Why Your 60/40 Balanced Portfolio Isn't Working in 2022

For the last two decades, bonds and stocks usually haven't moved in the same direction. That's not the case this year.

One of the tried and true ways to cushion a portfolio from wide swings in the stock market is to take a slug of your money and invest in bonds. But chalk up 2022 to being one of those rare times when investing in bonds doesn’t work the way it usually does.

This approach is often referred to in the Wall Street shorthand of a 60/40 balanced portfolio: 60% stocks and 40% bonds. There are endless variations to the stock/bond ratio and their underlying investments. But some version of a 60/40 portfolio usually does a good job of protecting portfolios from the kinds of wild swings that can lead to making bad decisions, such as dumping stocks just as the market is bottoming.

The reason the 60/40 portfolio has usually worked is that stocks and bonds haven't been moving in the same direction over an extended period of time. There may be days or weeks when they both rise or both fall—or bonds fall a little while stocks fall a lot—but for most part, they haven't been trading in lockstep. So when a financial plan requires stability, there’s good reason to invest in bonds.

But this year has been the worst in history for many bond funds. At the same time, stocks have fallen into a bear market. In fact, this year is only the second time in over four decades that stocks and bonds both posted losses for two consecutive quarters.

The result: investors who seek safety in the 60/40 balanced portfolio have been disappointed.

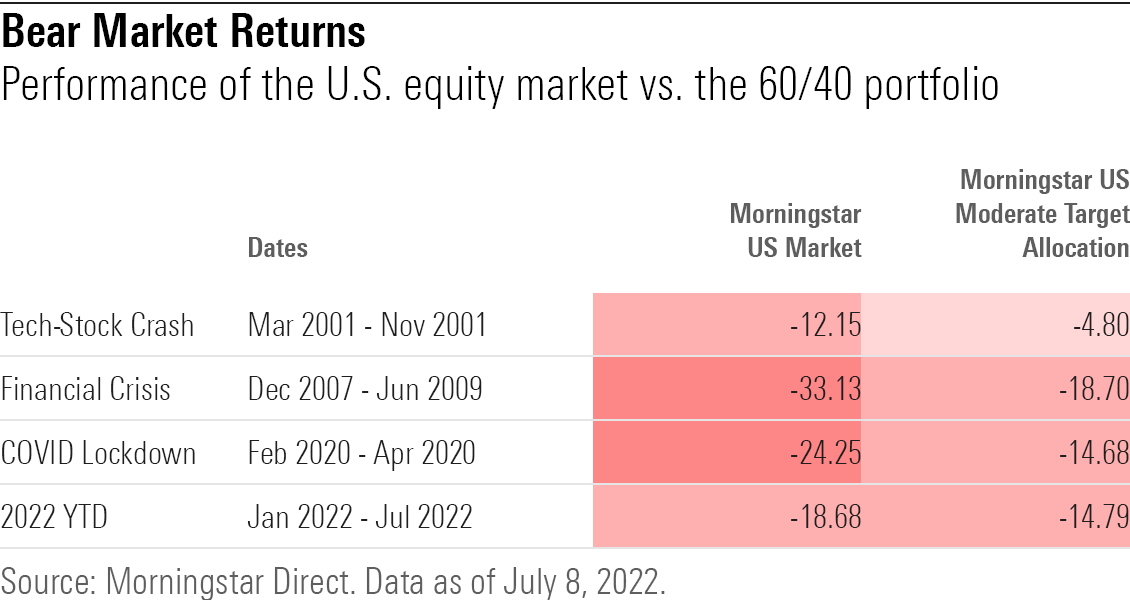

The Morningstar US Moderate Target Allocation Index—a diversified mix of 60% equities and 40% bonds designed as benchmark for a 60/40 allocation portfolio—lost 14.8% through July 8. That wasn't far behind an 18.7% decline in the stock market, as measured by the Morningstar US Market Index.

Investors today are discovering a fact of the markets: While some relationships among investments may appear steady, trends come in and out of favor or even reverse for long stretches of time.

“Diversification has served investors well historically, but investing isn’t like physics,” says Dan Lefkovitz, strategist at Morningstar Indexes. “Just because a certain relationship has been in place for many years doesn’t make it an immutable law.”

Why Invest in Bonds?

Bonds can serve as a shock absorber when things aren’t going well in the stock market. In particular, U.S. Treasury bonds can offset or mitigate losses on stock holdings and also smooth out the volatility that comes with stock investments.

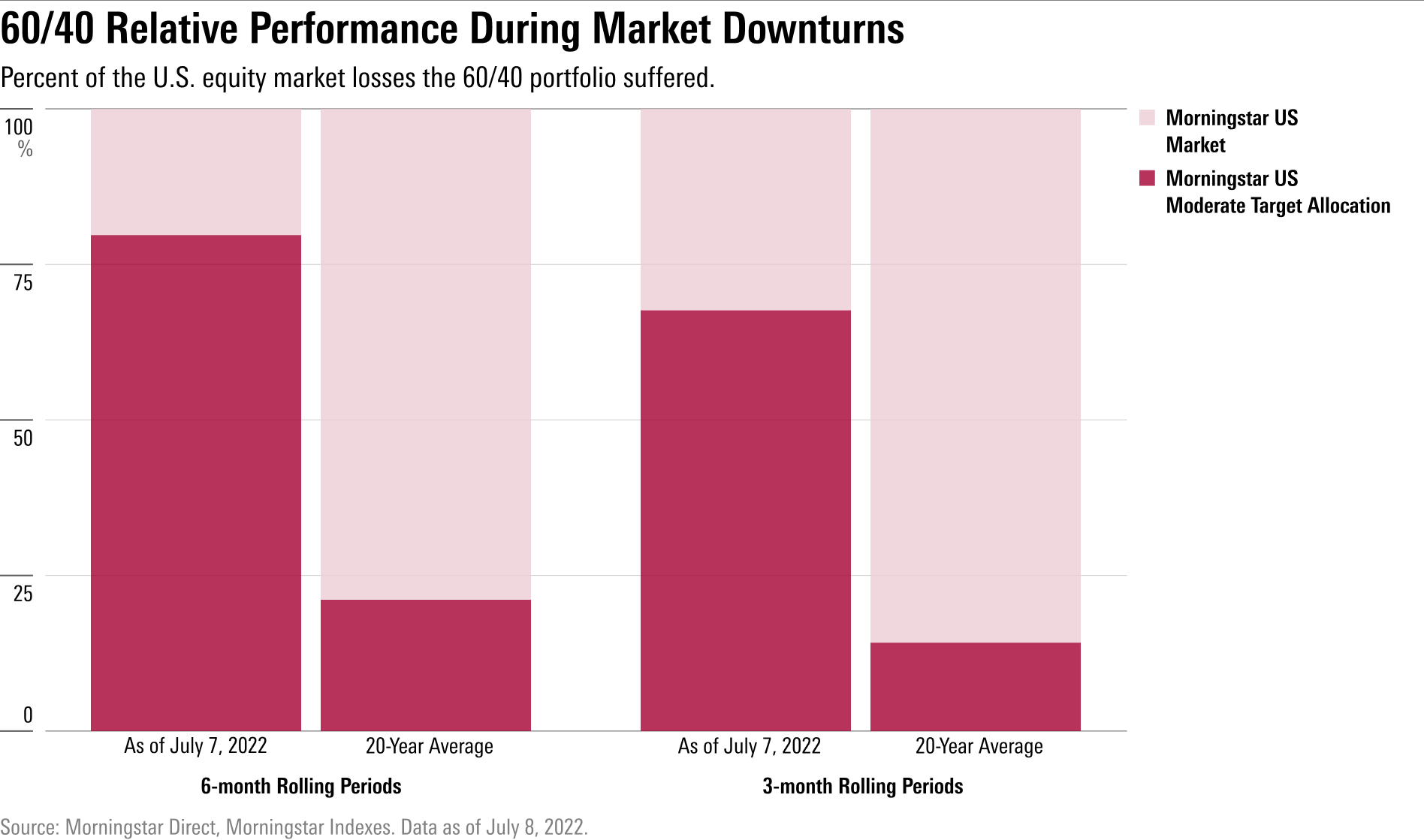

One way to measure this is to look at the percentage of stock market losses taken by a 60/40 balanced portfolio during periods of stock market declines. (This is sometimes called downside capture.)

For the last 20 years leading up to the second quarter, the Morningstar US Moderate Target Allocation Index posted losses equaling just 14.2% of the stock market’s declines in the average three-month rolling period. For six-month periods, the 60/40 balanced portfolio registered declines that were 20% of those in the stock market.

For example, during the dot-com crash of 2001, the Morningstar US Moderate Target Allocation Index had a downside capture ratio of 39.5% from peak to trough, helping investors stay afloat. And during the brutal bear market of the 2008 financial crisis, a 60/40 portfolio saw roughly half of the losses seen in stocks.

But it’s been a different story in 2022.

For the six months ended July 8, the 13.5% decline on the Morningstar US Moderate Target Allocation Index has equaled 79.7% of the equity market’s losses. For the past three months, the balanced portfolio has suffered losses equaling 67.6% of the stock market.

Do Bonds and Stocks Move Together?

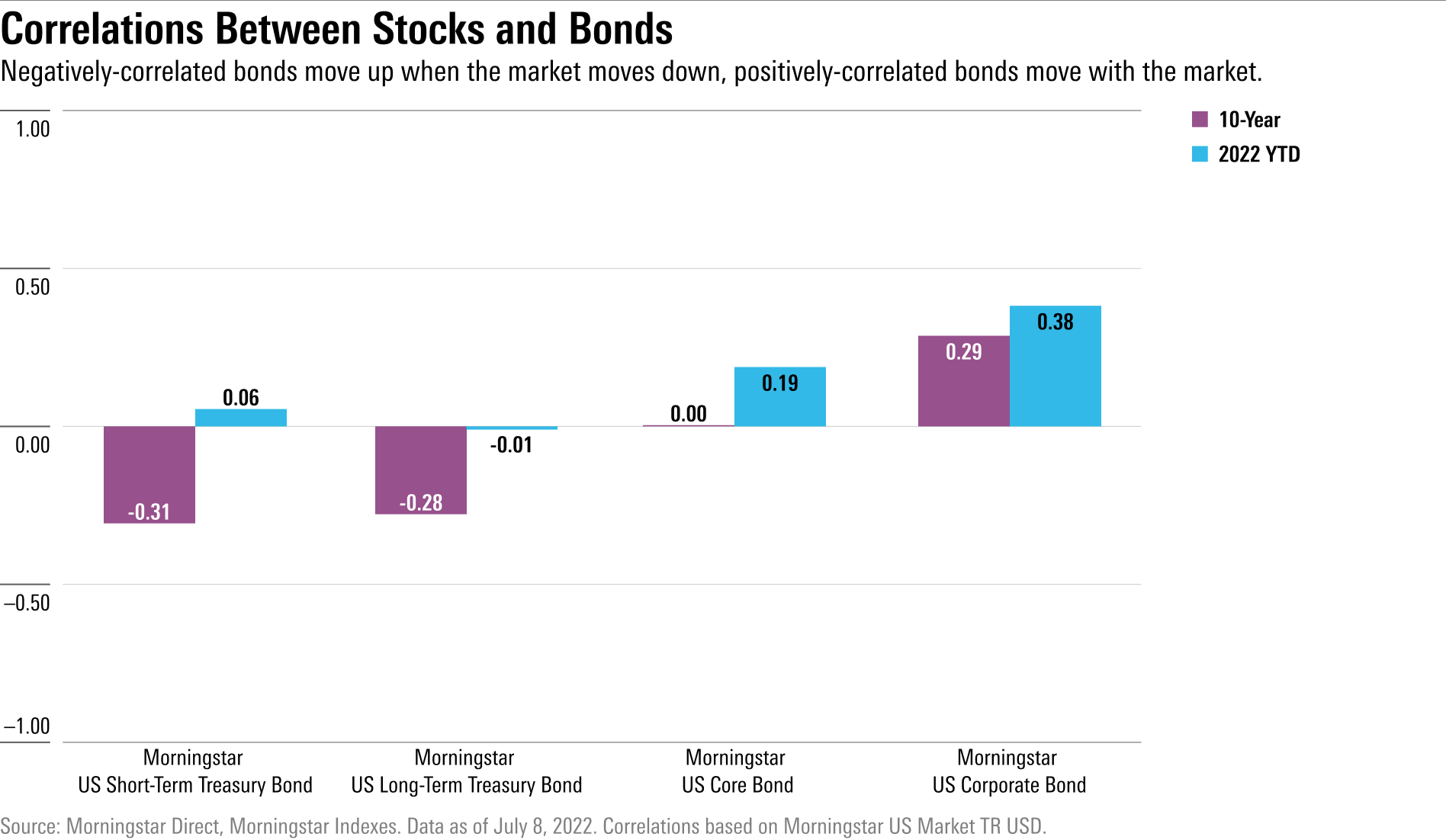

The most common way to look at the relationship between bonds and stocks is a statistic known as correlation. Correlation measures the tendency of different investments to move up or down at the same time. When measuring correlation, a reading of 0 indicates stocks are moving with no relationship, while 1 means gains or losses in perfect unison. A reading of negative 1 means they uniformly move in the opposite direction.

Over the past couple of decades, some—but not all—corners of the bond market have moved inversely to stocks. That’s especially true of long-term U.S. Treasury bonds.

The Morningstar US 1-5 Year Treasury Bond Index has an average 10-year correlation of negative 0.31 to the Morningstar US Market Index. This implies that short-term Treasury bonds will rise when U.S. stocks fall, with moderate likelihood. Long-term Treasury bonds also showed a moderate negative correlation with U.S. stocks.

This year, however, the correlations have shifted. Short-term Treasury bonds have been positively correlated with U.S. stocks for the year to date, and long-term Treasuries have effectively shown no relationship. Correlations between stocks and corporate bonds have jumped up by 30%.

“The fact that stocks and bonds have been in sync so far in 2022 has caught a lot of people off guard,” Lefkovitz says.

To some extent, investors shouldn’t be all that surprised. The relation between bonds and stocks has changed over time.

AQR Capital Management's Portfolio Solutions Group noted that in the last 20 years, bonds have often been able to provide positive returns when stocks fell. "But go back a bit farther, and history tells a different story, one in which a negative stock/bond correlation has been the exception, not the rule." In the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, stocks and bonds had a positive correlation, AQR says.

Why Hasn’t Diversification Worked This Time?

“Usually, instances that were bad for equities were related to a growth shock or a recession,” says Philip Straehl, global head of research at Morningstar Investment Management. “As a result of that shock, you’d have stocks underperform, but bonds provided a ballast.”

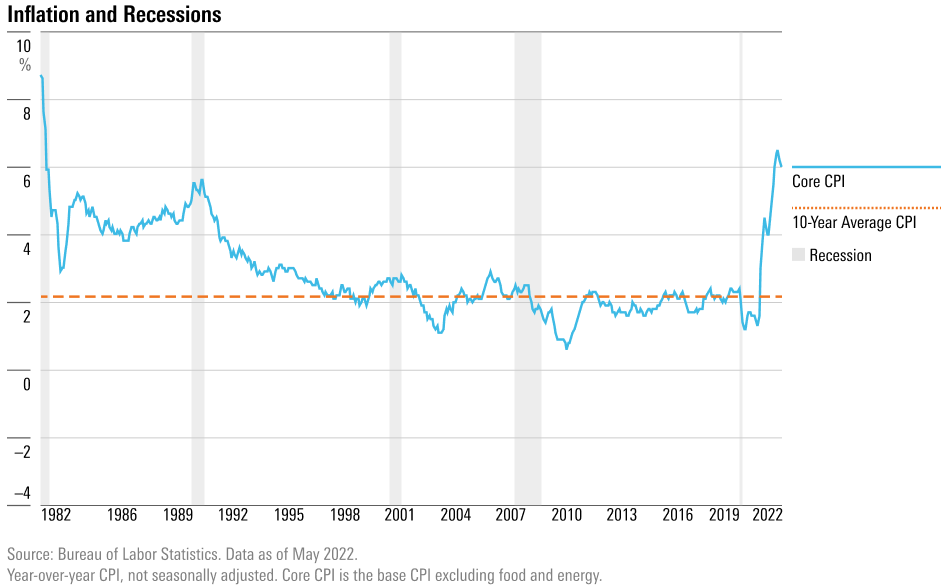

Inflation has been heating up around the globe over the past year. The U.S. Consumer Price Index rose 9.1% from year-ago levels in June, the largest 12-month increase since December 1981. Rising prices were driven mainly by gasoline, shelter, and food.

“Times of high inflation are not good for either bonds or stocks,” Straehl says. “Both assets have a discount rate—if there’s a spike in inflation, usually that leads to an adjustment in valuations across both equity and fixed-income markets.”

As the AQR analysts summarized, “Stocks and bonds have been stronger diversifiers when growth news dominates and weaker diversifiers when inflation news dominates.”

Does Diversification Still Work?

“We can’t expect the relationship between stocks and bonds will always hold—correlations bounce around,” Lefkovitz says. “But just because in a six-month period it hasn’t worked, this doesn’t undermine the validity of the 60/40 portfolio. Diversification has served investors well for a long time.”

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ba63f047-a5cf-49a2-aa38-61ba5ba0cc9e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/URSWZ2VN4JCXXALUUYEFYMOBIE.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/CGEMAKSOGVCKBCSH32YM7X5FWI.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ba63f047-a5cf-49a2-aa38-61ba5ba0cc9e.jpg)