Pension vs. 401(k): Which Retirement Option Wins in an Inflationary Environment?

Measuring the effect of inflation on fixed incomes.

The Pension Problem

A friend of the family sought my advice. When starting his first real job, he faced an unusual (although not unique) decision. He could join his company’s pension plan, or he could establish a 401(k) account. Which option should he select?

After reviewing the materials, I concluded that few employees presented with such a dilemma have ever made a truly informed choice. Making the selection requires evaluating several moving parts, such as the details of the pension’s benefits, the vagaries of the investment markets, and the length of the worker’s tenure (which, of course, remains entirely to be determined). The task is complex.

Indeed, I have not yet resolved it. However, my preliminary inquiry has sparked today’s topic: the effect of inflation on fixed incomes. As with most pensions, the benefits from my friend’s organization are paid in nominal dollars. That drawback distinguishes them from Social Security checks, which, as demonstrated by this year’s fat 8.7% increase, are fully adjusted for inflation. The latter, of course, is more valuable. But how much more?

(Note: Although I have framed this article as comparing Social Security receipts against those from fixed-rate pensions, I could instead have contrasted the payments made by Social Security with coupons from bonds. Whatever the form, retirees frequently receive income from both real and nominal sources.)

A Case Study

Assume two freshly minted retirees, each age 65, each with a 30-year time horizon. (So far, so conventional.) One will receive $4,167 per month from the Social Security Administration for a total of $50,000 each year. The other somehow missed out on Social Security but receives either—depending upon your interpretation—$50,000 annually from a pension or $50,000 in bond coupons.

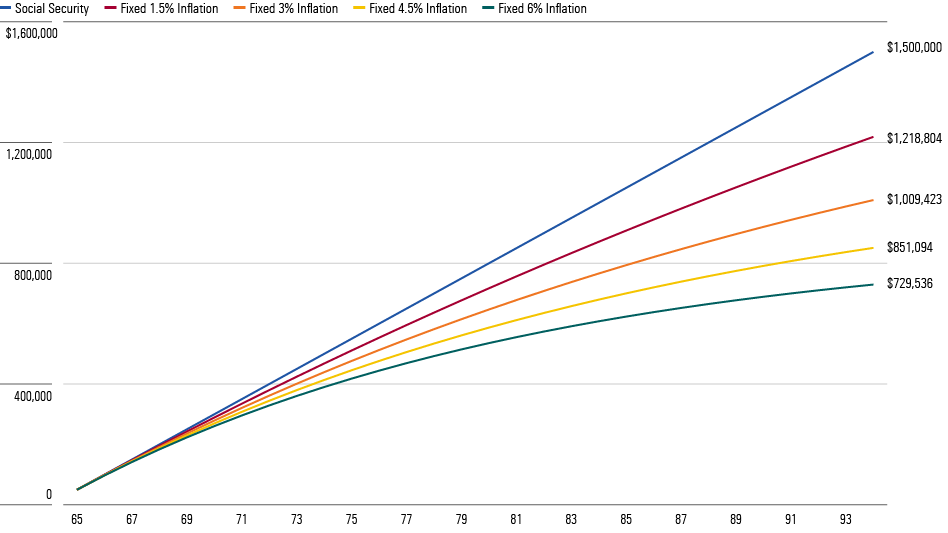

The chart below shows the real value of the next 30 years’ worth of payments for each retiree, assuming four annualized inflation rates: 1.5%, 3%, 4.5%, and 6%.

Real Cumulative Payouts

The first retiree requires only a single line because no matter how inflation behaves, the Social Security benefit remains unchanged in real terms. It supplies $50,000 each year, for a total of $1.5 million. If inflation is very mild, at 1.5%, the second retiree pockets a real $1.22 million, suffering an 18% haircut. The deficit widens to 33% if inflation is 3%, grows to 43% if inflation averages an unpleasant 4.5%, and balloons to 51% if it becomes a downright depressing 6%.

The Final Years

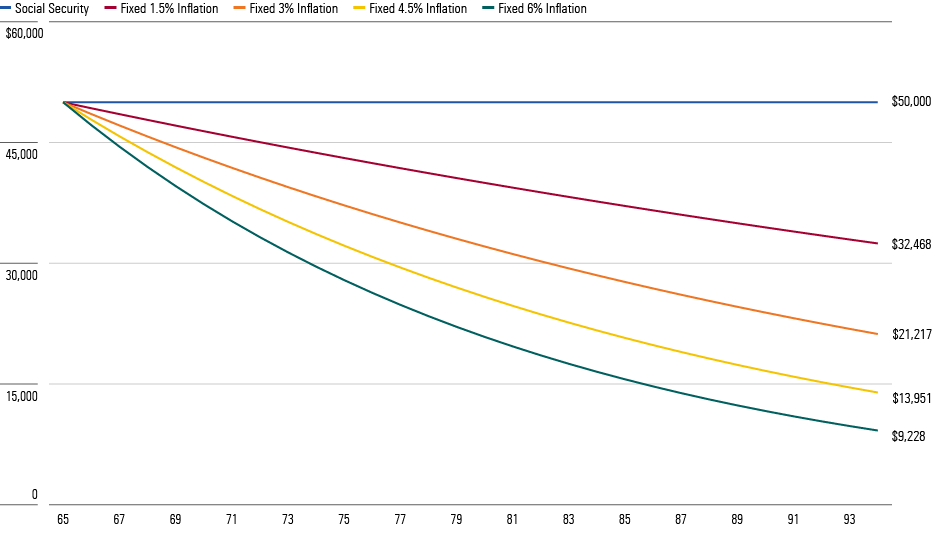

That perspective, arguably, minimizes the damage wrought by inflation, because the cumulative results disguise the critical issue: what happens during the later stage of retirement. If the second retiree habitually spends what she receives, the fact that inflation initially has only a modest effect does her no good when she reaches her 90s. She requires fresh proceeds. And, as the following illustration shows, those moneys are sorely lacking.

Real Annual Payouts

Oh, dear. Even with the highly favorable—and unlikely—inflation forecast of an annualized 1.5%, when year 30 arrives the second retiree’s after-inflation income has dwindled to slightly under $32,500. The news worsens from there. With moderate inflation of 3%, the final payout (at least for this exercise; with luck, our retiree will yet live longer) barely exceeds $21,000. With 6% inflation, she barely receives anything at all. Such are the perils of fixed incomes.

Deferred Retirements

This example addressed the immediate case: when the payments directly follow the retirement date. However, as I realized when working through the pension puzzle, there is also the indirect case, triggered if my family’s friend were to leave his company before retiring but after becoming invested in the pension plan. Should that occur, his pension benefit would be determined when he exited the firm but paid in the future. In effect, he would receive a deferred annuity.

With some effort—all right, a great deal of effort, as the enrollment documents are obscure—I determined that this benefit would also be nominal. That is, just as the payments received after the retirement date are not adjusted for inflation, neither would the calculated deferred benefit float with inflation, between the time of the employee’s departure and the date of his retirement.

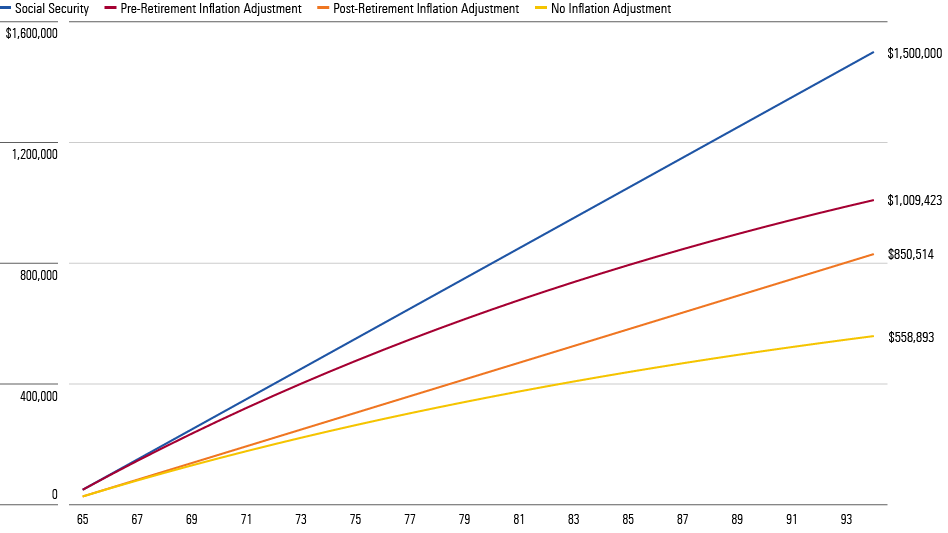

As we have seen, forgoing inflation adjustments substantially reduces the value of pension benefits. This article’s fourth and final exhibit makes that abundantly clear. It considers an employee who earns the same $50,000 annual pension but at age 45. After leaving the company, the employee works for another 20 years, then retires at 65. This time, though, the pension payments have been deferred.

I computed the value of the pension under four circumstances, each assuming a 3% inflation rate. The first treats the pension benefit as if it were Social Security, suspended for 20 years but adjusting for inflation while the employee continues to work. It is then delivered on an inflation-adjusted basis from ages 65 through 94. The second assumes the benefit is inflation-adjusted from age 45 until 65, then fixed during retirement. The third takes the opposite approach. The fourth models the pension plan’s actual approach by providing no inflation adjustment.

Real Cumulative Payouts: Deferred Case

The chart imparts two key points. First, when receiving inflation adjustments, better now than later. Floating the benefit while the employee was still working and then fixing it during retirement created a cumulative real value that was almost $180,000 higher than doing the reverse. That held even though the retirement period was 30 years, and the deferred working period only 20.

Second, when evaluated under its true conditions, that putative $50,000 annual benefit shed almost two thirds of its value. Bad news for the employees, but good news for those worried about companies (and government bodies) being too generous with their pension promises.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WNDFS2S4FNA6LEJDB2Y6E4XHYQ.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/YBH7V3XCWJ3PA4VSXNZPYW2BTY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EC7LK4HAG4BRKAYRRDWZ2NF3TY.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)