How Short-Term Bond Funds Went Wrong (Again)

Echoes of the financial crisis reverberated across short-term and ultrashort bond funds in March 2020.

Back in 2008, several funds in the short-term bond and ultrashort bond Morningstar Categories that had invested in securitized bonds backed by subprime mortgage loans got caught in a liquidity trap, as falling prices led to heavy redemptions and forced selling. The destruction of value was severe enough to put some funds, such as ultrashort bond heavyweight Schwab YieldPlus, out of business. It was a devastating outcome for investors who believed these vehicles were just a little bit riskier than cash.

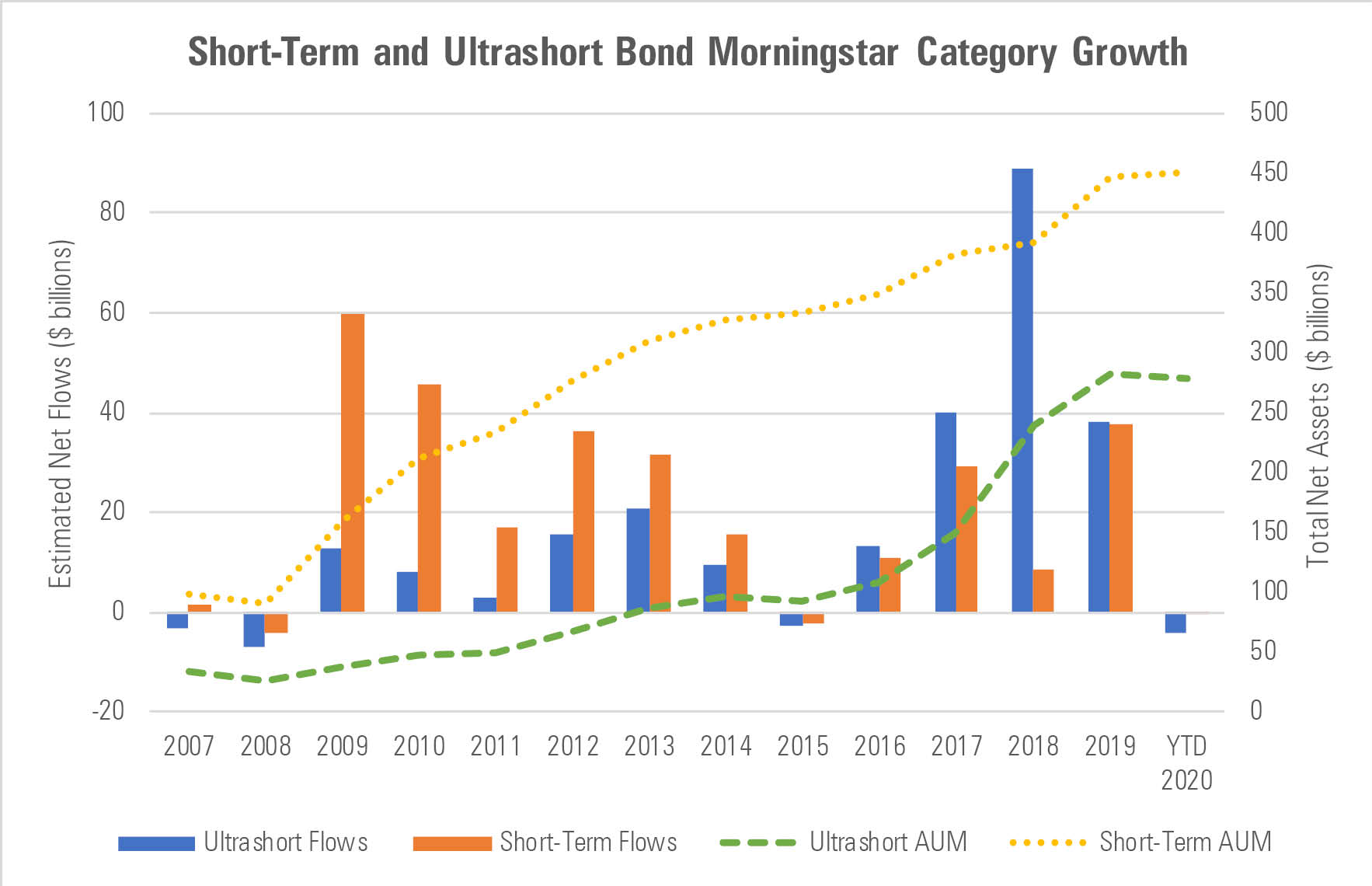

After the financial crisis, short-term bond funds started to look a lot more compelling because of the Federal Reserve's prolonged zero interest-rate policy and fears that all-time low yields increased the perception that a painful bear market for bonds was just around the corner. While the memory of high-profile blowups may have deterred some investors from ultrashort bond funds initially, many came around once the Fed's rate hikes (beginning in December 2015) made these funds' yields more enticing. Relatively safe money market funds, meanwhile, were increasingly restricted from taking advantage of some of the higher-yielding issues available to ultrashort bond funds.

All told, the short-term bond category has more than quadrupled in size since 2007, while assets in the ultrashort bond category increased almost tenfold. In fact, half the ultrashort bond funds in the category today were launched after 2013, including quite a few actively managed exchange-traded funds.

Source: Morningstar Direct.

Too Close to the Sun? For much of the decade following the financial crisis, these fund categories delivered meager but steady positive returns in the low single digits (sometimes a little less). Those that took on more risk and paid out modestly more yield in the process generally outperformed, but not by much. That extra helping of risk came back to bite many short-term and ultrashort bond funds in March 2020, though, when the market's panic over the global spread of the coronavirus sent bond prices crashing. The speed at which liquidity evaporated and bond prices dropped surprised even the most seasoned managers, and the worst-impacted short-term and ultrashort bond funds suffered losses ranging from the high single digits up to 20% from Feb. 20, 2020, through March 23, 2020. Investors were clearly spooked: They withdrew a record-breaking $23 billion and $29 billion (on a net basis) from the short-term and ultrashort bond categories, respectively, in March.

The picture looks much improved just a few months later, but investors have government policymakers to thank for that. Their seemingly giant efforts during the 2008 crisis wound up paling by comparison. The Fed's rapid, massive, and unprecedented response to shore up liquidity in the market this time around sparked a quick turnaround. For 2020 through June 30, only 16 short-term bond funds (10% of the category) and just five ultrashort bond funds were down more than a percent. Investors have gone back to socking money into these funds, too: Each category took in more than $8 billion in May.

By pledging to do everything in its power to keep the bond market functioning, the Fed may have averted a systemic liquidity crisis, but it's too early to know the extent to which weakness in the economy will translate to credit losses for the most aggressive short-term and ultrashort bond funds. Whether these funds next encounter stress in a year or 10 years, the latest sell-off is a reminder that volatile return profiles are a poor match for investors' expectations for safety in these categories. Even if battered bond prices ultimately recover, investors often don't stick around long enough to benefit.

For those who buy a short-term or ultrashort bond fund because they want a low-risk investment, the lessons from the recent market turmoil look a lot like the lessons learned in the financial crisis:

1) Don't chase the highest-yielding funds. Nine out of the 10 worst-performing funds in the short-term bond category during the COVID-19 sell-off, and eight out of the 10 worst ultrashort bond performers, began 2020 out-yielding more than 80% of their competitors (comparing trailing 12-month yields across distinct funds). Income is an important component of returns for funds that invest in short maturities, but don't get greedy. More yield comes with more risk, plain and simple. Picking a fund with a moderate yield can lead to a steadier return profile that reduces the risk of big losses during credit sell-offs.

2) Look for a Treasury buffer. Investors who purely want safety and don't care about income would be well-served by low-cost short-term and ultrashort bond funds that invest entirely in U.S. Treasuries. Make no mistake, short-dated Treasuries offer little in the way of income or return potential given the reinstatement of the Fed's zero interest-rate policy. Nevertheless, it's prudent for short-term and ultrashort strategies to keep some Treasuries on hand--or cash and other liquid U.S. government-backed securities--for diversification and to provide ballast and liquidity when times get tough. When investors panic, Treasuries are often the only assets that stay afloat. Funds that invest solely in credit instruments are more vulnerable to price declines during an economic downturn or periods of acute credit-market pain. To be on the safe side, look for funds that keep, at a minimum, 15% to 20% in some combination of liquid U.S. government-backed debt and cash.

3) Start by focusing on funds with higher-quality profiles … Ratings agencies don't have a perfect record when it comes to gauging credit risk (see the massive wave of downgrades of formerly AAA rated mortgage-backed securities in 2007 and 2009), but we don't see evidence that that they systematically underestimated the credit-worthiness of any particular sector in the latest downturn, either. Both then and now, large exposures to below-investment-grade-rated instruments still offer an obvious clue that a fund is taking outsize credit risk. Most of the short-term bond funds that got hit the hardest during the recent sell-off had more than 10% of their portfolios in junk-rated issues, for instance. Sizable nonrated stakes are also worth questioning. While the lack of a credit rating doesn't necessarily equate to more risk, it can sometimes be a sign of less liquidity, especially since many bond indexes and institutional investor mandates will exclude bonds that aren't rated by a major ratings agency, thereby reducing their buyer base.

4) … then look a layer deeper. Bonds with the same credit ratings don't have the same risk characteristics, however. All else equal, a fund with a 50% exposure to AAA rated issues entirely made up of U.S. Treasuries does not have the same risk-profile as one that invests 50% in AAA rated commercial mortgage-backed securities or collateralized loan obligations. Morningstar's fixed-income manager researchers wouldn't bat an eye about the former, but the latter would raise concerns about concentration risk in these credit-driven sectors.

Further down the ratings spectrum, distinctions can be even harder to draw without access to more-granular data than asset managers typically publicize. As analysts, this is something we routinely scrutinize. For example, our fixed-income manager researchers don't like to see large exposures to securitized debt with mid- and lower-quality ratings in short-term and ultrashort bond portfolios. An index-eligible BBB rated corporate bond issued by a large company has plenty of natural buyers, even in the event it gets downgraded to below-investment-grade (plenty of high-yield bond managers have scrambled to get exposure to bonds issued by Kraft Heinz and Ford since they lost their investment-grade ratings earlier this year). But most BBB rated structured credit--while a staple of some leveraged hedge funds--represent subordinated claims on an underlying pool of loans, aren't present in any widely followed indexes, and tend to be held in mutual funds in only very small amounts. Even if the bonds ultimately recover without experiencing any loss of principal, these characteristics make them more vulnerable to suffering price declines when liquidity evaporates.

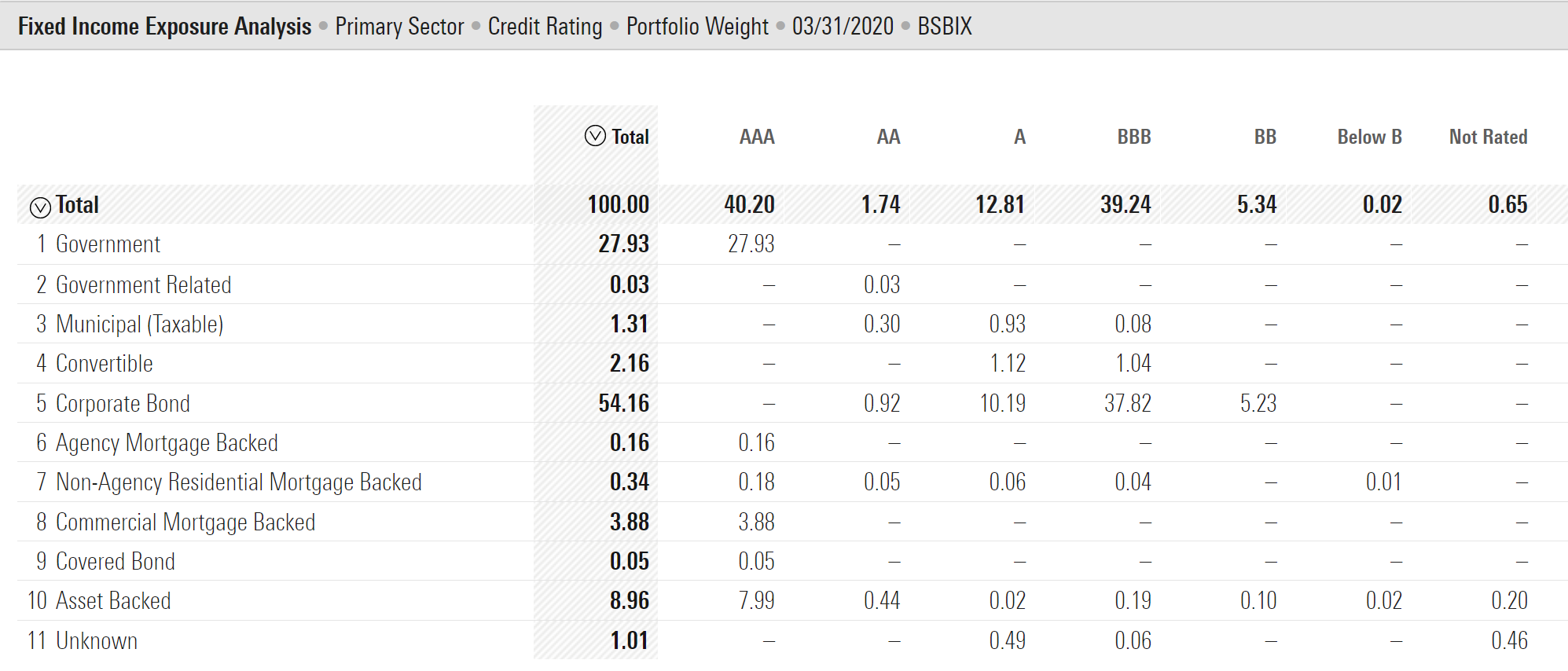

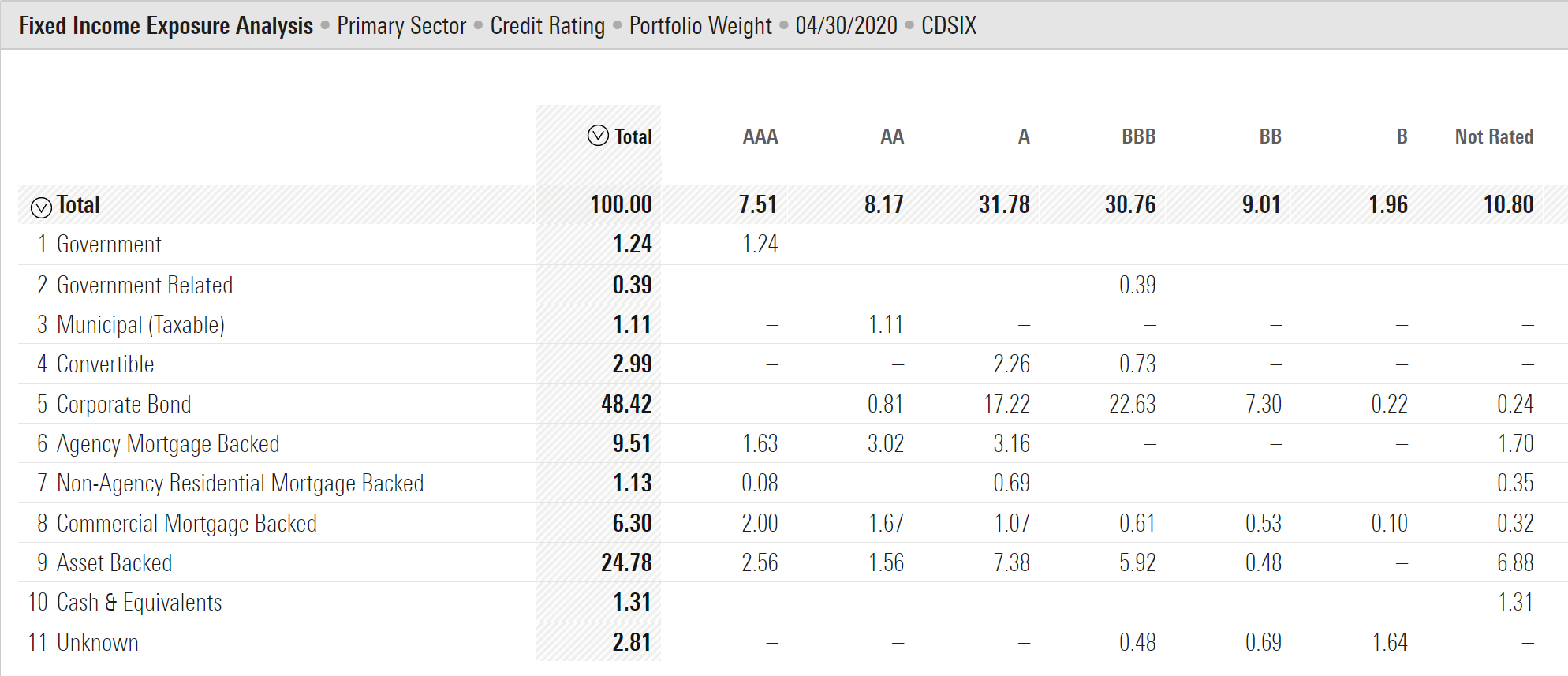

Knowledge Is Power Managers routinely disclose fund-level credit-quality exposure breakdowns to the public, but it's a lot harder to find out how a fund's exposure to a certain credit-ratings tier breaks out along sector lines. Fortunately, we recently rolled out a new Fixed Income Exposure Analysis, or FIEA, component for Morningstar Direct and Morningstar Office users to help investors answer these questions (elements of this will be available in fund reports on Morningstar.com and other products later this summer). To illustrate the importance of getting a more detailed understanding of how different sectors contribute to a portfolio's credit-quality exposure, I used this tool to compare the credit-quality breakdowns--by sector--of the latest portfolio for a fund that held up relatively well in March 2020, as well as one that performed poorly.

Gold-rated Baird Short-Term Bond BSBIX was among the category's better performers in the pandemic-related sell-off. Its 2.9% loss from Feb. 20, 2020, through March 23, 2020, was less painful than roughly two thirds of its distinct short-term bond competitors', and its 2.9% gain for the year to date through June 30 landed just outside the peer group's best quartile. The following view from the FIEA tool highlights many of the attributes we like to see in a prudently managed short-term bond fund. It has a healthy 28% stake in U.S. Treasuries to provide a safety cushion. With 39% and 5% in bonds rated BBB and BB, respectively, the team is clearly willing to take some risk. However, it's comforting that these exposures consist predominantly of corporate-bond holdings (this team gravitates toward larger, more-liquid corporate issuers) and not relatively esoteric structured credit. The fund's modest CMBS and ABS stakes, meanwhile, are almost entirely AAA rated.

Source: Morningstar Direct.

By contrast, the latest portfolio of Neutral-rated Calvert Short Duration Income CDSIX, which trailed roughly 85% of its distinct short-term bond peers during the sell-off with an 8.3% loss, exhibits a few warning signs. It holds very little in the way of a buffer in Treasuries or cash. While it does show 9.5% in agency MBS, this includes a stake in agency credit-risk-transfer securities, which do not enjoy the backing of the U.S. government and are exposed to losses in the underlying mortgage loan pools. For this reason, it's more useful to think of them as nonagency MBS exposures, though in this table their presence is signaled by agency MBS exposure that is rated below AAA. In other structured credit exposures, the managers show a willingness to invest down the capital structure in bonds rated A and BBB, which can heighten liquidity risk.

Source: Morningstar Direct.

Conclusion Fortunately, most bond investors have come through the market's COVID-19 related sell-off with lighter damage than one might have expected. But while bonds are generally viewed as the safer element of investor portfolios, the bond market has a habit--and history--of wooing investor dollars with products that promise a little extra return while quietly generating a lot of extra risk. Some investors paid even more dearly for that kind of risk during the 2008 financial crisis, and while it's impossible to know when or how bad the next one will be, it's certain that there will be a next one.

As long as the bond market offers those kinds of propositions, investors will want to remain vigilant in avoiding them. We're always looking for better ways to help in that pursuit and hope that Morningstar's new Fixed Income Exposure Analysis component can do just that.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/07-25-2024/t_56eea4e8bb7d4b4fab9986001d5da1b6_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BU6RVFENPMQF4EOJ6ONIPW5W5Q.png)