401(k)s for Higher-Income Employees

As their needs are greater, so must be their contribution rates.

A Different Situation

Tuesday’s column, “What is the Right 401(k) Contribution Rate?,” addressed retirement planning for employees with median salaries. It showed that workers who receive typical wages should be able to achieve acceptable retirement incomes by combining their Social Security benefits with their 401(k) assets. As a general rule, a 7% annual 401(k) contribution rate (counting company matches) throughout such participants’ working years should generate a 70% income-replacement rate, while a 9.5% contribution rate would make for 80%.

(These estimates are less precise than they sound, owing to the vagaries of investment performance. Barring either extraordinary good or bad market returns, however, the figures will prove reasonably close to the mark.)

Today’s article concerns higher-income employees: those with salaries approaching $160,000, which currently delineates the 90th percentile of wage earners. Their 401(k) math differs because Social Security payments will not replace less of their salaries than they do for median-income employees. On average, Social Security supplies about 40% of preretirement wages for workers with average wages, as opposed to 30% for their higher-income counterparts.

(Such projections assume that the Social Security program will persist in something approaching its current form. While I think that is a fair bet, skeptics may wish to save above and beyond this article’s recommendations.)

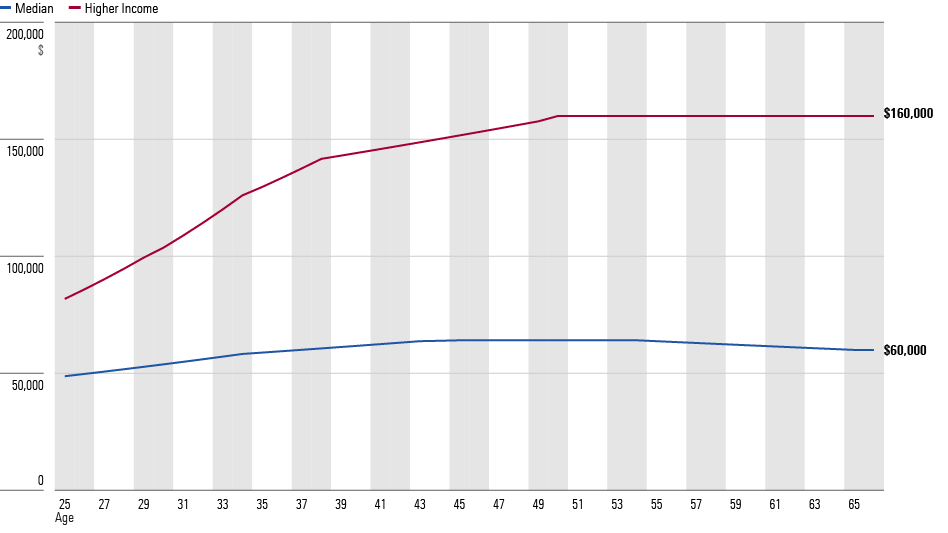

Two Salary Curves

The proportion provided by Social Security shrinks because higher-income employees take longer to hit their salary peaks. (The amount of income replacement from Social Security declines further for those who exceed the Social Security Administration’s tax limit of $160,200, but that is another matter.) While median-income workers earn roughly similar wages throughout their careers, higher-income employees take 25 years to reach their salary maximum. Those lower-paying years factor into the Social Security formula, reducing the benefits.

The chart below, based on this secondary source—I prefer using primary sources, but in this case, the data is difficult to obtain—shows the difference in salary progressions. Higher-income employees not only make more money (obviously), but their salaries also increase more aggressively with time.

Salary Progressions: Median- and Higher-Income Employees

The salary-curve difference also affects 401(k) accumulation. Because median-income workers receive relatively strong wages when they are young—85% of their salary maximum by age 30 versus 65% for higher-income employees—they get greater bang for their buck when using the same contribution rate. Measured as a percentage of their peak earnings, median-income workers put more money to work early on, thereby easing the burden on their lifetime contribution rate.

In short, higher-wage employees must save more to achieve the same income-replacement coverage from their 401(k) accounts.

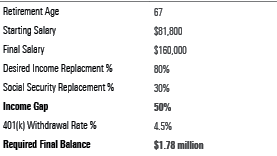

The Test Case

Let’s consider an example. As with Tuesday’s article, I assume that the employee will work until age 67. At that time, they will: 1) file for Social Security, receiving 100% of the official full benefit, and 2) begin withdrawing from the 401(k) plan at an inflation-adjusted rate of 4.5% per year. That withdrawal percentage exceeds the figure that is usually recommended, but the time horizon is shorter than the customary 30 years, as I have stipulated a later retirement date. Also, my analysis considers a single investor rather than a couple with a joint life span.

With those assumptions, our hypothetical higher-income employee will need to have accumulated $1.78 million of 401(k) assets upon the retirement date to achieve an 80% income-replacement ratio. (All dollars, in this paragraph and elsewhere, are presented in 2023 values.)

Higher-Income Employee Assumptions

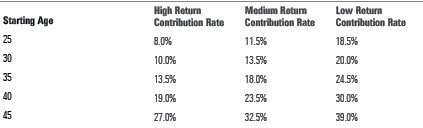

Required Contribution Rates

I then computed the necessary lifetime 401(k) contribution rates to generate that final balance while varying two conditions: 1) the starting age for 401(k) participation and 2) the portfolio’s performance. The latter considers three investment scenarios: 1) High Return, which uses historic asset-class results; 2) Medium Return, which shaves the projected real annualized equity return to 5% from 7.5%; and 3) Low Return, which cuts the stock forecast further, to 2.5%.

The portfolios’ asset allocations mimic how target-date funds invest. (For further details on the investment assumptions, see Tuesday’s article.)

Below are the results.

Required Contribution Rates

The good news for higher-income employees is that if they start their 401(k) accounts early and receive moderate or better investment performance, they should be able to reach the 80% retirement income standard. For participants with incomes from $100,000 to $150,000, Vanguard reports, the aggregate current contribution rate of its customers is 12.2%. That is sufficient.

The bad news for higher-income employees is that the projections give them little wiggle room. Reaching the income-replacement target when equity performance is sluggish calls for either an initial 18.5% 401(k) contribution rate or a 20%-plus savings rate later in the employee’s career. The first possibility is unrealistic, the second severe. Nor can higher-income employees tolerate investment delay: Those who wait until 35 years old to begin contributing to their 401(k) plans in earnest are implicitly depending upon a bull stock market to bail them out.

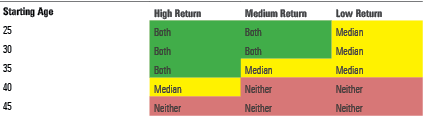

A Stricter Standard

This article’s final table compares the retirement outcomes for higher-income employees versus those of their median-income peers, assuming a 15% contribution rate and the same matrix of starting ages and investment returns. Green boxes show that both sets of employees achieved the 80% income-replacement goal. Yellow boxes indicate that only the median investor managed the feat, while pink boxes signify that neither was successful.

Goal Achievement, With 15% Contribution Rate

With 401(k) investing, one contribution rate size does not fit all. Higher-income employees must do more.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/YBH7V3XCWJ3PA4VSXNZPYW2BTY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EC7LK4HAG4BRKAYRRDWZ2NF3TY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WNDFS2S4FNA6LEJDB2Y6E4XHYQ.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)