Skipping Your Morning Coffee Won’t Make You a Millionaire

As fables go, however, this one is relatively useful.

Storytellers

“Nobody remembers formulas,” says economist Richard Thaler. “But they remember stories.” The great communicators know that. When attacking government programs, Ronald Reagan skipped statistics. Rather, the future president disparaged Chicago’s “welfare queen” (who did, in fact, exist).

The same applies to personal-finance coaches. No pie charts for them; they tell stories. Among their favorites is the $1 million cup of coffee. If all those dollars squandered at the coffeehouse were invested in the stock market, consumers would have another $1 million when they retired. Suze Orman’s admonition is the best known, but variations on the theme do abound.

Is this correct? If so, what lessons should investors draw from this exercise?

The short answer to the initial question is that the strategy might technically achieve the goal, but it cannot do so materially. That is, under some assumptions, investing money that would otherwise have been spent on morning coffees could create a $1 million portfolio—but only in nominal terms. When adjusted for inflation, the result almost certainly will land well short of the mark.

The Coffee Fund

Let’s run through the computation. From ages 25 to 64, our subject wishes to order one coffee drink each morning, whether working or not. However, he declines the indulgence, investing instead in an equity fund. Over that 40-year period, that fund earns a real annualized gain of 6%. Yearly inflation is 3%.

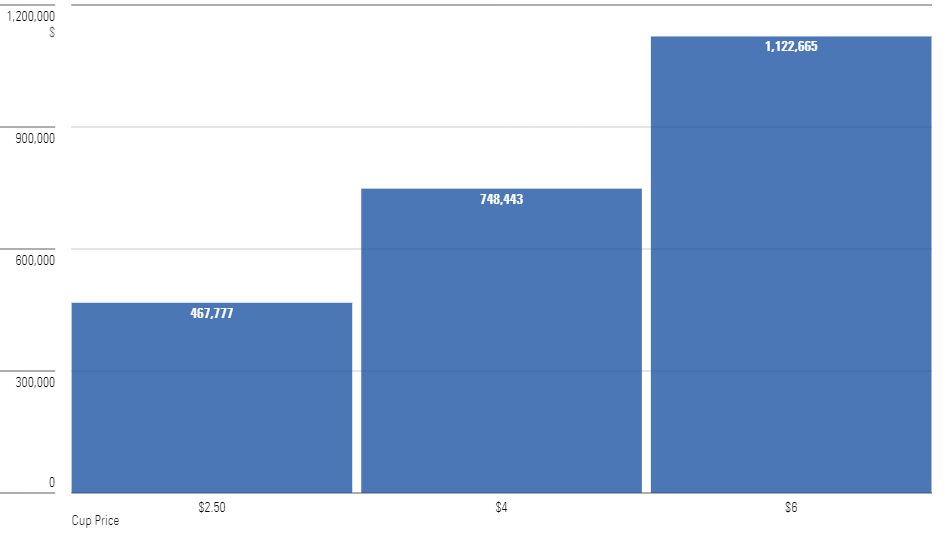

We will assess three potential cup prices: 1) $2.50 for coffee only, 2) $4 for a cappuccino, and 3) $6 for a drink mixed with whipped cream and enough sugar to satiate a bear. (Orman cites $7 for her coffee example, but even in New York City, where I now live, that figure is a stretch.) When calculating the nominal value of the coffee fund, I increase the cost of the cup each year by the rate of inflation. Meanwhile, the annual gain on the portfolio is 9.18%—the product of the real equity return and the inflation rate.

Under those conditions, the most extravagant consumer will accumulate $1.1 million in nominal moneys by age 65. The midrange customer will possess three fourths of a million dollars, and the no-frills buyer slightly below $500,000.

The Coffee Fund: Future Dollars

So yes, that $1 million forecast can be achieved. Admittedly, reaching that mark requires the somewhat bold assumption that the investor purchase the most expensive coffee drink, 365 days per year, while not buying ingredients to make the concoction at home. The exercise involves abandoning coffee drinks, not substituting for them. But I cannot in good conscience dispute the claim.

Getting Real

This, however, is insufficient. The whole idea of investing in equities is to own securities that grow with inflation, which conventional bonds do not. (Motivational speaker Nick Murray would illustrate the concept of purchasing power by holding up a 3-cent stamp and asking listeners the current price of mailing a letter. That ploy would fail today because few people buy stamps.) Therefore, one cannot reasonably pretend that inflation does not exist when evaluating the outcomes.

And most assuredly, $1 million to be received in 2064 will not fill today’s shopping cart. On the bright side, it will buy more technology, although not necessarily more communications. (My cellphone bill is much higher than when I rotary-dialed on evenings and weekends to receive long-distance discounts.) However, real estate will be far costlier, as will food, energy, and other everyday goods.

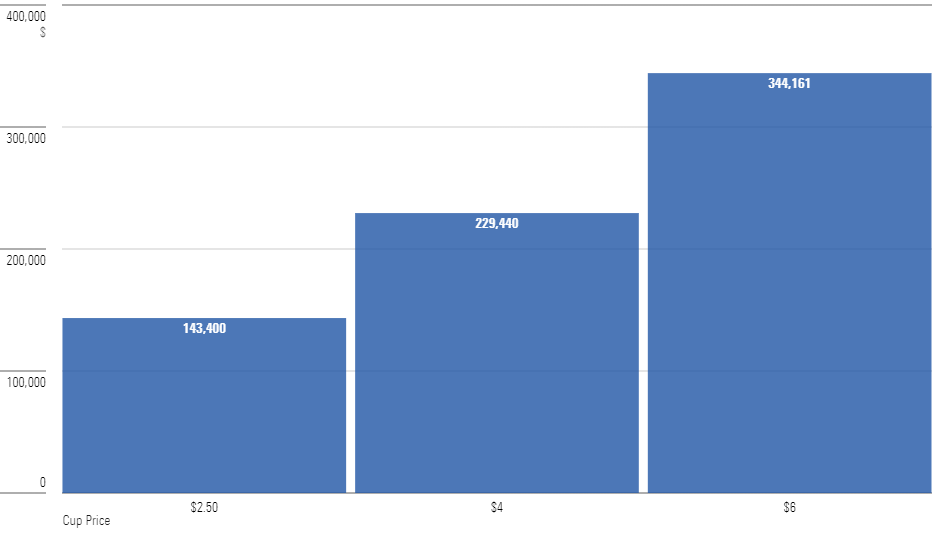

This is how the coffee funds would look when restated in 2024 dollars:

The Coffee Fund: Today's Dollars

If we translate those assets into a 4% annual real withdrawal rate, thereby representing their spending power, those amounts become, roughly speaking, 1) $5,700, 2) $9,200, and 3) $13,800 per year. Although not insignificant, those figures are nowhere near the $40,000 that could be spent from a $1 million portfolio, per that same withdrawal-rate math.

The Verdict

Overall, I have mixed emotions about the coffee kvetch. To start, the parable is misplaced. As evidenced by the demographics of Starbucks’ SBUX customers, shoppers who buy expensive coffees can usually afford to do so. No doubt, they would be happy with additional retirement earnings. But the coffee fund is unlikely to make or break their finances. The coffee example does not speak to those who most need the advice. (Then again, they are not the narrative’s intended audience, which consists instead of potential financial-advisory clients.)

Also, at least to my taste, there are easier ways of conserving money than forswearing 14,610 treats. (Not to mention the social encounters that often accompany such purchases.) For one, live somewhere slightly cheaper. The $6 cup amounts to $180 in extra monthly rent, while the $2.50 drink makes for a difference of only $75. For another, buy a late-model used sedan rather than a new SUV. Investing the savings both from the upfront costs and from the ongoing gasoline bills will fatten retirement portfolios more than skipping morning coffees.

Such quarrels aside, I do support the homily’s underlying message, which is that, for most Americans, underinvesting is a choice. For the working poor, it is not. Having been raised under such conditions, I understand that some families are the exception to the general rule. There comes a point where neither blood nor retirement savings can be squeezed from the wage turnip. Among the middle and upper classes, though, those extra dollars can usually be found.

If so, the tale of the coffee cups should provide some comfort. No, setting aside $4 daily will not lead to a $1 million retirement portfolio in real terms, unless the investor obtains bitcoin at $500 or Nvidia NVDA at $5 (which was possible in 2015). Per this column’s calculations, though, $18 per day would accomplish the task. That equates to a 7.8% savings rate for a worker with an $80,000 annual salary. Should that employee have access to a 401(k) plan that offers a company match, his personal contributions might well be lower yet. Such a plan seems achievable.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/YBH7V3XCWJ3PA4VSXNZPYW2BTY.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-24-2024/t_a8760b3ac02f4548998bbc4870d54393_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)