How To Optimize Future ETF Income

Investors must look beyond an exchange-traded fund’s current yield when building future cash streams.

Investors may like income investing for its consistent stream of cash payments. Others may use income strategies as an indirect way of targeting quality companies with reliable cash flows or to boost returns during sideways markets. The advantages are clear for retirees or those relying on investment income to pay bills.

Income strategies are reasonably reliable and allow investors to plan around their expected income. Operationally, it’s easy to cash checks from dividends and interest. On the other hand, selling investments to generate income requires trading and settlement before the proceeds are available to use or transfer out of the account.

But biases and mental accounting creep into how investors view income. It can feel like a bonus: Cash hits the investor’s account, but their investment principal remains intact.

The reality is that income can be overrated. A dividend fund cuts investors a check, but the fund’s price drops proportionally, leaving no mathematical advantage. And other income-producing assets, such as bonds, come with higher tax rates than long-term capital gains. Income reduces the flexibility of investors to maximize tax efficiency, and not all income is created equal. Focusing too much on yield leads investors to suboptimal strategies.

The value of income is in the eye of the beholder. But in taxable accounts, income almost always comes with a cost. In this article, I will help clarify the trade-offs at stake for income investors to help inform better investing decisions.

Wading Through Different Income Streams

Investing income comes in several forms. The most common are dividends, interest, money market accounts/certificates of deposit, REITs, covered-call strategies, and selling principal. Each comes with its own risk profile, payout strategy, and tax implications.

Dividends

Dividends can be a great source of income. But fishing in the wrong pool for dividends can leave investors empty-handed.

There are two central decisions when pursuing dividend strategies: 1) balancing yield and risk and 2) seeking out qualified dividends. Our top-rated dividend exchange-traded funds do both. They achieve the former by minimizing the risk of value traps with low-turnover strategies that meet the requirements for qualified dividends. For a dividend to be qualified, the stock must be held for more than 60 days in the 121-day period that began 60 days before the ex-dividend date. Nonqualified dividends are taxed at a higher rate, so seeking out qualified dividends is a no-brainer.

Bond Interest

The Federal Reserve has hiked rates by 5 percentage points in the past year and a half. The silver lining for investors is that the days of “there is no alternative” to stocks is over. Short-term bonds provide solid yields again. The bad news for bondholders is that interest will become a bigger piece of the return pie for bonds, which means a higher tax rate versus long-term capital gains from price appreciation. Bond investors should expect to share their proceeds with Uncle Sam unless they hold their funds in tax-advantaged accounts or buy tax-exempt municipal-bond funds.

Retirees depending on a consistent source of income may be frustrated by recent interest-rate volatility. Bond funds typically don’t hold bonds to maturity; instead, they tend to lock in losses as they rotate into higher-yielding bonds when interest rates rise.

Investors keen to tamp down interest-rate volatility could employ an alternative strategy known as a bond ladder using defined-maturity ETFs. ETFs targeting a specific maturity don’t swap shorter-maturity bonds for longer ones to maintain a specified duration. Instead, they hold a specific type of bond—like Treasuries, corporate bonds, or high-yield bonds—that mature in a given year. For example, iShares iBonds Dec 2025 Term Corporate ETF IBDQ holds investment-grade corporate bonds that mature in 2025. The market for these ETFs is dominated by iShares iBonds and Invesco BulletShares, and they cost just a few basis points more than the cheapest bond funds available.

Clipping coupons with a bond ladder reduces volatility, but it comes with a cost: Inflation could erode the purchasing power of income from the bond ladder. I encourage those interested in learning more to read “Bond Ladder ETFs Can Help Investors Climb Higher” by my colleague Saraja Samant.

Covered Calls

Covered-call strategies own a security, then sell call options against it to generate income. Higher income could help fill coffers or create a theoretical buffer were the underlying security to fall in price. But selling an at-the-money call limits the strategy’s upside at the premium collected from the call option. This trade-off effectively juices yields, with some covered-call ETFs clocking in at an over 10% trailing 12-month yield as of June 2023.

But there are several strings attached to their high yield. These strategies often come with significantly higher costs than purchasing the underlying security alone. And markets tend not to follow a normal distribution of returns, instead exhibiting the propensity for extreme price moves, or “fat tails”—a topic Eugene Fama wrote about in his dissertation 50 years ago that remains true today. Covered-call strategies exclude the good fat tail—unusually strong market returns—but retain exposure to the bad fat tail—significant market drawdowns.

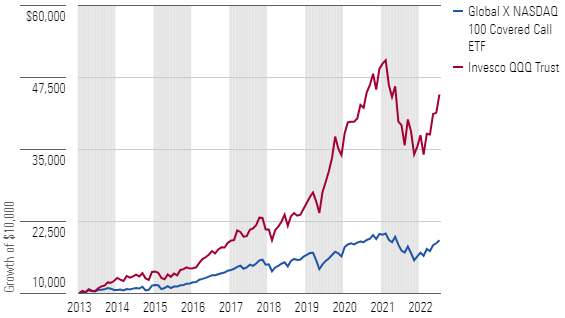

The opportunity cost is immense for covered-call strategies. A primary example is Global X Nasdaq 100 Covered Call ETF QYLD, which launched in December 2013. Since inception, it has averaged a trailing 12-month yield of more than 10%. But even after reinvesting those dividends, it has still lagged Invesco QQQ Trust QQQ—which tracks the Nasdaq 100 Index—in total return by 250-plus cumulative percentage points from December 2013 through May 2023.

Covered Calls Undermined Nasdaq 100 Index Performance

Keeping the Most of What You Earn

Morningstar’s ratings process pits funds against one another in terms of risk-adjusted total return, which assumes all income from an investment is reinvested in the fund. What total return fails to account for is the tax implications of various income streams in taxable accounts.

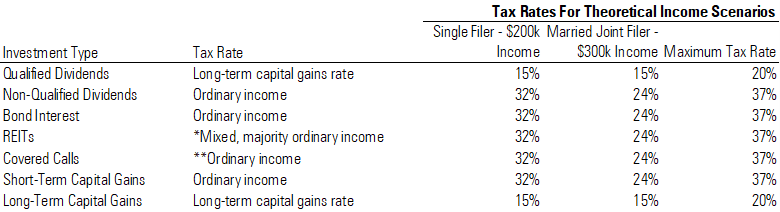

Taxes are a critical consideration for income strategies. Qualified dividends and long-term capital gains come with the lowest tax rates. Most nonqualified dividends, bond interest, REIT dividends, derivative income, and short-term capital gains are treated as ordinary income and are taxed at the investor’s marginal tax rate, which is always higher than the long-term capital gains rate. The table below details the tax implications for different sources of income and gives a real-life example for a single filer making $200,000 per year and a married joint filer earning $300,000 annually.

Tax Implications of Different Income Assets

The difference between ordinary income tax rates and long-term capital gains rates can reach 20 percentage points. This has major implications for investors, especially regarding high-yielding securities like covered-call strategies and REITs. But income investors lose ground even when they receive the favorable tax rate for qualified dividends.

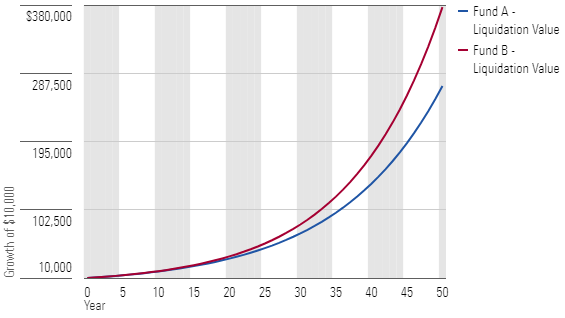

Consider an investor at the maximum tax bracket who buys two theoretical funds—Fund A and Fund B— that each earn 8% annually. Fund A yields 5% in qualified dividends, while Fund B yields 0%. The chart below demonstrates the tax drag over the long run despite qualified dividends and long-term capital gains sharing the same 20% maximum tax rate. All else equal, deferring taxes is the optimal strategy.

Deferring Taxes Can Make a Big Difference

A Path to Higher Income

On paper, the optimal long-term path for investors would be to maximize total return with zero taxable distributions, then take income as needed using tax-deferred capital gains. But targeting low-income strategies reduces the opportunity set and limits diversification. Investors should instead use tax-advantaged accounts for the most burdensome income-producing assets like bonds and real estate.

Investors should also avoid the highest-yielding securities on the market, such as high-dividend funds that ignore the risk of value traps or covered-call strategies. These tend to come with higher fees and taxes and lower total returns, which is not a winning strategy.

Tax-conscious income investors can make meaningful gains by seeking out qualified dividends and opting for long-term capital gains in taxable accounts. And bond investors keen for stable income may find solace in bond ladders. Understanding the trade-offs of different income strategies should help investors of all circumstances make better investing decisions.

This article previously appeared in the June 2023 issue of Morningstar ETFInvestor.

3 Growth ETFs Having a Great Year

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/0fa19b38-60f6-4a0f-9e06-9869d9c57d52.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZHTKX3QAYCHPXKWRA6SEOUGCK4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MNPB4CP64NCNLA3MTELE3ISLRY.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/0fa19b38-60f6-4a0f-9e06-9869d9c57d52.jpg)