds, but we're at a point in yields that they can actually help cushion some of the volatility from new money being put to work,” he says.

“We believe bonds are back, in that regard,” Alwine says.

One factor working in favor of corporate bonds, including high-yield bonds, he says, is that debt levels across the economy are healthy. Often in a recession, the concern is that the economic slowdown will make it harder for bond issuers to keep up with their debt obligations.

“The strains that you would typically see late in an economic expansion aren’t present this time,” Alwine says. “Household balance sheets are healthy, corporate balance sheets are healthy. We see that in investment grade, we also see that in high yield, as well, where the credit quality of high yield is better than its been. And so that provides a cushion in terms of a period of economic weakness.”

Alwine says they also see emerging market bonds as attractively priced. “They’re on the cheap side, but it’s cheap for a reason,” he says. Emerging markets are particularly vulnerable to a strong U.S. dollar—such as is the case now—and weakening economic growth. “While there will be challenges in emerging markets, it’s an area where we see opportunities.”

At Invesco, Waldner says the bias is also to favor higher quality bonds, such as investment-grade corporate and municipal debt.

“In munis the fundamentals are very solid,” he says. Waldner is wary of bonds with lower credit quality, such as bank loan or high-yield debt that could suffer during a recession.

Nuveen’s Persson says that given the potential for continued volatility investors shouldn’t try to “go all in” on any single corner of the bond market. But one area they favor is preferred bonds, which are generally issued by financial institutions. “They have quite an attractive yield, especially on an aftertax perspective,” he says.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ed529c14-e87a-417f-a91c-4cee045d88b4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GJMQNPFPOFHUHHT3UABTAMBTZM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZYJVMA34ANHZZDT5KOPPUVFLPE.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/LDGHWJAL2NFZJBVDHSFFNEULHE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ed529c14-e87a-417f-a91c-4cee045d88b4.jpg)