Covered-Call Stock Funds Like JEPI Are Popular. Should They Be?

High distributions from these funds don’t tell the whole story.

The People’s Choice

It’s no secret that actively managed stock funds are on the outs. Counting both mutual funds and exchange-traded funds, they suffered $43 billion in net outflows in December 2022, $34 billion the previous month, and $31 billion the month before that. After a while, as the saying goes, such losses can become real money.

Covered-call funds, however, have attracted $65 billion in net inflows over the past three years. Through every month of that period, their net sales have been positive. (For further information on the interest in such funds, see “Why Investors are Pouring Billions into Covered-Call ETFs,” by Katherine Lynch.)

The reason for their appeal is obvious: they make high ongoing distributions. The largest such fund, JPMorgan Equity Premium Income ETF JEPI, boasts an official SEC yield of 7.04%. Similarly, BlackRock High Equity Income BMCIX registers 6.65%, and Invesco Income Advantage U.S. SCIUX pays 5.77%. Income far surpassing that of Treasuries, coupled with the stock market’s capital-gain potential? Sign me up!

A Complex Investment

Regrettably, the matter is not that simple. The difficulty begins with their names. I have thus far described these as “covered-call” funds because that is their most common designation. However, as most covered-call funds are not so labeled—and several do not even invest in that fashion—that term is flawed. Therefore, I will now adopt Morningstar’s phrasing and call them “derivative-income” funds.

Historically, as implied by the “covered-call” description, derivative-income funds have invested in an equity portfolio, then sold call options on those positions. Doing so generated cash for shareholders. Of course, those transactions did not acquire something for nothing. The trades gave as well as received. If equities were to rally, the funds would concede potential capital appreciation, as the owners of those call options could purchase their stocks at below-market prices.

These days, rather than trade options directly, some derivative-income funds achieve the same result indirectly, by owning “equity-linked notes,” or ELNs. In effect, these notes deliver the combined performance of two distinct investments: 1) the underlying stock and 2) the sale of its call option.

The Yield Problem

This divergence mucks up the fund’s reported yields. Although the investment techniques of 1) selling covered calls and 2) buying ELNs perform similarly—the marketplace is too efficient for them to greatly diverge—they are taxed differently. By IRS regulations, the proceeds from selling options are classified as capital gains (usually short-term), while ELN returns are nonqualified income.

Thus, the SEC yield calculations for derivative-income funds are misleading. The three previously referenced funds have high official yields because they hold ELNs. In contrast, rival offerings that sell call options rather than purchase ELNs have paltry SEC yields because their payments consist mostly of capital gains, which are omitted from those computations. For example, Global X S&P 500 Covered Call ETF XYLD has an SEC yield of 0.95%, while First Trust BuyWrite Income ETF FTHI registers 1.14%.

Conflicting names, conflicting tactics, conflicting yields. What is an investor to do?

The Correct Yardstick: Total Returns

The answer to that question is easy: Ignore the funds’ payouts. I realize that sounds silly, as distributions, either in the form of income or capital gains, are why derivative-income funds exist. But those payments are deceptive because they represent the benefit from the derivative trade but not its cost. Effectively, derivative-income funds swap tomorrow for today. Perhaps those exchanges will prove worthwhile. One cannot know, however, by assessing only half the deal.

Happily, the statistic of total return measures the entire package. It accounts not only for the moneys that derivative-income funds receive for surrendering potential capital growth but also for the extent to which that growth is forfeited. If the latter exceeds the former, derivative-income funds are merely a parlor trick. Investors who seek upfront cash would be better off purchasing a conventional fund and then periodically selling its shares. In that fashion, they could duplicate the derivative-income funds’ ongoing payouts while achieving a higher future return.

The logical rivals to derivative-income funds are either dividend-stock funds or … this once again is confusing … equity-income funds. Wait, you say, you have already mentioned two derivative-income funds that have “equity income” right in the name. How can such funds be rivals to themselves? The answer: There are two flavors of equity-income funds. The traditional variety invests in stocks without using derivatives. However, some newer “equity-income” funds do incorporate such investments and thus land in the derivative-income category.

Behind the Curve

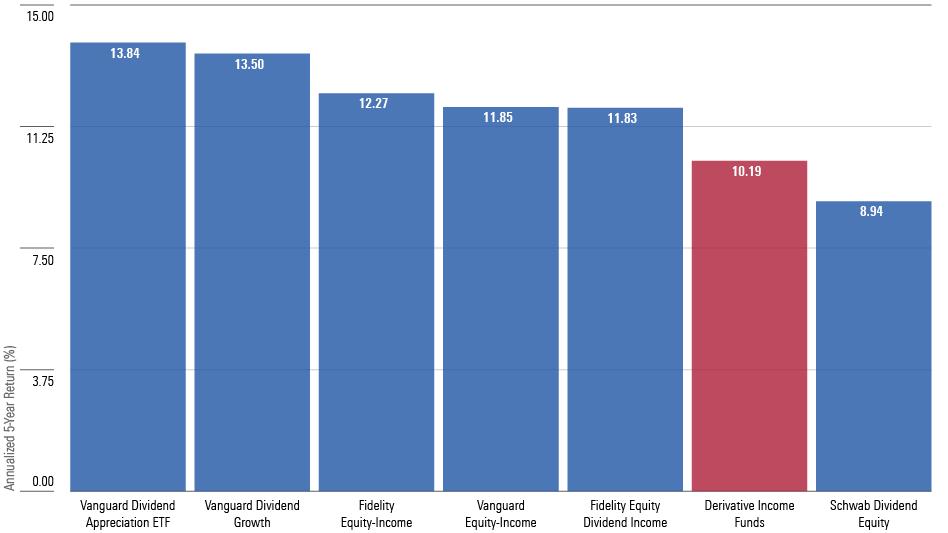

Sigh. These funds are so messy! Nevertheless, let’s see the results. The following chart shows the average five-year total returns for all derivative-income funds that hold large-blend U.S. stocks (few have 10-year records), compared with those for each of the 1) dividend-stock and 2) traditional equity-income funds managed by the three largest discount brokers, Vanguard, Fidelity, and Charles Schwab SCHW.

Total Returns

Count me unimpressed. I’m not sure what went on with Schwab Dividend Equity SWDSX, but Vanguard’s and Fidelity’s pedestrian competitors thumped most derivative-income funds. (In fact, Vanguard’s dividend funds outgained all of them.) The natural counterargument is that derivative-income funds are safer than stock market indexes. Fair enough, but so too are dividend-stock or old-school equity funds. Consequently, the risk-adjusted outcomes for derivative-income funds are similarly disappointing.

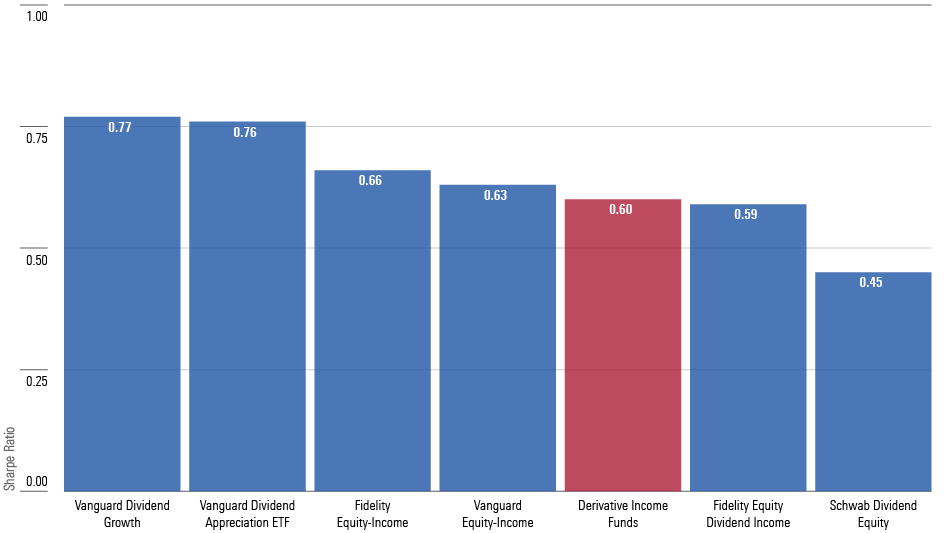

Risk-Adjusted Total Returns

Conclusion

Supporters of derivative-income funds can offer two additional defenses. One, the category’s largest fund, JEPI, has recorded a higher Sharpe ratio since its May 2020 inception than the above rivals. True, but as that outperformance occurred solely during the fund’s first 18 months, with nearly all the fund’s assets arriving afterward, the achievement was largely theoretical.

The other rebuttal is that derivative-income funds perform best in choppy markets rather than ones boasting a double-digit annualized gain. Hmmm. Much can be said about that claim, which concerns not only derivative-income funds but also other high-distributing strategies. More about that topic on Friday.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ECVXZPYGAJEWHOXQMUK6RKDJOM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/KOTZFI3SBBGOVJJVPI7NWAPW4E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/V33GR4AWKNF5XACS3HZ356QWCM.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)