Are Dividend Funds All That?

Looking closely at today’s investment darlings.

Hot Commodities

Dividend funds are in the spotlight. Their investment approach—which can mean anything from owning stocks that pay very high dividends to holding companies that distribute humble but growing payouts—has long existed, but until recently, such funds garnered little attention. That has changed. In the past 10 days alone, three features on the topic have appeared.

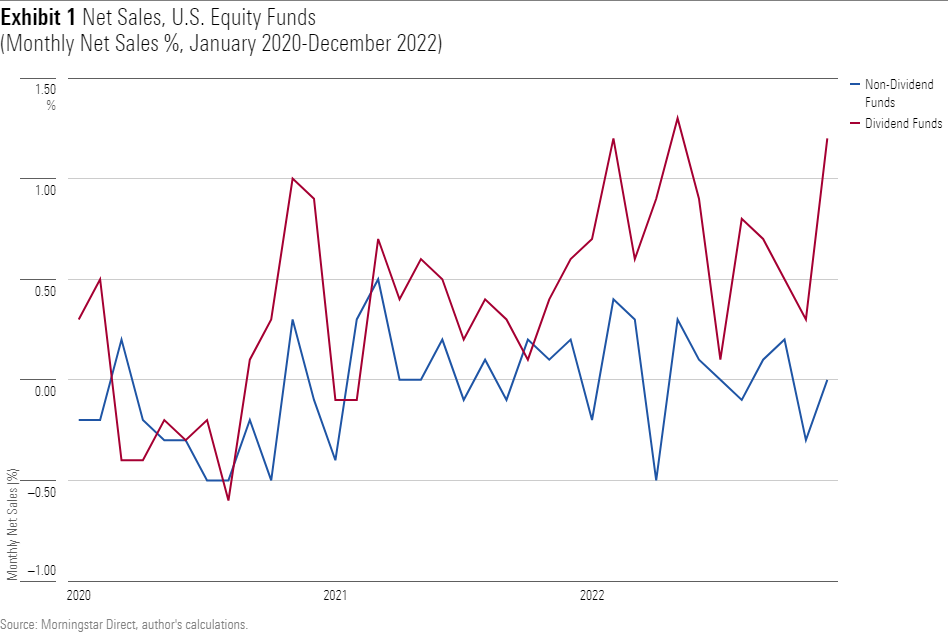

The articles reflect shareholder demand. The graph below depicts monthly net sales over the past three years, expressed as a percentage of starting assets, for 1) the 128 U.S. equity funds that have dividend in their names, and 2) the 2,560 that do not. Since autumn 2021, those lines have sharply diverged.

Hot (Relative) Performance

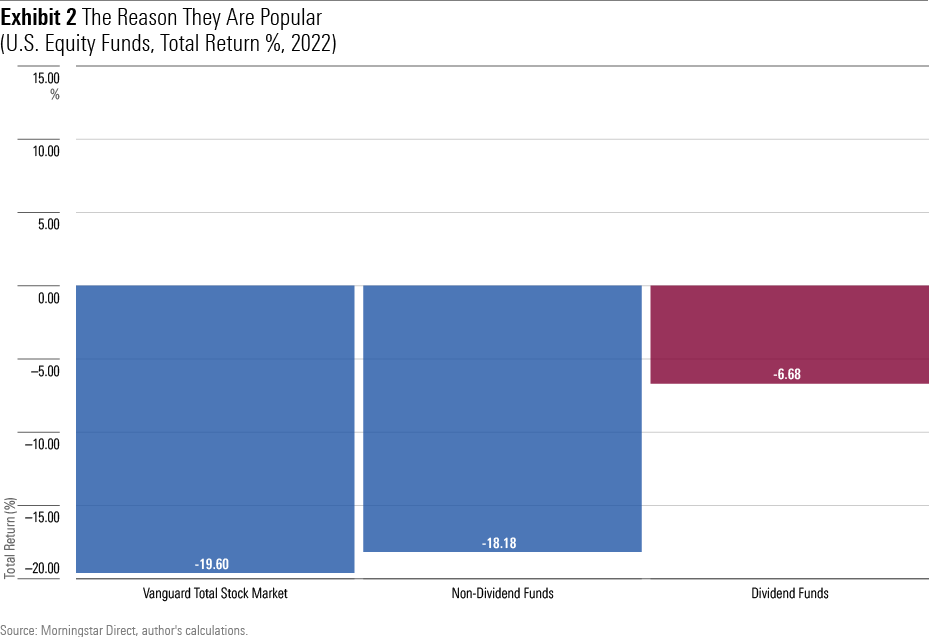

Dividend funds have attracted interest for the same reason that every other fund strategy suddenly becomes popular: performance. While U.S. equities, as represented by Vanguard Total Stock Market Index VTSMX, shed 19.6%% during calendar 2022, and nondividend equity funds fared similarly, the average loss for dividend funds was much lower, a moderate 6.68%.

Dividend funds better withstood the slump because they hold fewer technology stocks than the index and because the securities they do own sell at a lower cost and are of better quality. The price multiples of the companies held by dividend funds are below the stock index average, while their Morningstar Financial Health Grades are higher. They are, for the most part, stable businesses—organizations that appeal during bear markets.

Bear-Market Results

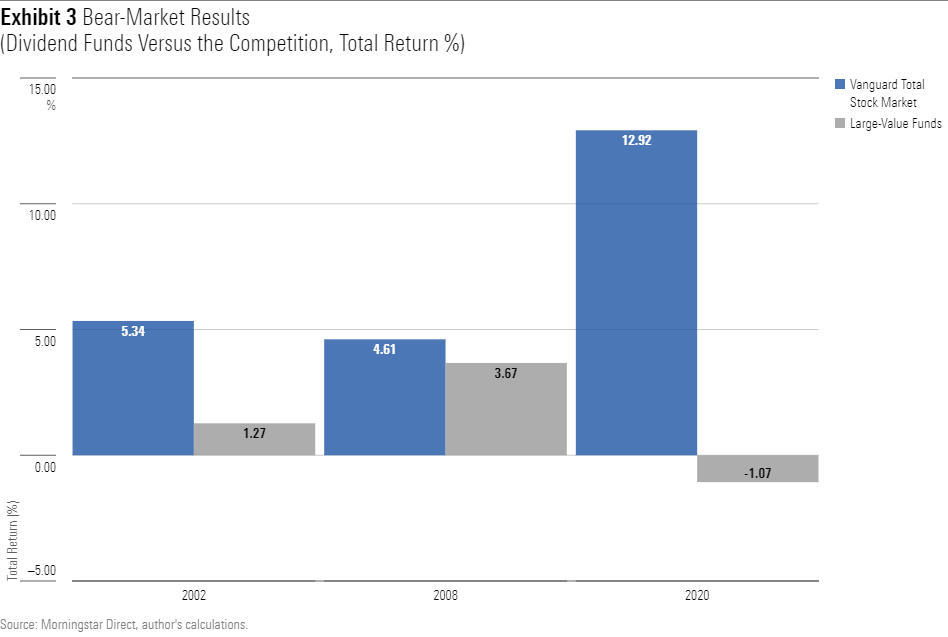

Which raises the question: Did dividend funds perform as well during the previous bear markets of 2008 and 2002? The question is rhetorical. Obviously, they did not, because had they so powerfully resisted either of those downturns, they would have already gained their fame. But perhaps they still fared relatively well.

We will test that proposition in two ways. First, by comparing the bear-market returns for dividend funds against those of Vanguard Total Stock Market Index. (There is no need to evaluate the average return for all U.S. equity funds, because they closely tracked the index.) A second comparison will be with large-value funds, as their investment universe overlaps with dividend funds’. Positive figures indicate that dividend funds were superior, with negative outcomes signaling the reverse.

To no great surprise, dividend funds were less heroic during the previous two declines. Still, they did offer some down-market protection. Investing in businesses that are established enough to pay meaningful dividends, while (usually) possessing the financial strength to continue those payments even through recessions, does alleviate stock market pain. The same, though, may be said of large-value funds, which lagged dividend funds in 2002 and 2008 before holding up even better last year.

Bull-Market Gains?

So far, our discussion has exclusively concerned capital preservation. That, however, is only half the story. After all, cash always resists bear markets (in nominal terms), yet nobody recommends Treasury bills as long-term investments. (Short Treasuries may serve as a portfolio buffer, but that is a different issue.) And dividend funds are less defensive yet, reliably losing when equities fall. To justify their existence, then, they must post acceptable gains when equities rise.

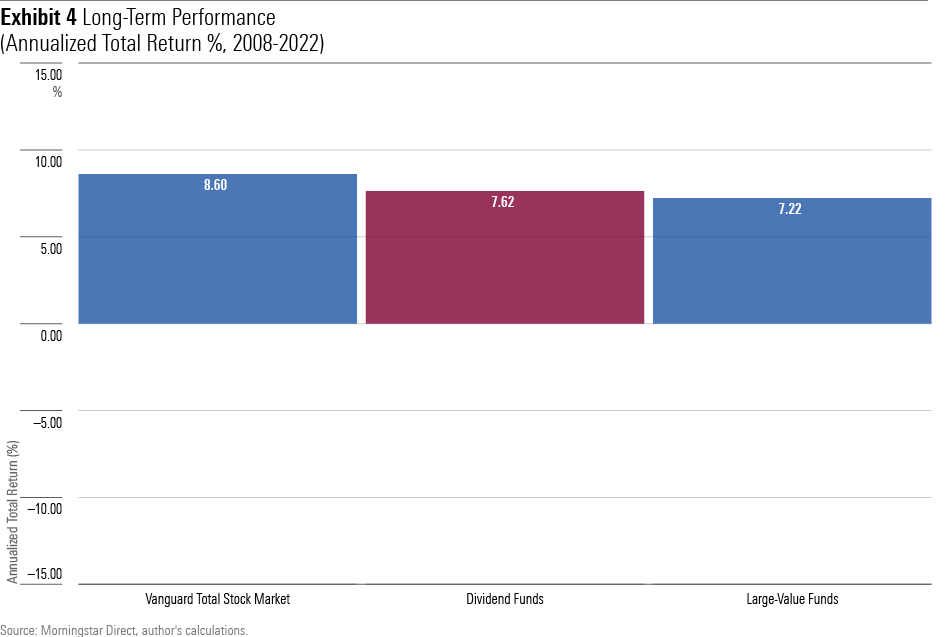

That task they have accomplished, as their 15-year total returns aren’t far off those of Vanguard Total Stock Market Index and sit just above that of large-value funds.

About half the return difference between dividend funds and Vanguard’s mammoth index funds owes to expenses, with the average dividend fund costing 70 basis points more per year. The remaining gap comes from trailing during the bull markets. Dividend funds do concede their bear-market advantage when equities rally. But not by much.

Ongoing Income

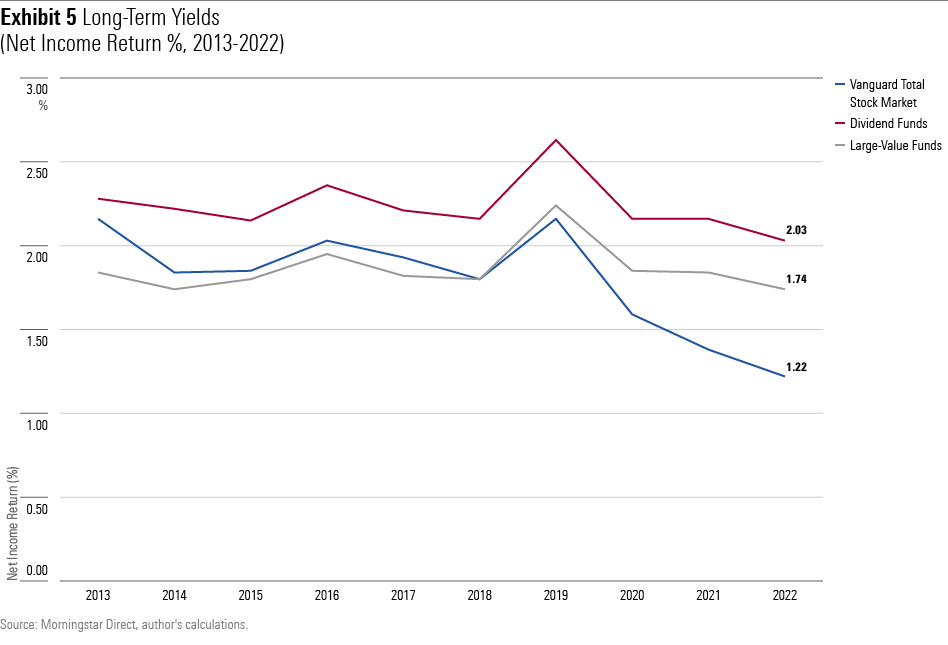

A final consideration is the promise on the funds’ label: dividends. How much more income do they pay than their investment rivals? As shown in the exhibit below, that answer varies. Ten years ago, the average dividend fund yielded barely more than Vanguard Total Stock Market Index but easily surpassed large-value funds. Today, those positions are reversed: Large-value funds have narrowed the gap, while Vanguard’s fund has slipped.

Overall, though, dividend funds have consistently outyielded their rivals. To be sure, the average conceals major differences. Some that seek high current income boast yields in excess of 4%, albeit at the cost of future dividend growth. Meanwhile, the most growth-oriented funds distribute no income at all, after bankrolling their expenses. (Personally, I would hesitate to sell a “dividend” fund that paid no dividends, but that could be just me.)

Summary

Count me impressed. Bear-market heroes usually flop. Market-timing funds were all the rage after Black Monday 1987 but faded into obscurity a few years later. Their cousins, asset-allocation funds, struggled similarly after the technology-stock crash of the early 2000s. Attention then shifted to liquid-alternatives funds in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, and most of them have since languished.

But dividend funds are not gimmicks. They have stood the test of time; of the 33 that existed when this millennium began, 24 still operate today—a relatively high survival rate by fund standards. In addition, the group’s performance has been fine. In fact, they have bested one of the industry’s stronger fund categories, large-value funds, by posting slightly higher returns, lower volatility, and stronger yields. (Although for those investing through taxable accounts, the latter may be a decidedly mixed blessing.)

My next column on this topic, to be published one week from today, will name names, by listing the best offerings within each subgroup of dividend funds.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors own shares in one or more securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DOXM5RLEKJHX5B6OIEWSUMX6X4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)