Could Private Equity Work in Workplace Plans?

Our research on private equity in large pension plans shows mixed results.

When it comes to retirement account investments, private equity has long been included in pension plans. But as pension plans play a smaller and smaller role in the retirement landscape, the debate has grown around private equity’s role in defined-contribution plans like 401(k)s.

On one hand, private equity could potentially offer higher returns and uncorrelated asset exposure, theoretically improving retirement outcomes. On the other hand, private equity is generally accepted to be a riskier asset and is not as liquid as investments most often found on 401(k) lineups—which could expose workers to significant losses.

To evaluate how these hands balance, my colleague Jasmin Sethi and I analyzed the usage of private equity in 20 of the largest private pension plans over the span of 12 years in our recent paper. While we also lay out the regulatory landscape for private equity in retirement accounts and review the prior literature on this topic in the paper, I’ll focus on our unique data analysis and a couple of key findings here.

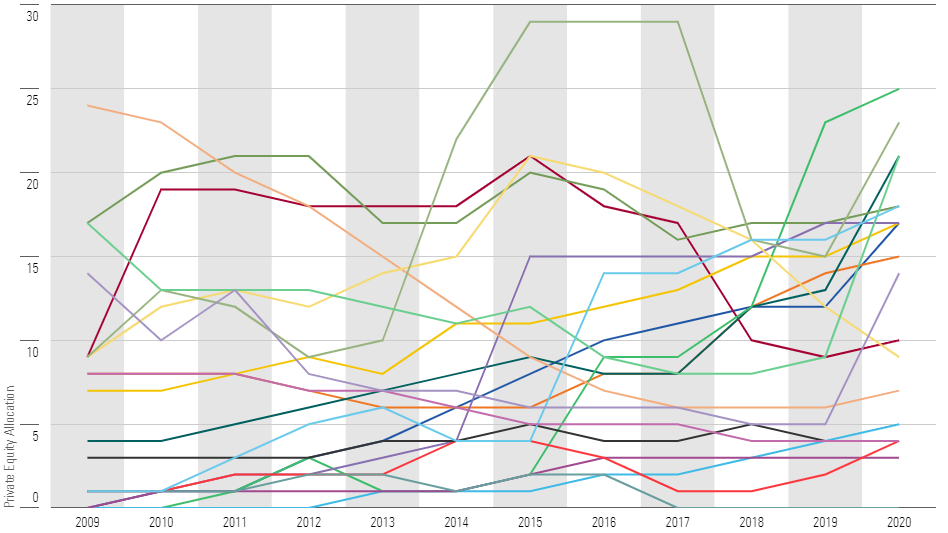

No Discernible Pattern to Private Equity Allocation Decisions by Plans

Before examining the data, our supposition was that we would see consistent trends in the percentage of the portfolio that plans were allocating to private equity, either across time, within plans, or both. We found almost none of the above.

For brevity, I’ve condensed what is presented in four charts in the paper into one chart below, tracking the private equity allocation percentage across all 20 plans over 12 years. In the paper, we present the plans grouped by their quartile based on plan assets under management, as one thought was that plans of a similar size would allocate similar portions of their portfolios to private equity. As the paper discusses, that was not the case.

Allocation to Private Equity by Year—Largest Plans

The condensed chart in some ways better illustrates how noisy the data is. The only trend to be found is that most plans increased their allocation to private equity over this 12-year span, but the timing and degree of those increases vary widely.

Plans Were Average, Not Better Nor Worse, at Identifying the Best-Performing Private Equity Fund Families

One unique element of our analysis was our ability to pair the data we collected on pension plans with the data and insights PitchBook has on private equity funds. For all the plans we looked at, we identified the private equity funds in their portfolios and were able to pull in the corresponding characteristics, returns, and analytics for those investments from PitchBook. In the paper, we dive into the return profiles of the selected investments as well as examine which funds and managers were most popular among the pension plans.

While returns are a common starting place for analyzing performance, there are particular challenges with private equity funds when it comes to comparing just returns, two of which are worth noting here.

The first is not unique to private equity funds, but rather an important reminder that when comparing performance it should always be in a peer group to account for varying risk profiles. Similar to how a muni fund and a small-cap equity fund are on unequal footing when just returns are examined, private equity funds span several categories or classes.

The second challenge with private equity returns, which is unique to private markets, is that these funds are more akin to closed-end funds than open-end funds. That is to say, there is a limited window during which the fund gathers investors and capital, and after this window, new investors are generally unable to join. When this fundraising period is closed and the fund begins investing is referred to as the “vintage year” of the fund. Comparing the raw performance of funds from different vintage years would be like comparing the returns for the first five years of two mutual funds, except one launched in 1998 and one launched in 2010. Those are two very different markets and environments to have as backdrops for mutual fund performance.

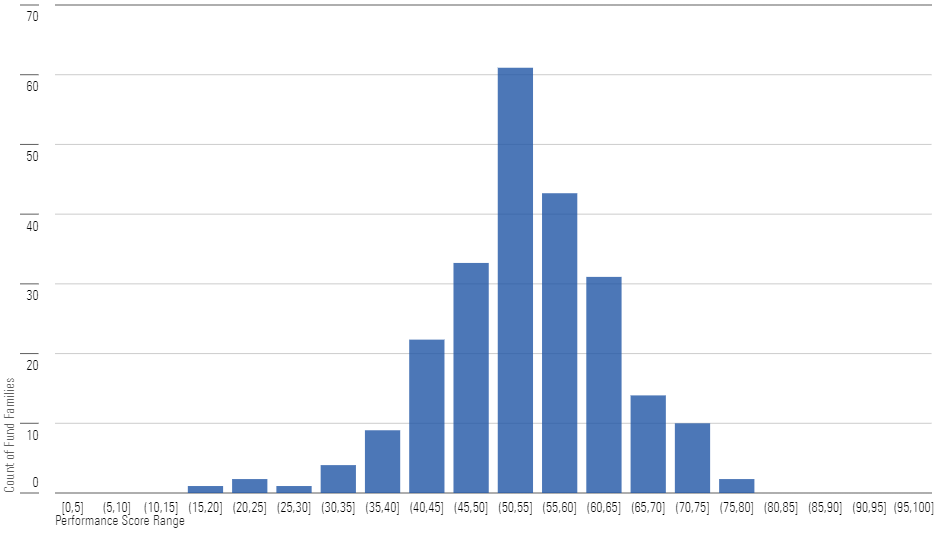

Given these challenges in comparing just returns, PitchBook has developed a quantitative framework for assessing the track record of private-market managers called the PitchBook Manager Performance Score. This score allows for more accurate comparisons between managers as it accounts for variation in vintage years and benchmarks performance against a reasonable peer group. The score ranges from a low value of 0 to a high of 100, and fund families—that is funds from a manager following the same strategy, potentially across multiple vintage years and unique funds—are distributed across the spectrum in roughly a bell curve, with a center around 50.

The chart below almost looks like that bell curve I just described. However, it only has the fund families found in the 20 pension plans we looked at rather than the whole universe of fund families. The distribution does not span the full range of scores, but it has a similar clustering around the middle, with more than 72% of the fund families scoring between 45 and 65.

Distribution of Performance Scores of Pension Plan Selected Private Equity Fund Families

The fact that the distribution of fund families invested in by the pension plans mirrors the overall market is not terrible, but it’s also not fantastic. The pension plans are not clustering below the mean with poor performers. However, they are also not consistently selecting the best strategies. While this is not a particularly surprising finding, it does not bode well when contemplating how private equity could show up in defined-contribution plans like 401(k)s.

No Consistent Approach Emerges for Defined-Contribution Plans to Mimic

Our findings throughout the paper were both expected and surprising.

High variability is a known feature of private markets, but the fact that large pensions were largely unable to concentrate their investments in high performers was notable. The addition of high variation in how much pensions were allocating to private equity was unforeseen. While there are potential return and diversification benefits to including private equity in a retirement portfolio, these pension plans do not provide a consensus approach that can be broadly applied to defined-contribution plans.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/f3c31470-cc00-45ac-b20f-d2928ec12660.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/YBH7V3XCWJ3PA4VSXNZPYW2BTY.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-24-2024/t_a8760b3ac02f4548998bbc4870d54393_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/f3c31470-cc00-45ac-b20f-d2928ec12660.jpg)