Not All Robo-Advisors Are Created Equal

Investors should do their own research, as recommended portfolios can vary—a lot.

We recently published our second annual survey of digital investment advice providers available to individual investors, the 2023 Robo-Advisor Landscape. The report includes our analyst assessments of 18 leading robo-advisors in the United States, extensive data tables on a total of 20 robo-advisors, and several sections discussing industrywide trends.

As a follow-up to the report, I asked Morningstar summer intern Brian Paoli to do some additional sleuthing. I gave him a set of data and assumptions for two hypothetical investors, one who wants to make a down payment on a new house in seven years and another who is investing for retirement in 25 years. The results were eye-opening. In fact, while robo-advisors are supposed to make investing easier, our findings make it clear that investors shouldn’t sign up for digital investment advice without kicking the tires first to understand exactly what they’ll be getting.

The Setup

Robo-advisors typically start by asking investors a series of questions about their financial goals and level of risk tolerance. They then feed this data into an advice engine (basically a software program that incorporates a series of algorithms) that recommends one of several portfolio options with a suitable risk level, typically ranging from conservative to aggressive. The questions vary depending on the provider, but most ask for some of the same basics to assess client goals, time horizons, and risk-tolerance levels. For our test, we came up with two separate profiles for hypothetical investors with two distinct financial situations and investment goals.

Investor A: Saving up for a house. We imagined a person who is 30 years old, has a salary of $80,000, and wants to accumulate $50,000 for a down payment in seven years. We assumed existing assets of $10,000 in an emergency fund, $50,000 in retirement savings, and $10,000 in a taxable account, with the latter amount being used to fund the robo-advisor portfolio. We also assumed additional contributions of $250 per month.

Investor B: Investing for retirement. Our other hypothetical investor is 40 years old, has a salary of $100,000, and wants to accumulate $1 million for retirement in 25 years. We assumed existing assets of $10,000 in an emergency fund and $100,000 in an IRA, with the IRA assets earmarked as an initial investment in the robo portfolio. We assumed additional contributions of $500 per month.

For both investors, we assumed a moderate risk tolerance, which is the level of risk investors can endure to achieve their investment goals. To assess this, robo-advisor questionnaires typically focus on investors’ level of investment experience, how they feel about risk in general, or how much they would be willing to lose for the chance of a given investment gain. Every set of questions is different, but we tried to choose responses that would fit a middle-of-the-road level of risk tolerance. (In practice, this usually meant selecting the middle option when presented with a range of potential answers.)

The Results

We weren’t able to get sample recommendations from every provider. Of the 20 robo-advisors included in our study, only seven allow investors to go through the risk-tolerance process without setting up an account or email registration. This lack of transparency is unfortunately pretty common in the digital advice industry. Investors often can’t access basic information about how their money will be invested until they actually sign up with a provider. That makes it impossible to determine ahead of time whether the portfolio would be a good fit.

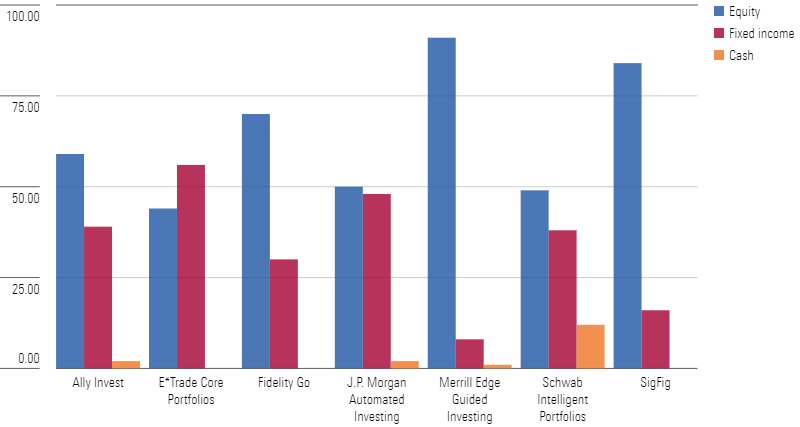

Among the seven providers we were able to view, portfolio recommendations varied widely.

For investor A, the level of recommended equity exposure ranged from a high of 91% (Merrill Edge Guided Investing) to a low of 44% (E-Trade Core Portfolios). Cash allocations were generally low, although Schwab Intelligent Portfolios, which paid a $187 million settlement in 2022 for previous disclosure practices related to its cash allocations, recommended a 12% stake in cash. Subasset allocations also spanned a broad range. Most of the providers recommended a relatively straightforward mix of exchange-traded funds focusing on U.S. large-cap stocks, international developed markets, and emerging markets. Ally and E-Trade also included ETFs focusing on small- and mid-cap stocks. Schwab’s subasset allocation was by far the most complex; its recommendations included domestic and international stocks spanning both large- and small-cap stocks, five different fundamental index ETFs that tilt toward value stocks, and small positions in both U.S. and non-U.S. REITs.

Investor A Recommendations

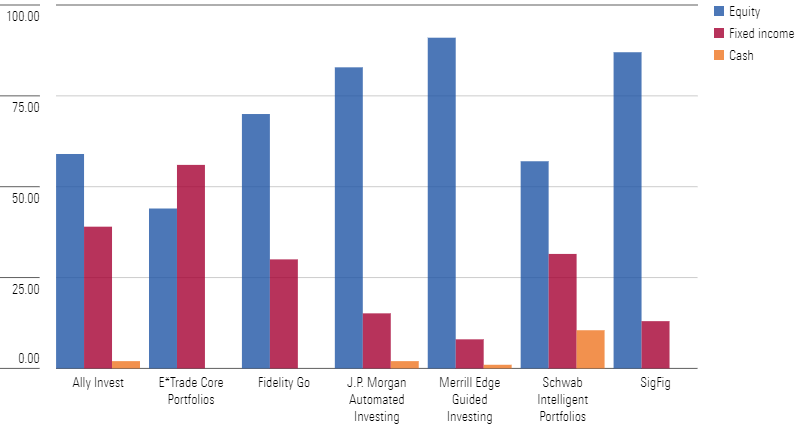

For Investor B, the level of recommended equity exposure also ranged from a high of 91% (Merrill Edge Guided Investing) to a low of 44% (E-Trade Core Portfolios). That’s a surprising outcome, given that Investor B was saving for a goal with a significantly longer time horizon. As in the previous case, Schwab Intelligent Portfolios had the highest recommended cash allocation, at 10.5% of assets. The sub-asset-class allocations for all of the providers were similar to those recommended for investor A.

Investor B Recommendations

Other Findings

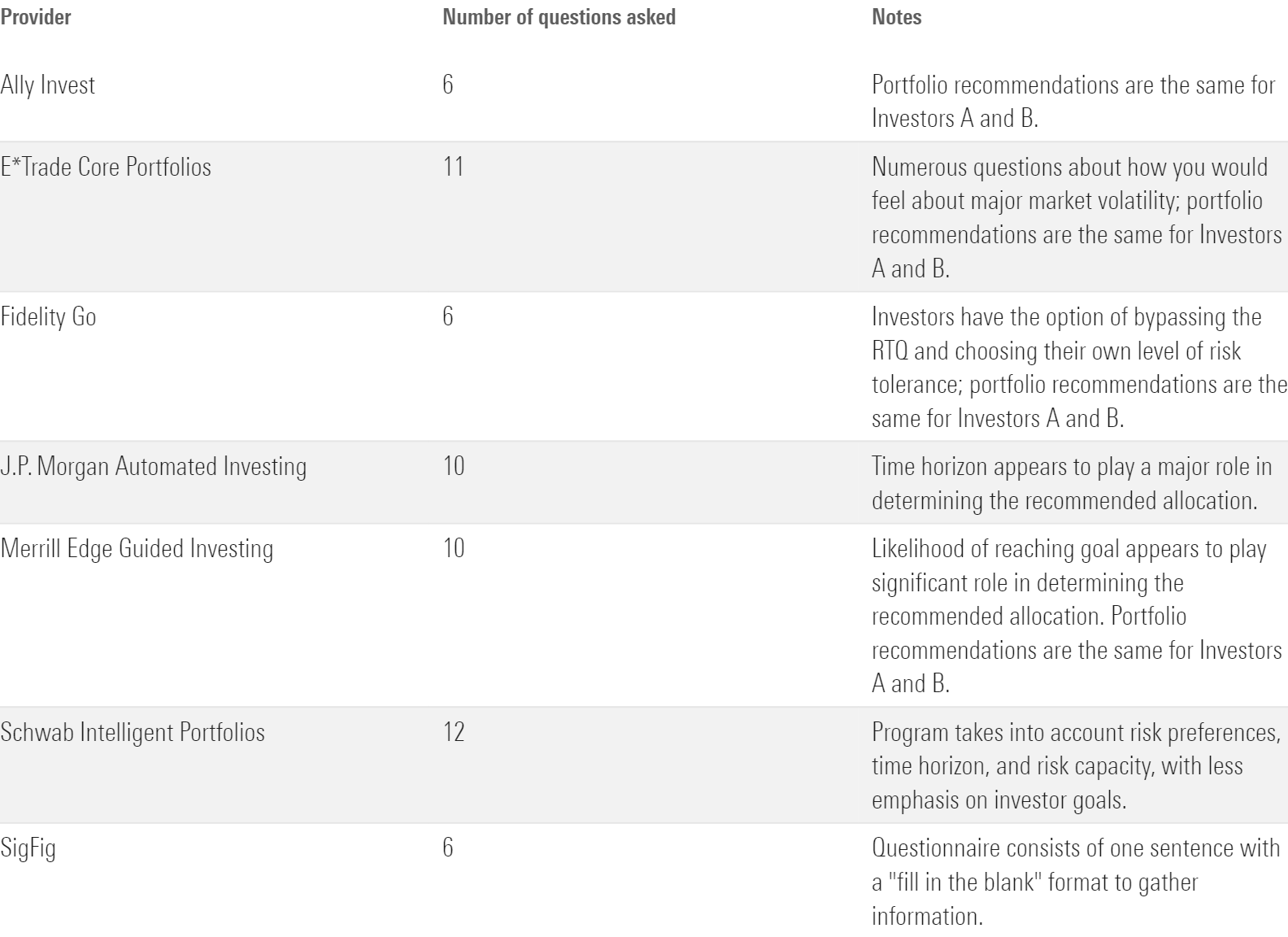

As shown in the table below, the risk assessment process also varied by provider. The risk-tolerance questionnaires for Ally and Fidelity Go consisted of only six questions, and Fidelity allows investors to self-assign a risk-tolerance level and bypass the questionnaire altogether. SigFig asked for similar information in an even more streamlined “fill in the blank” format with one sentence.

Other Robo-Advisor Findings

At the other end of the spectrum, E-Trade Core Portfolios and Schwab Intelligent Portfolios asked for about twice as much information. Schwab was also one of the few providers to assess risk capacity, which measures a person’s ability to take risks given their financial assets and other resources, in addition to risk tolerance, which measures an investor’s preferences and subjective willingness to take risks.

The Biggest Surprise

The most surprising finding from our research: Four of the seven robo-advisors (Ally Invest, E-Trade Core Portfolios, Fidelity Go, and Merrill Edge Guided Investing) recommended the exact same portfolio for both investor profiles.

This doesn’t really make sense given that the specified time horizons differed by 18 years. An investor with a 25-year time horizon can afford to take on significantly more equity risk than an investor with a seven-year time horizon and arguably should take on more equity risk to help build retirement assets over time.

Without having access to the underlying algorithms that led to the recommended allocations, I can only speculate that these four providers place a heavy emphasis on the investor’s assessed level of risk tolerance instead of the planned time horizon. This approach may increase the odds that our hypothetical investor would hold on to the portfolio during market drawdowns but may not be optimal in terms of funding a specific goal.

Conclusion

Robo-advisors have one key purpose: to simplify and automate the investment process. However, our research underscores the fact that the resulting portfolios often vary. The upshot is that while robo-investing delivers on its promise to automate the investment process, investors should still do their own research and make sure they’re comfortable with the recommended portfolio before signing up with a specific provider.

Brian Paoli contributed to this article.

3 of the Best Robo-Advisors, and One of the Worst

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BL6WGG72URAJJJCPC4376SZKX4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZHBXSNJYDNAY7HDFQK47HGBDXY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/2TT3THVKOJAKBFGHCCRTVPNEQ4.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)