Should You Follow Your Fund Manager Who Moves to a New Firm?

When your fund manager leaves to a new firm, it can be tempting to follow. But historical evidence shows that you should think twice before taking the leap.

Remember when Bill Gross left Pimco in 2014 to join Janus Capital Group? Even if you weren’t invested in any of the funds Gross managed at Pimco at that time, you probably noticed the fuss around it. High-profile or not, there are plenty of managers leaving their firm to join a competitor or to set up their own investment firm. As a fund investor, there is a good chance that you have experienced this with a fund you own. It usually takes time to evaluate the situation. My colleague Christine Benz wrote a great article on the questions you should ask yourself to decide whether you should stay put. But if you’ve decided to sell the fund, should you follow your manager to the new firm?

Historical Evidence From the U.S. and Europe

To answer that question, we compiled a dataset of fund managers changing shop going back to the 1990s in the United States and 2000s in Europe by looking at the historical tenures in the Morningstar database and cross-checking with firm names. Funds managed by more than two managers (three managers and more) were excluded, as manager departures are less of an issue for funds with large teams. The performance results more from a collective effort, so it’s difficult to split into individual contributions, which we needed for our tests. Further, we only included funds housed by firms that are covered by Morningstar’s Manager Research team. Our knowledge of these firms and their history facilitated the qualitative checks we needed to perform. For each manager, we picked the fund where they had the longest track record, requiring at least three years of tenure at the old firm and three years at the new firm. That left us with 518 manager departures to look at.

We then calculated performance using monthly returns before fees (“gross returns”) to isolate the potential value added by the fund manager. We used Jensen’s alpha calculated with the fund’s Morningstar Category index as our measure of risk-adjusted performance.

Fresh Starts Often Result in a New Manager Bounce

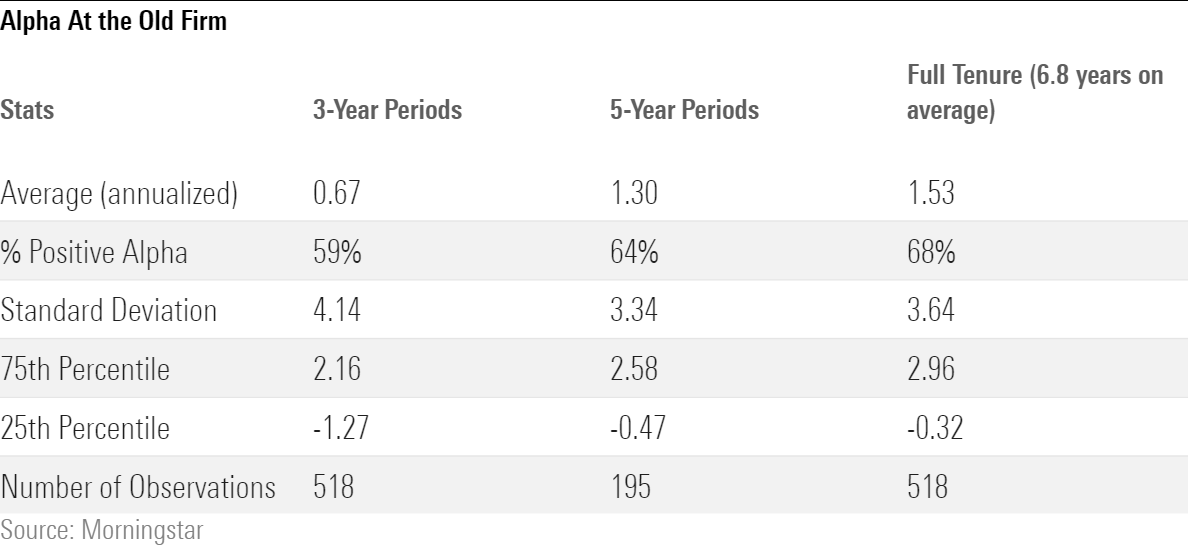

Most fund managers who left their firm (voluntarily or involuntarily) had built an attractive record, which makes it tempting to follow them to their new house. Looking at their full tenure at the old shop, they produced an average annualized gross alpha of 1.53%, and 68% of them had a positive alpha.

Shorter periods (three- and five-year) also paint a rosy picture for these fund managers. This compares favorably with long-term gross-of-fees alpha generated by U.S. mutual funds—we found that, in the past 20 years, the average rolling five-year gross alpha was 0.85%. (Gross-of-fees alpha on 12,750 surviving and dead U.S. mutual funds, both equity and fixed income, from June 2002 to June 2022; alpha measured with the one factor CAPM model using Morningstar Category Indexes.)

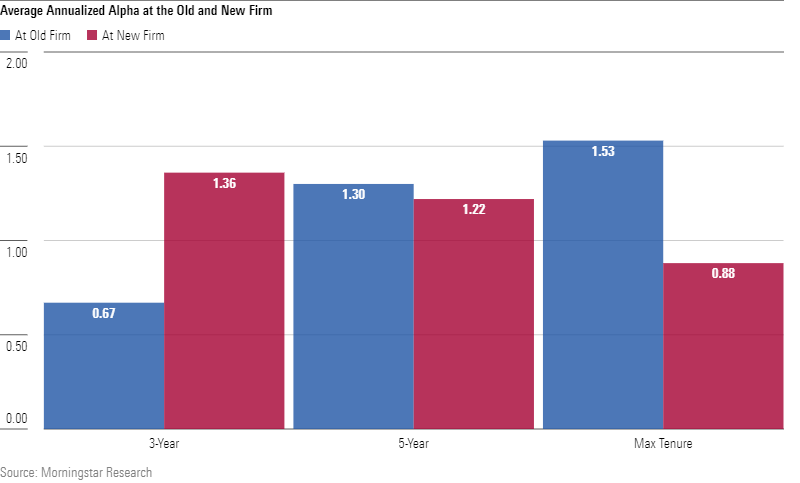

In the initial years after their fresh start, fund managers often thrived. We observe a significant uptick in average alpha from the old firm (0.67%) to the new firm (1.36%) when looking at three-year periods (last at old and first at new). There are strong incentives for both the asset manager and the portfolio manager coming onboard to show good results rapidly. The new firm probably provides resources and support to make the transition successful.

On the portfolio manager’s side, the motivation and work intensity are surely high to show their worth and mettle to the new company. They are also benefiting from managing less money in the first years at their new house, making it potentially easier to outperform (the average fund size at the new firm is 30% lower than at the old firm). A stronger explanation, though, is these managers are still surfing on the successful investment style that led them to be hired in the first place.

Everything Evens Out in the Long Term

Based on our results, this success does not often last. The increase in alpha we observe initially fades away when we lengthen the horizon and look at the five-year periods when the average alpha is broadly similar at the old and new firm. The manager is also managing more and more money, possibly lowering alpha potential. When looking at the performance over the full tenure before and after departure, the level of excess return drops significantly to an 0.88% annualized alpha from 1.53%.

However, what if investors had stayed with the manager’s old fund? This didn’t seem to be a better idea. On average, alpha of the manager’s old fund after the departure is lower compared with how managers performed at their new house. In the five-year periods after the departure, the fund managers at their new fund outperformed their old fund (under new management), on average, by 52 basis points annualized.

Past Performance Doesn’t Dictate Future Success

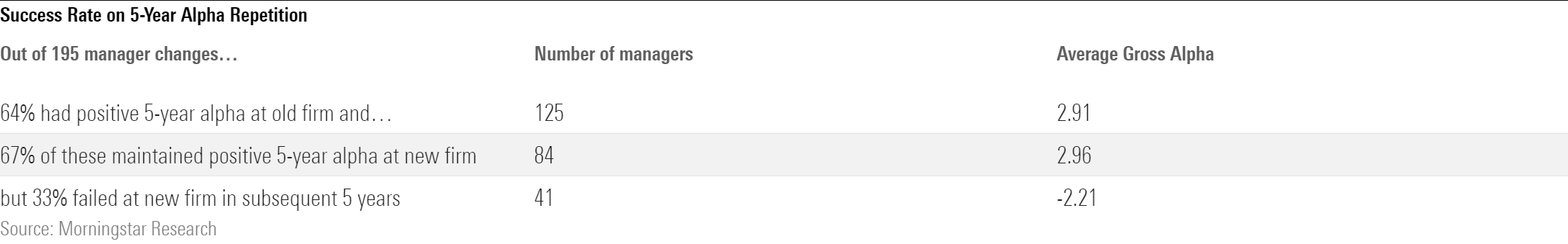

Another interesting angle was to look at success rates by measuring the proportion of fund managers who delivered a positive alpha at their first employer and maintained a positive alpha at their new firm. Based on the five-year records, two thirds (67%) of these “successful managers” repeated their accomplishment at their new firm. Isn’t that a sign of encouragement to follow the manager? Not necessarily. The statistics don’t include the managers who were not able to build a five-year record at their new employer. Out of the 335 managers with a five-year record at their old firm, 140 (42%) were not able to finish a five-year record at the new firm. Inclusion of these managers lowers the success rate to 35%. Also, it would have been a very risky bet for investors to go with the apparent winners just based on their first track record. One third of these successful managers failed to repeat their past success, with a negative gross alpha of 2.2%.

Numerous academic studies, as well as our research at Morningstar, have proved that past performance is not a reliable predictor of future performance. Could manager changes make an exception? That is unlikely. Outperformance is difficult, and managers’ alphas were far from linearly lined up between the old and the new firms when looking at our sample. The statistical connections we found were tenuous at best. In other words, alpha generated at the first firm doesn’t explain much of the variation in the alpha generated subsequently.

Signs to Consider Following a Fund Manager

There are a few managers who successfully transitioned to their new firm and continued to generate excess returns for investors. Based on our experience, there are several other factors influencing a successful transfer that investors should carefully consider:

- Alignment of Investment Philosophy: It’s not very common for a manager’s past track record and investment philosophy to be completely and directly applicable to the new strategy. The new firm may have a different house investment process or approach. This can affect the transfer of investment skills. The closer the two investment philosophies are, the better.

- Support and Resources: It’s important to compare the resources at the former employer and new employer. The analytical support, in-house expertise, and tools that fund managers used at their previous firm have likely played a role in generating excess return. The new firm should provide a comparable or better level of resources, such as research and analytical tools, to support the fund manager’s investment approach. Without adequate resources, managers may not be able to implement their investment strategy effectively.

- Cultural Fit: Fund managers need to fit in with the new culture and values to be able to transfer their skills effectively. Firms with good stewardship practices have better foundations to make the transition a success. Such firms operate within their circle of competence, do a respectable job of aligning manager interests with those of investors in their funds, and charge reasonable fees. It can be a good idea to look at how a firm has handled fund manager integration in the past.

- Team Dynamics: If fund managers are joining an established team, they will need to adapt to the existing team dynamics. Also, if the manager had previously evolved in a star manager system, it can be difficult if teamwork is emphasized at the new firm. Overall, positive team dynamics likely increase the chances that managers can apply their skills effectively.

- Fees: These are a critical part of the equation. If fees charged at the new fund are significantly higher than at the previous fund, it can be a dealbreaker. No matter how talented the portfolio manager is and how well the transition looks from the get-go, if fees are too high at the new shop, investors may lose in the long run.

Answering the points discussed above should help you build confidence, but you should still be careful when confronted with a manager departure. Since it is difficult to predict the outcome of a change with certainty, it may be wise to stay on the sidelines for a period of time and observe the performance of the manager at his new firm before jumping on, especially if you have doubts.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6NPXWNF2RNA7ZGPY5VF7JT4YC4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/RYIQ2SKRKNCENPDOV5MK5TH5NY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)