How Rising Interest Rates Affect Financials Stocks

Financials sector investors must navigate interest-rate uncertainty.

The U.S. Federal Reserve announced Nov. 2 that it would increase the federal-funds rate 75 basis points to a range of 3.75%-4%, and it is widely expected to go higher in December and in 2023. The financials sector is particularly sensitive to interest rates, and a higher, lasting rate environment would benefit those companies with positive exposure to rising interest rates.

However, there is a material chance of the United States going into a recession over the next couple of years that could be accompanied by accommodative monetary policy, which would lower interest rates and cloud some of these firms’ prospects.

To gain some clarity, I spoke with Morningstar Research Services’ director of financial services equity research Michael Wong. Our discussion reflects conditions and valuations as of Sept. 30. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Laura Lallos: Why is this a particularly challenging interest-rate environment for investors?

Wong: Inflation and interest rates are closely tied together, and the drivers of inflation in the U.S. and the rest of the globe can be different. There’s a lot of discussion about whether inflation is transitory or whether it’s more core. One of the main drivers of core inflation that people are looking at is wages. This is a little bit more particular to the U.S., where wages for the past couple of quarters have heated up a bit more than the rest of the globe. Part of the reason the interest-rate environment is so challenging is because the inflation environment is challenging, and there are many different drivers of inflation across the globe.

What makes it especially hard for investors trying to figure out how inflation and interest rates tie into their investment strategy, whether it’s with bonds or stocks, is that expectations feed on themselves, and government monetary policy can often confuse the situation. For example, many people expect that interest rates could fall in the back half of 2023. But there are two completely separate reasons interest rates might fall: because the economy is doing extremely poorly, or because the economy is doing well.

The first scenario would be that the Fed or monetary authorities across the globe raised interest rates too much and, therefore, have to cut interest rates in order to help the economy. On the other hand, let’s say the Fed raises interest rates just enough and creates a soft landing that brings down the rate of inflation. It doesn’t have to have restrictive monetary policy of extremely high interest rates, so it decides to lower. Those two scenarios have different implications for stocks and investing. If interest rates fall because we’ve entered a recession, that could be bad for risk assets. If interest rates fall because the Fed was successful in having an economic slowdown without a recession, that’s totally different for stocks.

Lallos: Why are financial services stocks particularly sensitive to interest rates?

Wong: Interest-rate-related revenue is a core part of the earnings stream or the business of many financial services companies. Outside financial services, the most material way that companies are affected is the interest rate that they pay on their debt.

Banks are the most obvious. They receive interest on their loans and also on the fixed-income securities and mortgage-backed or other asset-backed securities that they hold on their balance sheet when they have more deposits than they can find profitable opportunities to loan out for. Then they also have it as part of their core operations, like the interest they pay on their deposits. What interest are they gaining on their loans? What interest are they gaining on the investments on their balance sheet when they have excess deposits? And what are they paying on their deposits?

Then you have insurance companies. People who follow Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway know that insurance companies make money from investing the float in the time between when they collect those premiums and when they pay out. So, insurance companies are heavily influenced by the return that they gain on their investment portfolio, which is determined largely by interest rates.

And then we have asset managers that have money market funds, like Federated Hermes. In a zero-interest-rate environment, the company has to waive a lot of fees. But once interest rates start coming back, it will have a material uplift in revenue.

Lallos: What should investors hoping to profit from rising rates consider?

Wong: Banks are a somewhat obvious beneficiary of rising interest rates; lately they’ve seen earnings increase quite a bit. That said, one thing to watch out for over the next couple of years is higher credit costs as they normalize. During the pandemic, credit costs went extremely low, somewhat surprisingly. Because of government stimulus, people were saving massive amounts of money because they had fewer things to spend on. Services consumption went extremely low, and there’s only so many goods you can buy. Some people had income replacement from unemployment that was higher than their regular wages. There was a moratorium on paying interest on student loans and on mortgage payments in some cases. People were able to build up their savings, and because they were saving a lot of money, they were not defaulting on their loans. As a result, credit costs at the banks went far below normal, even lower than during economic expansion periods.

Higher interest rates are going to help the net interest income of banks, but there will be a somewhat countervailing effect as credit costs increase. That said, it’s not going to be really bad. We’re going from abnormally low to something a little bit more normal, which is higher than what it has been over the previous couple of years. Most people are not forecasting that we’re going to get into a severe recession with high unemployment rates and relatedly high credit costs.

I would note that if you’re looking for companies that will benefit from rising interest rates, you should look for companies with low deposit betas. You’re also looking for companies that are asset-sensitive, which means their interest-earning assets reprice faster than their interest-bearing liabilities. If interest rates were to increase 100 basis points, and a bank’s costs of funding or what they pay on deposits were also to increase 100 basis points, that would be a deposit beta of 100%. But if interest rates increase 100 basis points, so that the rate they’re charging on loans increases 100 points, but the amount they pay on deposits only increases 25 basis points, that means their net interest spread increases 75 basis points.

A bank with a low deposit beta may be a core banking franchise that has a lot of checking accounts relative to savings accounts or certificates of deposit. That’s because people seek out a high interest rate on savings, while checking accounts usually pay nothing or almost nothing.

Lallos: Do financial companies disclose their level of interest-rate sensitivity?

Wong: Interest-rate sensitivity disclosures are not standardized and have their limitations, but they are still a reasonable first step in ranking relative exposures to changes in interest rates. The most common disclosure by financials firms is the effect on net interest income of a 100-basis-point increase in the interest-rate yield curve compared with a baseline scenario. For firms with both large wealth-management and investment banking segments, the effect on total revenue from a 100-basis-point rate increase is relatively small, frequently in the low-single-digit percentage points, so we don’t expect significant benefits from rising rates.

Lallos: What other factors do you look at when assessing interest-rate sensitivity?

Wong: Business models. There are differences in the business model of an online bank versus a traditional bank, for example. Why do people go to online banks? Because for the most part, they pay the highest interest rate. People go to traditional banks because maybe they want to visit a physical branch once in a while or because they see the marketing of the physical branch there. So online banks generally have a higher deposit beta. They have to increase the amount they pay on deposits along with increases in the federal-funds rate or the overall interest environment at a higher rate than traditional banks do.

Among investment-services firms, there are differences between an online brokerage and a wealth-management firm. An online brokerage will typically have a lower deposit beta. If you sign up for an online brokerage like Charles Schwab or E-Trade, you’re doing so primarily because you want to invest in stocks or bonds or mutual funds. If you have any cash in your account, that’s cash that is waiting to be invested. It’s not like a certificate of deposit that is going to be locked up for three or five years, where you’re looking for the highest interest rate.

Wealth-management firms have different client group demographics. These are usually higher-net-worth individuals than the typical brokerage account customer. If you have low-single-digit thousands of dollars in your brokerage account, whether you’re getting paid 0.2% or 0.5% is probably not going to matter too much. But if you’re a high-net-worth individual, and you have maybe $100,000 in cash, tens of basis points might start to matter. If you have a financial advisor who’s actively managing your account, they are looking to get as much return as possible for you.

Lallos: In a recent white paper, you named Charles Schwab as a top pick for rising interest rates and noted that Goldman Sachs is less rate-sensitive. What are the key differences that account for this?

Wong: Business mix matters a lot. More than 50% of Charles Schwab’s net revenue is related to interest rates in one way or another, so rate changes have a much greater effect on its overall business. Goldman Sachs’ interest revenue percentage is around 10%.

Going back to the business model, Charles Schwab is a brokerage; about half of its business is online brokerage. (The other half is supporting Registered Investment Advisors.) The customers with all those brokerage accounts are relatively interest-rate-insensitive, because they’re not looking at the rate paid on their cash.

I think that Charles Schwab still has quite a bit more to go in its net interest income story and its growth. There’s the short end of the yield curve and the long end of the yield curve. Charles Schwab will benefit from the rise in short-term interest rates immediately. That’s already started to flow into its net revenue.

But Charles Schwab also has a banking business with a lot of ABS, like residential MBS, that will take a longer time to reprice. I think the average duration on its bond portfolio or MBS portfolio is 4.0-4.5 years. So, roughly speaking, around 10%-20% of the portfolio matures every year, and Schwab can then take that cash and reinvest it. That means that the benefit from higher interest rates will play out over multiple years, because that’s related to the long end of the interest-rate yield curve, and because as a portion of the portfolio matures, Schwab can reinvest at a higher rate.

Lallos: How does Goldman Sachs’ business model compare?

Wong: Goldman Sachs has Marcus, its online bank, and it gains deposits by paying a fairly high interest rate. That means its deposit beta is higher, so it won’t keep as much of the increasing interest rates as Charles Schwab will. Also, some other deposits come from corporate clients, which tend to be more active in gaining the highest rate that they can get on their cash balances. So, business mix and business model are two differences. But note that even though Goldman Sachs is relatively rate-insensitive for a financial services company, most companies in almost every sector outside of financial services would be relatively interest-rate-insensitive.

Goldman Sachs, like other investment banks, faces headwinds. Investment banking and trading revenue was abnormally high in 2020 and 2021 and should normalize lower over the next couple of years, which will offset much of any benefit from higher interest income. That said, we believe much of this normalization is already factored into the stock’s price. The company is only modestly interest-rate-sensitive, so not much of its valuation is dependent on interest rates climbing and remaining high. In the medium term, the market may reward the company for initiatives that should improve the stability of its earnings, such as its push into consumer banking and changes in its investment-management business.

Lallos: You’ve singled out LPL Financial as another company that benefits from rising rates.

Wong: The thing about LPL Financial is that a very large portion of its interest-rate sensitivity is just to the short end. LPL may have some of the highest exposure in the near term to higher interest rates. LPL would be for people that have a very strong view of higher short-term interest rates, because it should have a higher increase in earnings from short-term interest rates going high and staying there. That said, LPL is not as diversified of a company as Charles Schwab, so for more risk-averse investors or people who want to invest in mainly large caps, Charles Schwab would potentially be more appropriate. But if interest rates start falling in the back half of 2023 or early 2024, then LPL would probably have a more significant earnings decline than, let’s say, Charles Schwab that could benefit even if short-term interest rates fall, because that portion of its portfolio tied to long-term interest rates will keep on repricing as long as long-term interest rates maybe stay at 3%, 3.5%, or higher instead of falling back down to, say, 2%.

Lallos: Higher interest rates are positive for many companies in the financials sector—but will this trend persist?

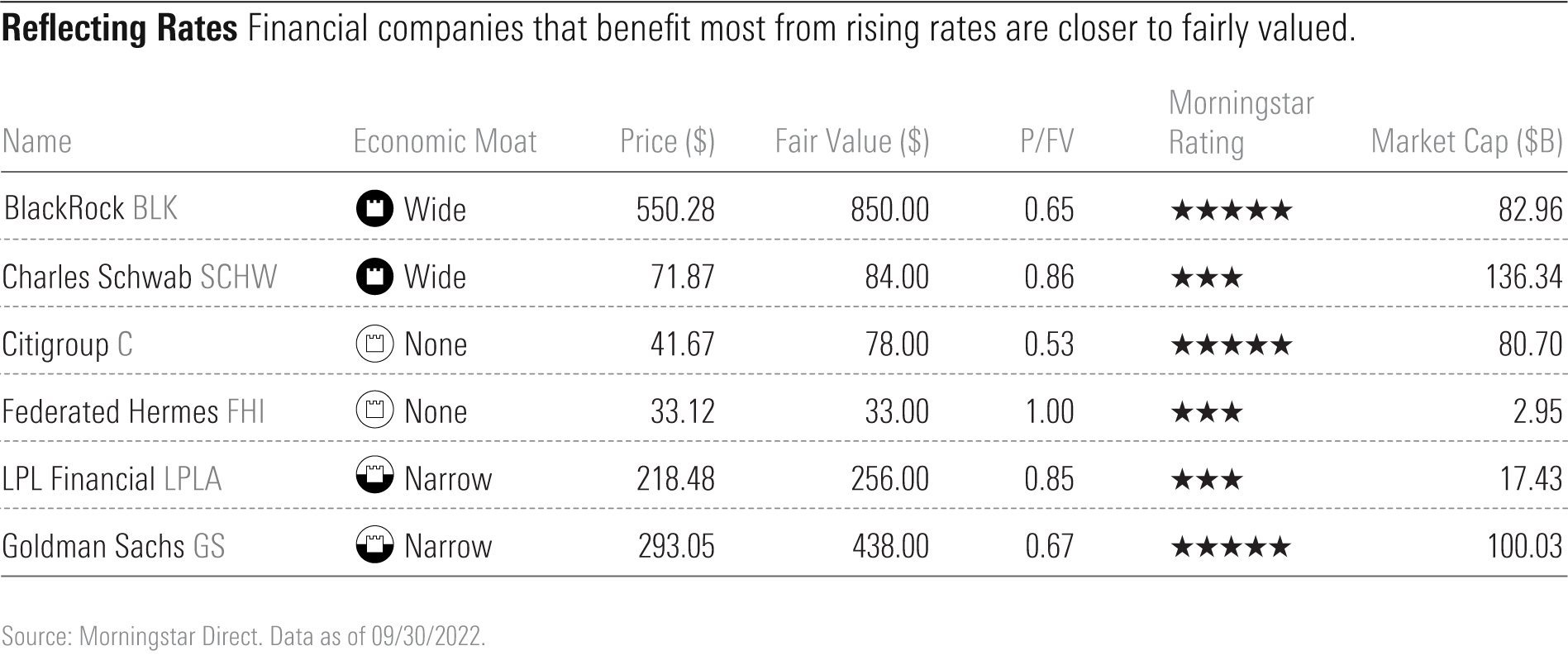

Wong: The more rapid increase and higher expected level of medium-term interest rates have increased the probability that the U.S. will enter a recession. We had already expected that earnings for many financials companies would normalize lower over the next couple of years, as 2021 earnings were elevated from strong mortgage refinancing, investment banking, and trading revenue along with negative loan-loss provisioning. While we project earnings will face some near-term pressure, we believe much of this is already priced into financials sector stocks and that many are undervalued on a long-term basis.

Lallos: Any other picks worth mentioning?

Wong: BlackRock has traded off harder than other asset managers this year, but there’s no fundamental reason for this. The company is at its core a passive investor. Through its iShares exchange-traded fund platform and institutional index fund offerings, the wide-moat firm sources two thirds of its managed assets (and half its annual revenue) from passive products. In an environment where investors are seeking out passive products, as well as asset managers that have greater scale, established brands, solid long-term performance, and reasonable fees, BlackRock is well positioned.

As of the end of September, Citigroup is the most undervalued traditional U.S. bank under our coverage. It’s trading below tangible book value. Citigroup is not one of the most rate-sensitive names, which we think contributes to its current lack of popularity. But the bank is shedding nonperforming segments and refocusing its operations on core competencies and geographies. We think this and an eventual resolution of consent orders from regulators will serve as future catalysts. While Citigroup faces some headwinds, an eventual recovery in card balances will help drive revenue growth.

This article was first published in the Q4 2022 issue of Morningstar magazine.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/6bbc8215-6473-41db-85a9-2342b3761e74.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/YQGRDUDPP5HGHPGKP7VCZ7EQ4E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/5WSHPTEQ6BADZPVPXVVDYIKL5M.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZM7IGM4RQNFBVBVUJJ55EKHZOU.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/6bbc8215-6473-41db-85a9-2342b3761e74.jpg)