A Better Way to Look at Investing in Equities for Income

The pros and cons of using dividend-paying stocks as bond replacements.

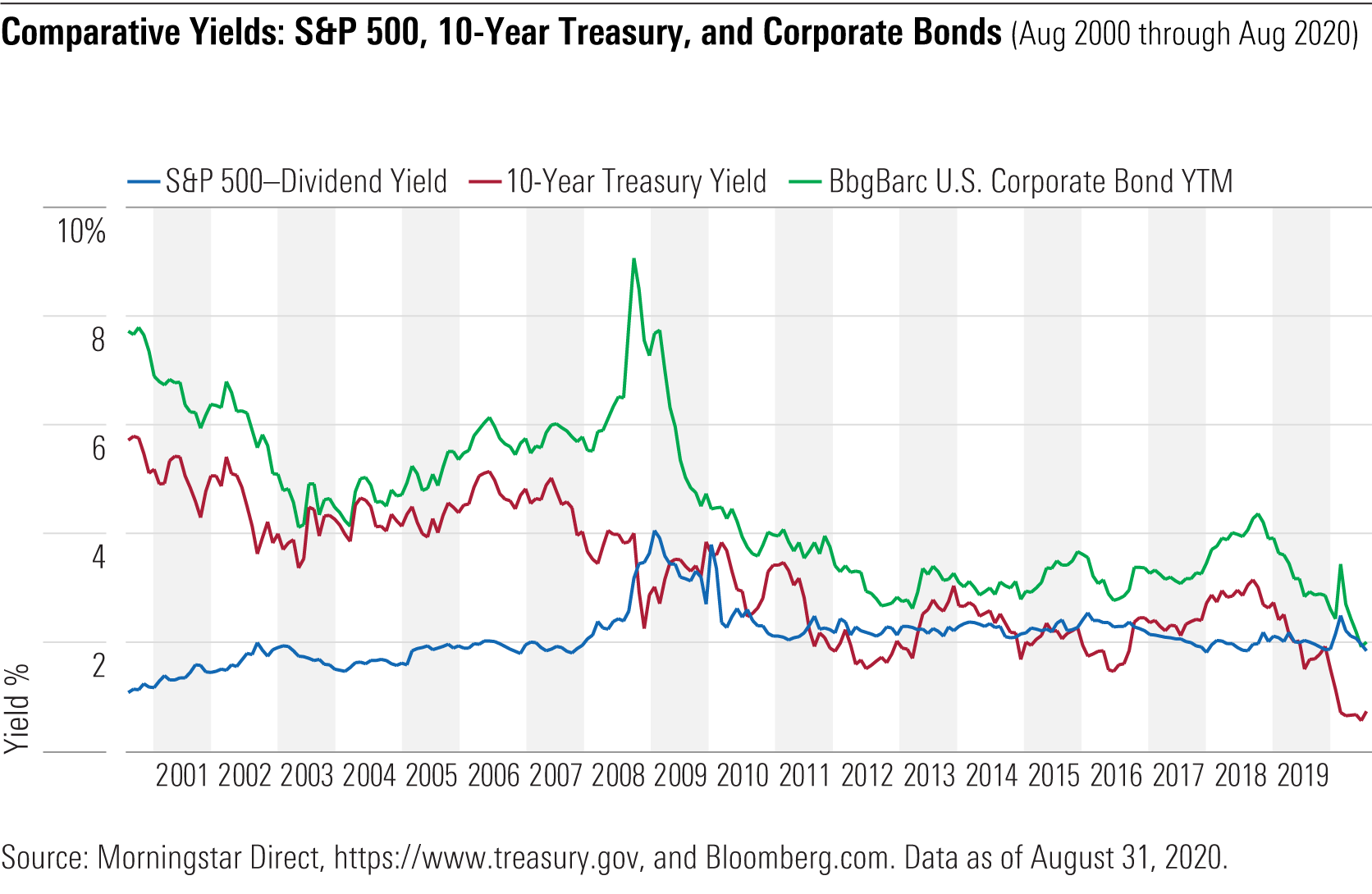

It's tempting for investors striving to live off their portfolios in the current interest-rate environment to consider dividend-paying stocks as bond replacements. While equities have historically been 4 to 5 times more volatile and lack the protection afforded fixed-income securities in the capital structure, their yields offer an enticing alternative.

Stock yields are lower now than at the end of the financial crisis, but they're better than 10-Year Treasuries and competitive with corporate bonds. In fact, the relative advantage of the S&P 500 hit a more than 20-year high in July, when its 1.96% projected one-year yield was about 3.6 times the 10-Year Treasury's 0.55% yield and edged the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Corporate Bond Index's 1.91%.

Traditional ways of measuring stock portfolios' yields have their shortcomings, though. The Morningstar Equity Style Factor Dividend Yield data point used for the S&P 500 in Exhibit 1 assumes each stock in a portfolio will continue to pay dividends at recent rates, which doesn't always happen and ignores fund fees. The 12-Month (or TTM) Yield metric takes fund fees into account, but it is a backward-looking estimate whose accuracy diminishes in extreme conditions. [1]

Even when yield measures are spot on, they can disappoint if viewed in isolation. A fund with a projected yield of 4% suggests it would return $4 for every $100 invested. It could still hit that yield target if market tumult cut both its dividend payment and asset base in half, but an investor would be poorer for it.

It is better to focus on income generation itself in the context of total return and tax efficiency. Using the methodology of the new Income Analysis tool within Morningstar Direct, we'll do that here. Although there's no way to predict the future, comparing several funds' payouts over different time periods can help investors make informed choices and have reasonable expectations.

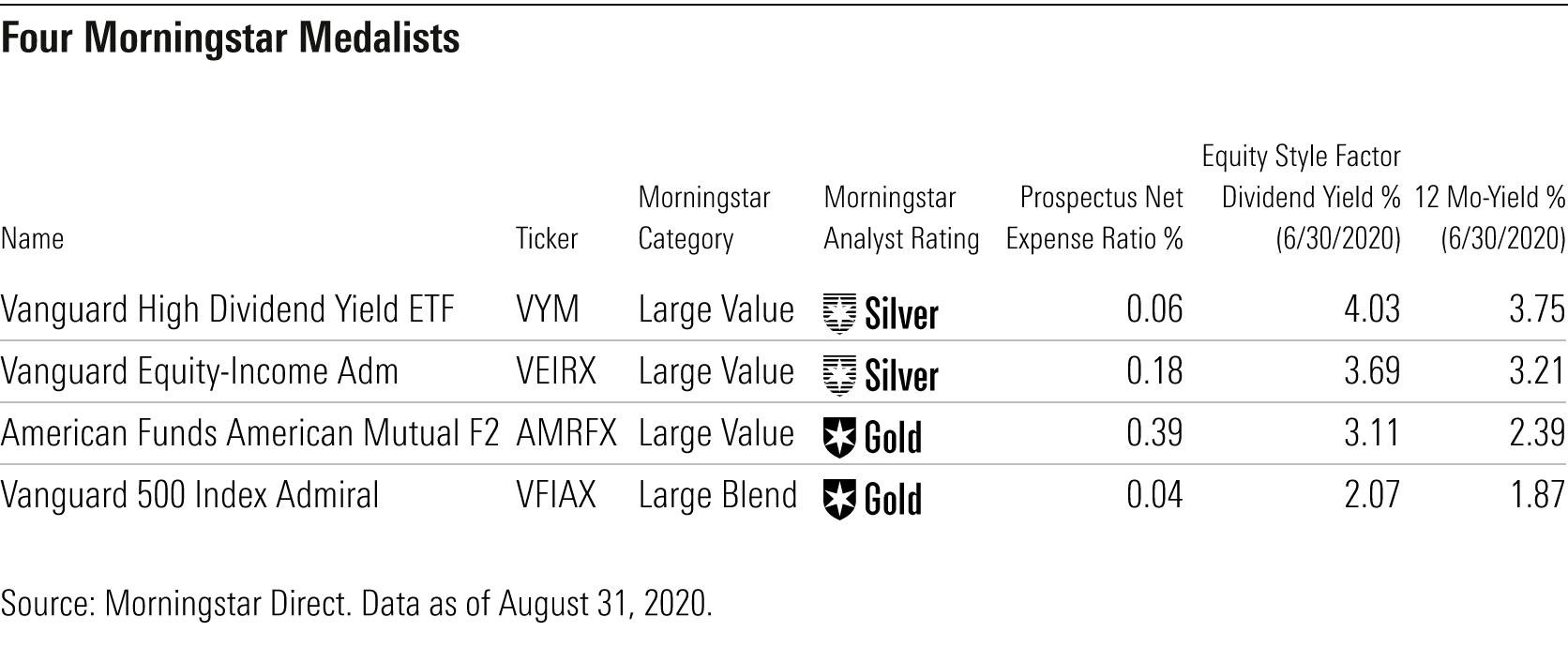

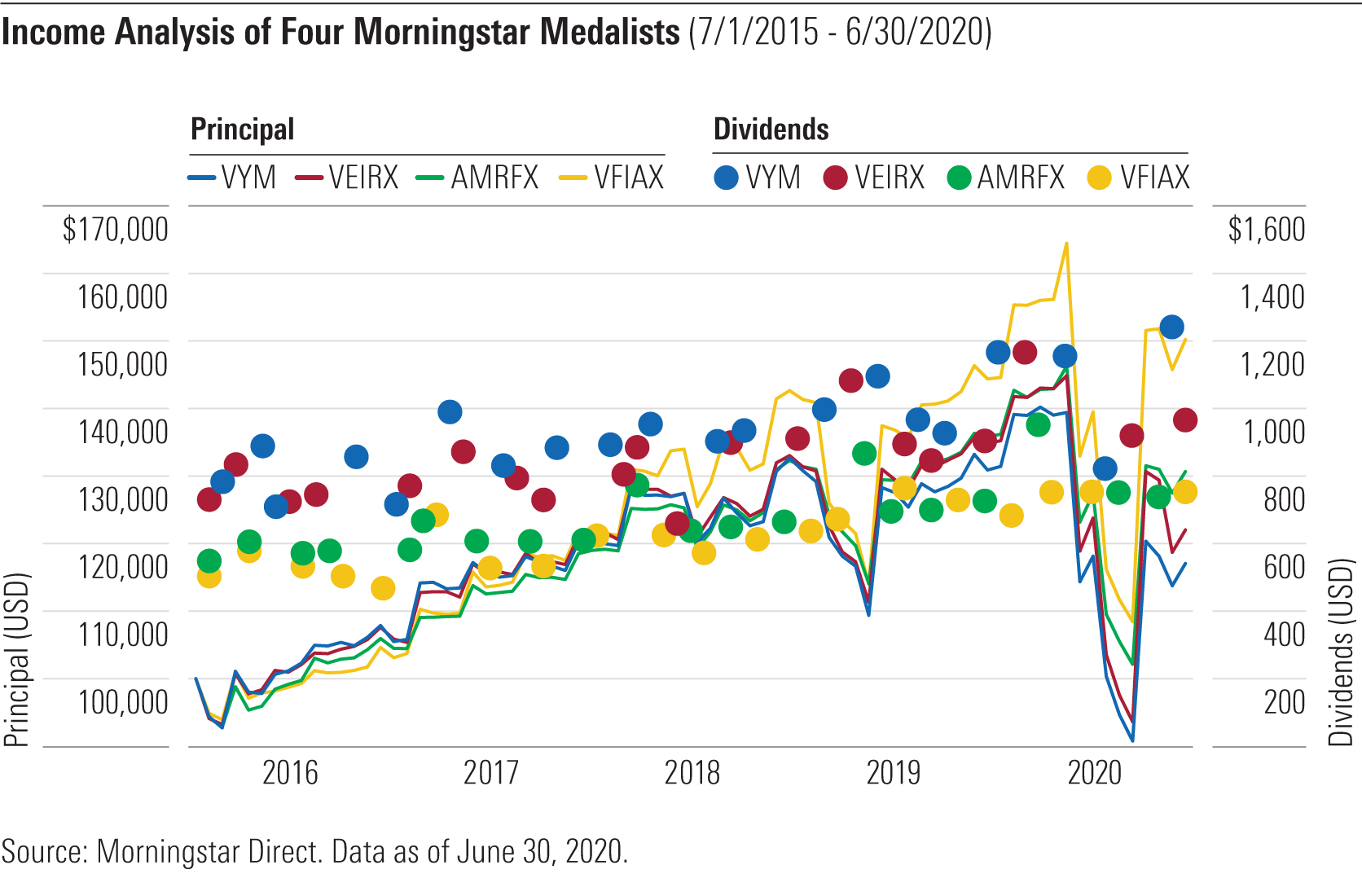

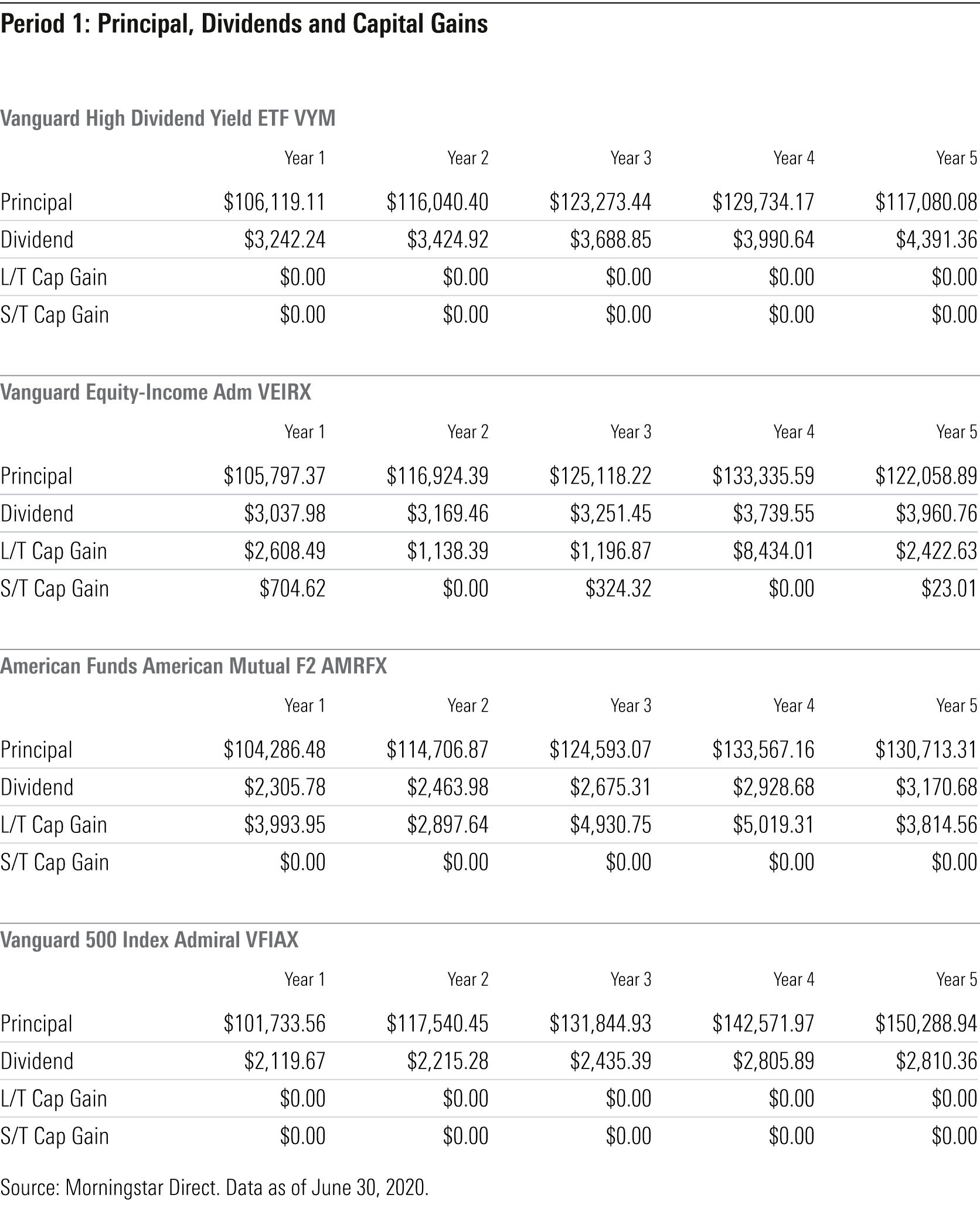

Four Funds in Five Years Exhibit 2 highlights two active and two passive no-load Morningstar Medalist funds that are viable options for income-oriented investors. Exhibit 3 then shows what would have happened if an investor put $100,000 of principal in each and reinvested capital gains but received dividend payments from July 1, 2015, to June 30, 2020, a five-year period that included two corrections and a sharp bear market.

Vanguard High Dividend Yield ETF VYM typically paid the biggest dividend each quarter, but its principal grew the least. Meanwhile, Vanguard 500 Index VFIAX usually paid the smallest dividend, but its principal grew the most. In fact, each fund exhibited a trade-off between current income and subsequent return, which illustrates one danger of chasing yield.

Even for those who prioritize total return, turning to equities for income requires a significant appetite for risk. A Vanguard 500 Index investor on Feb. 19, 2020, for example, had pocketed $11,013.19 in total dividend payments over the preceding three-plus years and still had nearly $164,600 of principal to earn more income. The investor's principal, however, dropped 34% to less than $108,500 at the market's March 23 bottom before rebounding to about $150,200 by the end of June. Holding on would have been hard for many living off equity income.

Investors who stomached the ride did well in all four funds, as Exhibit 4 shows. The initial $100,000 of principal rose between 3.20% and 8.49% per year while paying substantial and growing dividends. At 6.86%, Vanguard Equity-Income VEIRX had the lowest dividend-growth rate, but that still beat inflation.

Receiving dividend cash payments put a dent on total return, though. Each fund's annualized principal growth was between 2.2 and 3.5 percentage points less than its total return. That shows how much reinvested dividends contribute to total return. [2]

The comparison in Exhibit 4 also highlights the tax efficiency of the passive strategies over their active counterparts. Vanguard High Dividend Yield and Vanguard 500 Index didn't distribute any capital gains, while Vanguard Equity-Income and American Funds American Mutual AMRFX paid $16,852.33 and $20,656.21 in respective total capital gains.

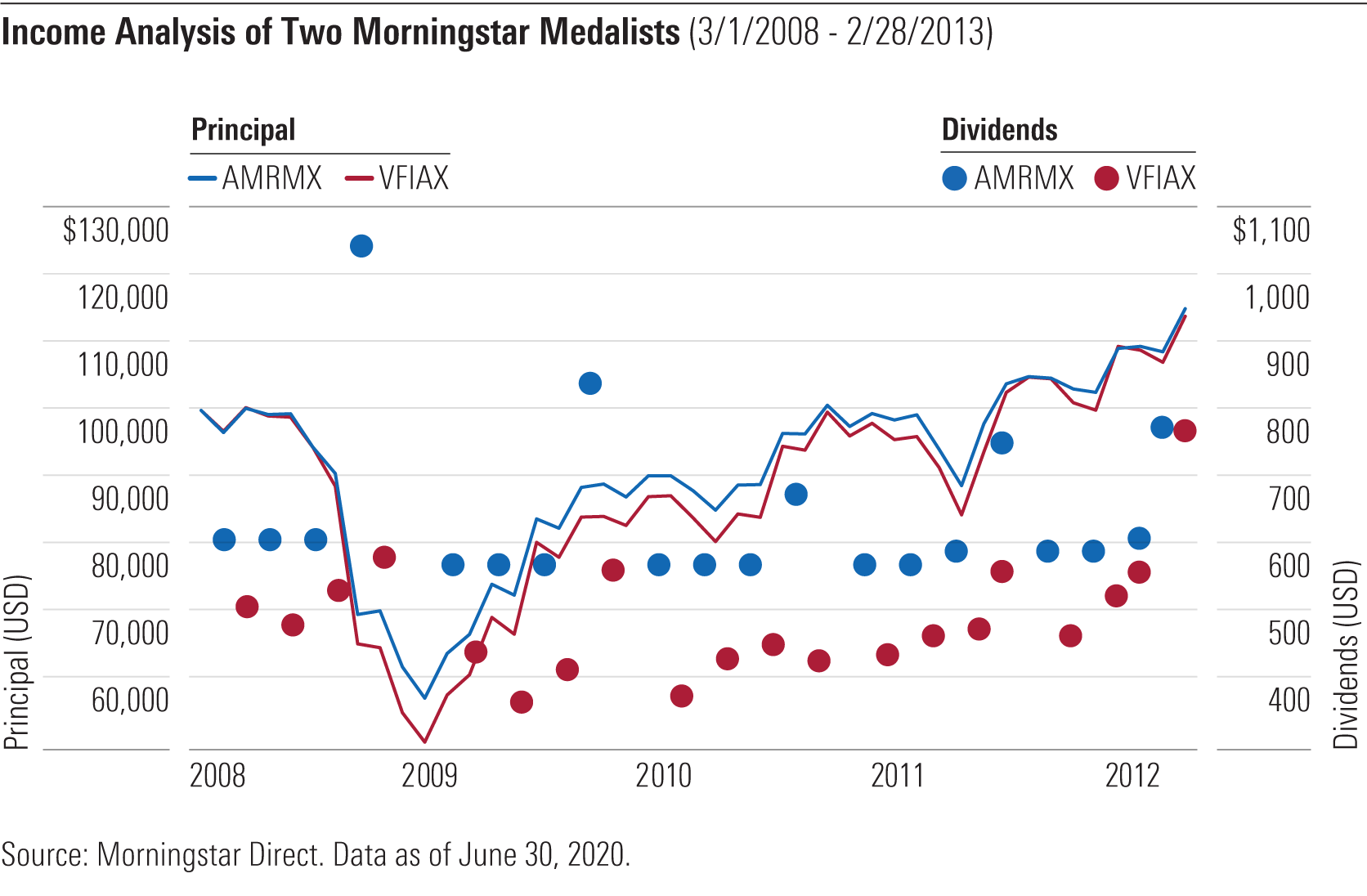

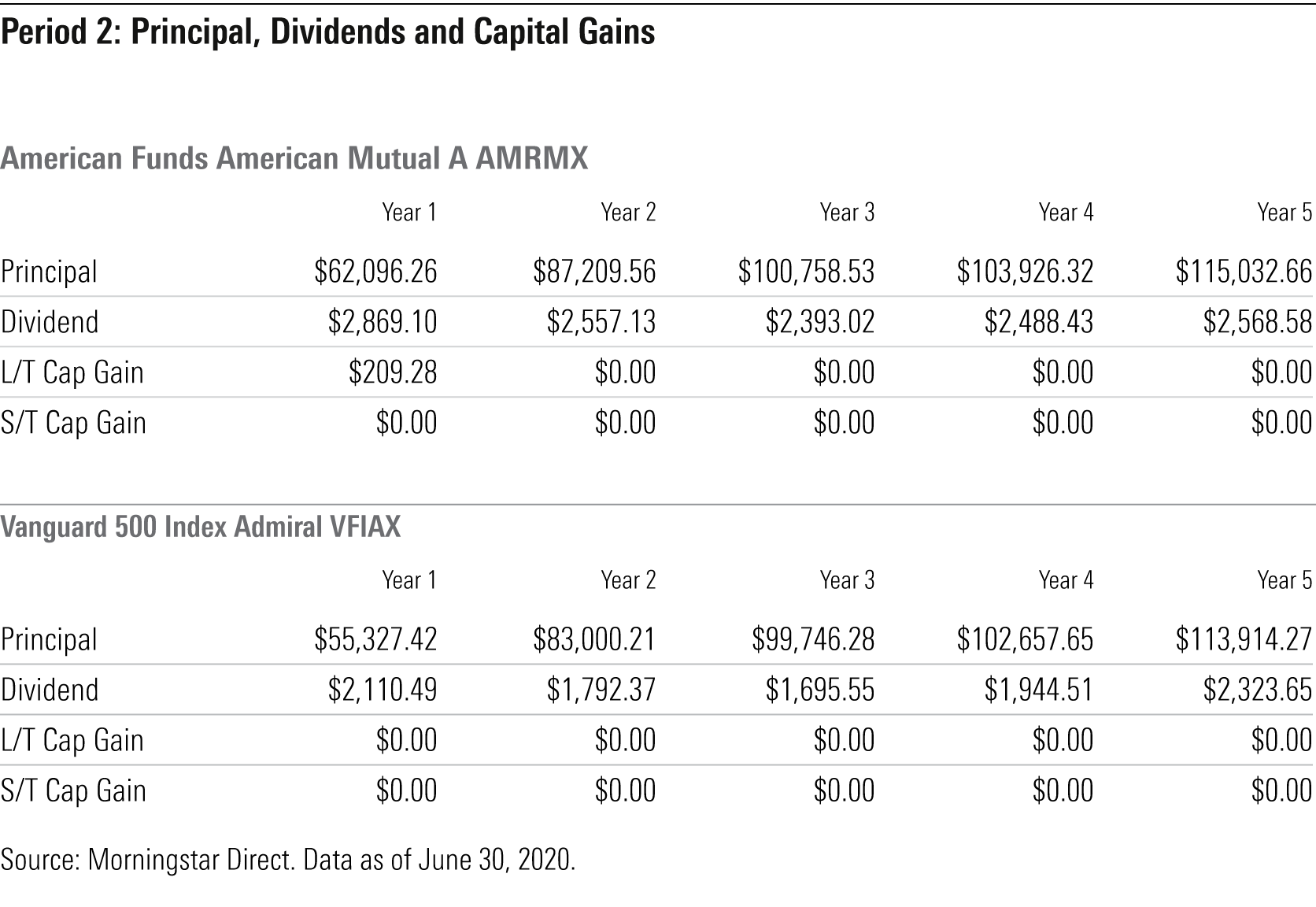

Two Funds in Another Five-Year Period For investors who can afford lower dividend payments, Vanguard 500 Index and American Funds American Mutual emerged as the best two options in the first period, with the nod going to Vanguard 500 for its superior overall return and tax efficiency. But a severe bear market early on changes the picture. The S&P 500 began the five years ended on Feb. 28, 2013, with its worst 12 months in more than 50 years, losing 43.3%. That ominous start gave an advantage to American Funds American Mutual's consistently resilient portfolio. A $100,000 investment in its A shares grew more and paid bigger dividends. [3]

American Funds American Mutual also nearly matched Vanguard 500 Index's tax efficiency. In turbulent times, active managers can sometimes dull market-cap-weighted index funds' tax edge by harvesting losses to offset gains.

More important than which fund fared best, however, is that both provided attractive results over the whole five-year period ended Feb. 28, 2013, following a historically disastrous start. It took roughly three years in each case for the principal to recover, but investors earned dividend income as they waited.

Tilting the Odds in Your Favor These examples reinforce the promise and peril of turning to equities for income. Investors who use dividend-paying stocks as bond replacements must be prepared to withstand significant principal loss. Breaking return into its components--principal, dividends, and capital gains--over a multiyear period while keeping in mind each fund's typical attributes, especially its downside protection, can help clarify potential risks and improve the odds of success.

Endnotes [1] The TTM Yield data point is calculated by adding together a fund's per-share dividend payments over the prior year and then dividing that amount by the fund's most recent month-end net asset value, adjusted by adding back any per-share capital gains payments over that year. It can produce inflated yield estimates in sharp downturns, such as the 12-month period ended Feb. 28, 2009. The data point says that Vanguard 500 Index's 12-month yield was then 3.81%, when it was actually 2.11%, a difference of 170 basis points.

[2] Recognizing the importance of reinvested dividends to total return serves as an antidote to what Samuel M. Hartzmark and David H. Solomon have called the "free dividends fallacy": investors' tendency to relegate dividends and capital appreciation into separate mental accounts as if they're disconnected attributes. See the Aug. 30, 2018, version of their "The Dividend Disconnect" research piece.

[3] Exhibits 5 and 6 substitute American Funds American Mutual's older A shares (AMRMX) for its F-2 shares, which did not exist at the beginning of the second five-year period.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/08b315db-4874-427f-b3b1-f2b84a16e609.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/FGC25JIKZ5EATCXF265D56SZTE.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-25-2024/t_d30270f760794625a1e74b94c0d352af_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DOXM5RLEKJHX5B6OIEWSUMX6X4.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/08b315db-4874-427f-b3b1-f2b84a16e609.jpg)