An Investor’s Guide to the Biden Administration

A look at the tools the president can wield and the public policy he might pursue.

Any meaningful impact that the incoming Biden administration can have on the private sector will likely take some time.

We expect the first 12 to 18 months of Democrat Joe Biden’s term will be largely spent undoing the Republican Trump administration’s rules—with minimal impact on company valuations.

We think the biggest effect a Democrat-controlled Congress would have on investments is a likely increase in the corporate business tax rate. We also think Democrats will work to provide more stimulus and expand healthcare coverage, primarily within the Affordable Care Act framework. The narrow Democratic majority in the U.S. Senate will help Biden make government appointments faster. But without a larger majority in Congress, a lot of public policymaking will be left up to executive action.

Here’s a look at what levers Biden can pull to enact his agenda and why we think most executive actions won’t have major impacts on most companies’ valuations (with few exceptions).

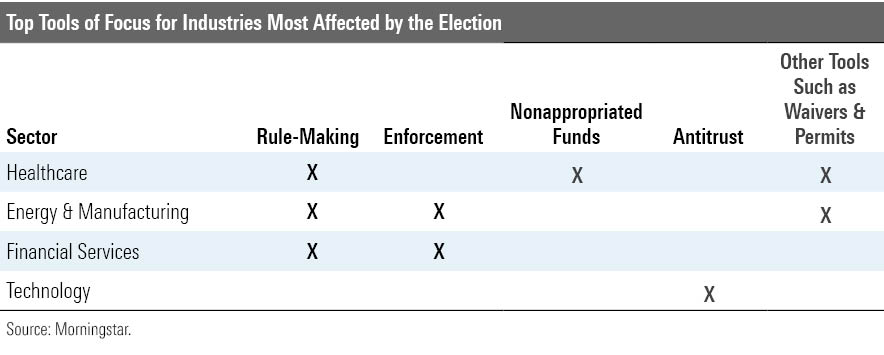

Tools the President Can Use to Shape Public Policy If Congress doesn't pass new legislation or update existing laws, the president still has a variety of ways to shape domestic public policy. (We'll cover trade and international relations in a later article.)

1) Rule-making and regulation. The president can set his policy agenda by directing agencies to issue new rules. While rule-making is the most powerful tool, it's also among the slowest. Most major rule-makings take 18 months to two years to complete. Plus, the results are often uncertain due to inevitable litigation. Agencies typically have broad authority, but Congress can be highly specific about what it wants and leave agencies with little room to set policy. The Biden administration will also freeze rules that haven't been finalized or aren't yet effective. To make an immediate impact, under the Biden administration, federal agencies will likely begin by issuing "sub-regulatory guidance." Such guidance doesn't carry force of law but can be issued quickly and can signal regulated communities about agency views and priorities. Democrats also can expedite the undoing of Trump-era rules via the Congressional Review Act, but they've been hesitant to take this approach in recent years. Here's how it works: For regulations finalized within 60 legislative days (which stretches back to late May), Congress can override the rule. This tool is not subject to a filibuster, so it can be done with 51 votes. But there's a catch: Taking this route bars agencies from making a substantially similar rule. Due to the risk of binding agencies, Democrats have historically been reluctant to use this tool, but they may use it in some cases this year.

2) Enforcement. Democratic administrations have historically been much more aggressive in enforcing regulations, particularly with regard to those protecting the environment. Ramping up enforcement can be much faster than making new rules, but it still takes time to develop enforcement targets. The threat of enforcement often leads companies to adjust behavior before agency action. Enforcement also allows agencies to reinterpret rules. In fact, a common complaint from regulated industries is that agencies engage in "regulation by enforcement." However, much enforcement of existing rules and laws in the U.S. is already completed through private lawsuits.

3) Using nonappropriated or flexible funds. The executive branch can't raise taxes on its own, but it can increase fees and then decide how to spend that money. Fee increases generally require rule-making, but how these dollars get spent is often reasonably unconstrained. Nonappropriated funds (meaning money that agencies raise but Congress does not directly control) are typically a small percentage of agency budgets, except for prudential regulators, which regulate banks. (The SEC relies on a user fee, but this fee is an appropriation for arcane reasons.)

4) Antitrust litigation. The Federal Trade Commission and Justice Department can try to break up certain companies if they can convince the judiciary that doing so would help to maintain a competitive marketplace. Over the past 40 years, antitrust litigation has largely focused on consumer welfare. However, we don't believe that the shift in administrations represents an inflection point for antitrust policy. The federal government and almost every state have already filed various antitrust cases against big tech firms.

5) Other tools: Many laws allow federal agencies to issue waivers, grant permits, provide grants with appropriated funds, or approve loans or loan guarantees. Taken in combination, the government can use these smaller, less-forceful tools to leverage larger changes that can affect businesses.

Now that we have covered the tools of government, we will turn to how a Biden administration might use them to shape public policy and the effect on key regulated companies in healthcare, energy and manufacturing, financial services, and technology sectors. In most cases, we don’t think these tools will materially change most companies’ prospects or our valuations.

Healthcare: Without Congressional Action, Biden's Administration Will Likely Expand Coverage at the Margins With Little Structural Change When it comes to healthcare, the ball is very much in Congress' court. Although Biden endorsed a public option while running for president, we think Congress will primarily try to expand coverage through the existing ACA framework by enhancing Medicaid to include people further from the poverty line in all states and increase the subsidy in the individual marketplaces to reduce the costs for lower-income households. Such an expansion could cost between $85 billion to $105 billion annually. Either approach would rely on the existing private insurance system, and we don't believe it would dramatically affect valuations for most firms we cover.

With or without Congress, we think the new administration will draft new rules on short-term health plans, raise nonappropriated funds to restore advertising and other support for federally run exchanges (although Congress would include new appropriations in any legislation), and use waivers to expand eligibility for coverage, such as in the Medicaid program. The redirection of funds and waivers could happen within 2021, while we expect the new rules to become effective in early 2022.

Most of these executive actions will simply undo steps the Trump administration took, and we do not expect them to change valuations for major healthcare players.

Rule-Making to Reduce Duration of Short-Term Healthcare Plans We expect that the administration will restore Obama-era rules for short-term health insurance plans, reducing the maximum period of coverage from 364 days to three months. It took the Trump administration until August 2018 to make these changes. Although we think the Biden administration will prioritize these changes, they likely wouldn't take effect until 2022. These plans covered around 160,000 people in 2016 according to a Department of Labor analysis. However, despite the increases in duration allowed for these short-term plans, they only covered 188,000 people by the end of 2019, according to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. This slight increase occurred because many states banned such plans in response to the change in rules or the required availability at the old limit of three months maximum. Therefore, we do not expect this to dramatically change the number of insured Americans, nor to affect individual exchange marketplaces.

Restoring Funding for Advertising and Other Exchange Supports Although it technically requires a new rule, the Biden administration can increase the fees insurers pay to offer insurance on the federal exchanges quite quickly and without notice and comment. By raising a modest sum of money (in the $100 million range), the administration can restore some advertising for these exchanges and perhaps some money for grants to navigators. Earned media from the president touting the exchanges during the next open enrollment period may be even more significant. In any case, these actions should help increase the number of insured people through the exchanges and could help reduce average costs if the ads influence healthier people to sign up but are unlikely to have a major impact on the insurers who offer coverage through the exchanges. Should Congress take up healthcare, it can provide even more funds for advertising.

Using Waivers to Expand Coverage The ACA and Medicaid statutes provide broad authority to the Secretary of Health and Human Services to approve waivers to states to either expand or contract eligibility. The Trump administration, for example, allowed states to tie Medicaid eligibility to work requirements in certain cases. In a reversal of the Trump administration policies limiting insurance coverage, we would expect the Biden administration to find ways to expand coverage through existing insurance channels, such as Medicaid. Also, while we think a dramatic expansion would be highly unlikely due to fiscal constraints, the ACA explicitly allows for waivers to use Federal funds for Medicaid and for the exchanges to establish a state-level single-payer health system. While activists may float this idea, we think that is very unlikely to happen, because a willing state would need the political capital and financial resources to find major additional funding for such a scheme. As states typically must balance their budgets, this would require raising taxes. Moreover, most states are in poor fiscal shape due to the pandemic. Nonetheless, the Biden administration will be amenable to states seeking waivers to expand Medicaid coverage to new categories of uninsured. Again, we do not expect such major changes in coverage that these waivers would affect our valuations, and we continue to believe that a universal single-payer system is not plausible in the foreseeable future.

Energy, Emissions, and Environmental Regulations: A Slow, Uncertain Return to Obama-Era Rules With a Sharper Shift on Permitting and Enforcement The Trump administration finalized hundreds of environmental rules that have affected energy companies over the past four years. It could take years for the Biden administration to reverse them and set a different course; however, many major rule shifts under the Trump administration have come too late to have a major effect. We continue to believe the kinds of extreme policy shifts that would make currently undervalued oil and gas stocks overpriced are not possible unless Congress changes current law. Automakers should be well-positioned to thrive, as the new fuel standards just recently went into effect and they have planned for a lower carbon-emission economy and therefore the likely abrupt reversal of these more-accommodating standards.

Rule-Making on Corporate Average Fuel Economy, Clean Power, and Greenhouse Gases As was the case for Trump's deregulatory push, we expect the Biden administration will need time to restore the Obama-era regulatory approach aimed at reducing greenhouse-gas emissions under current law. In the meantime, the private sector has largely embraced moving to a lower-carbon economy. For example, by grounding their economic analysis in cost and safety, the Trump administration was able to reduce fuel economy requirements in the Corporate Average Fuel Economy, or CAFE, standards. Changes to these standards—as with other rule-makings—generally take time. Although the Trump administration used a built-in review process to adjust the CAFE standards, the need for a new regulatory impact analysis meant the project took more than two years. The Biden administration will probably spend a similar amount of time preparing justification to adjust the average corporate fuel efficiency standards to 47 miles per gallon or higher, grounding their rationale in costs of carbon-related externalities. However, the Trump-era rules, which apply to car model years 2021-26, were only finalized in June 2020. The Biden administration would likely set rules starting in 2026 for the 2027 model year. For their part, automakers are already planning for a lower-emission world, have been operating under the Obama-era rules for some time, and know revised standards of restoring or expanding them are likely. In terms of fossil-fuel use, the new standards would lift fuel efficiency compared with our base case in the first few years, but by 2030 we would not expect a meaningful difference. Any reduction in short-run fossil-fuel consumption would be modest and unlikely to affect our midcycle commodity price estimates, fair value estimates, and moat ratings for energy stocks.

Similarly, EPA finalized new rules on methane emissions in August of this year for the oil and gas industry, rolling back Obama-era controls on methane, a major contributor to climate change. As with other complex rule-making, these rollbacks took more than two years to develop and finalize. While the government’s regulatory impact analysis suggests modest overall savings for the industry, in the range of $17 to $19 million annually, we do not believe reversing the rule will result in similar reductions in profits for regulated companies. To comply with the methane reductions, utilities will need to invest in their equipment, and these capital expenditures can drive earnings growth for regulated utilities. Large fossil-fuel companies with big natural gas portfolios have also been highly supportive of tighter regulations because they help position natural gas as cleaner alternative fuel.

Likewise, when the Trump administration replaced the 2015 Clean Power Plan with new, more-permissive rules allowing higher emissions largely from coal-fired power plants (an action they completed in June 2019), it did not result in us changing our fair value estimates, moat ratings, or moat trend ratings. Simply put, renewable energy and natural gas have been displacing the coal generation for years because it is cheaper. The Biden administration will stop defending the new, more lax standards in court, and ongoing litigation may result in courts vacating the new rules and restoring the 2015 Clean Power Plan without new rule-making.

Finally, we expect some additional regulation of chemicals, such as Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. These regulations could cost the industry as much as $40 billion, including $11 billion in cleanup. Regarding PFAS chemicals, Congress recently attached reporting requirements for PFAS for manufacturers and water systems. Using existing authority under the Clean Water Act, the EPA will likely codify a recommendation to keep PFAS to 70 parts per trillion over the next few years. Given the reporting requirements, bipartisan consensus that PFAS should be regulated, and the existing regulation at the state level, industry has been anticipating this regulatory change for some time, and we believe the market has overestimated the impact on DuPont and Corteva.

Enforcement and Permitting Changes Could Hurt Some Issuers Federal land accounts for roughly 10% of all current onshore drilling and extraction, and we expect the Biden administration to sharply limit or even cease issuing new permits and leases for drilling on federal land. Over the next two years, existing permits will expire, although we do not believe they will be revoked. While extractive industries can pivot to non-federal land, some companies with a lot of current operations on federal land could be hurt (such as EOG Resources). However, exposed companies have been working to mitigate the impact by increasing their permitting activity in 2019 and 2020, giving them a buffer of up to two years if the administration does cease issuing new permits, as we expect. Gulf of Mexico operators, like Murphy Oil Corporation, are also vulnerable, as the Department of the Interior also grants permits for offshore drilling. Similarly, EPA enforcement of environmental rules has been muted over the past four years. We expect a Biden administration to enforce rules more aggressively, which could modestly increase costs overall for industry, but it remains to be seen which particular companies find themselves targets of major fines. Also, it is worth keeping in mind that environmental laws are often enforced through private litigation, and the election will not change the course of those lawsuits.

Financial Services: We Expect Another Strong Push for Fiduciary Standards of Conduct The Securities and Exchange Commission and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau have broad authority to regulate financial services, enforce those regulations, and raise standards of conduct for financial advice or curb conflicts of interest. With a Democrat-controlled Senate, we expect the Biden administration will have an easier time getting nominees confirmed to run these agencies. The most significant rule-making will likely address practices that have been fast falling out of favor among financial advisors, asset managers, and brokers in any case.

The democratic agenda for the SEC is ambitious. It includes increasing enforcement of Regulation Best Interest, enhancing the standards of conduct in it, as well as a renewed focus on Registered Investment Advisors and particularly, dual-registrant advisers and broker/dealers. Democrats would also like the SEC to take a more skeptical view of exempt offerings and focus on capital flowing through publicly traded markets, and there is a strong push to add more ESG disclosure for issuers. With chairman Jay Clayton departing, the SEC will have four commissioners and one vacancy. With Biden’s appointment, there will be three democratic commissioners who can shape the commission’s agenda. However, we believe most firms, in responding to Regulation Best Interest and the fiduciary rule, have already largely mitigated their conflicts of interest. Moreover, unlike the 2016 rules package, a further expansion of Regulation Best Interest does not set up an unpredictable private right of action, so it does not include litigation risk.

The Labor Department has already proposed a revised fiduciary rule, and we expect the Biden administration to delay and expand that rule. However, given the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals ruling in 2018, there are limits to what the department can do outside of the plans subject to ERISA, such as 401(k) plans, which are already tightly regulated.

Turning to the CFPB, we expect Biden to replace Trump’s pick with a director of his own who will pursue stricter rules and enforcement. Even then, we don’t expect a major shift in policy at the bureau that would dramatically change valuations. For example, the CFPB may make a push on regulating overdraft fees, but these fees are not a major part of large bank profits, so we do not believe these kinds of actions will affect valuations. The stepped-up enforcement will result in more fines than we have seen in the past few years, but these will probably not be sufficient to affect valuations.

Technology Firms Are Squarely in Antitrust Crosshairs, and a Bipartisan Consensus on Privacy Creates Some Risk From New Legislation Unlike other sectors, tech firms such as Facebook and Google face threats from antitrust litigation in which the federal government has broad authority. However, we do not view Biden's election as an inflection point in this litigation. Indeed, both Facebook and Google face current antitrust suits launched by the states and the federal government. They also face risks, albeit with much higher uncertainty, from Congress taking up new privacy standards. Furthermore, we continue to believe that even aggressive enforcement of antitrust laws will likely not strip Facebook or Google of their network effects or other competitive advantages. Should regulators seek to break up Facebook or Google, we believe shareholders may benefit, as both companies are worth the sum of their parts and spin-offs would retain high values.

Congress Will Consider Establishing a New Agency With Broad Authority to Regulate Online Privacy In a 2019 report, the U.S. Government Accountability Office told a House committee that "Congress should consider developing comprehensive legislation on Internet privacy" that would bolster consumer protections and be flexible to the ever-changing nature of the Internet. Such legislation, the GAO said, could include delegating rule-making authority to an existing agency or creating a new one. The recommendation from the GAO, Congress's in-house think tank, clarifies that there's little that can be done to address Internet privacy under current law, so congressional action is required. Were this a strictly partisan issue, we might be waiting for some time for such action, but it's not. The top Republican on the Senate Committee with jurisdiction has proposed bills broadly aligned with Democratic priorities on individual privacy rights and transparency. Ultimately, we expect if legislation were to pass, it would likely reduce revenue opportunities for some tech companies, while strengthening their economic moats by making it more difficult for new entrants to comply with regulations or put together a business plan with a path to profitability. Because Congress has little in-house expertise on technology, lawmakers will have to rely on outside experts and those who they're trying to regulate to craft workable legislation. This means that any changes will be fairly accommodating to corporate interests. The recent violent riots and disruption to the certification of the 2020 election at the Capitol will have a minimal impact on the regulation of major social media firms, and do not change our assessment that bipartisan consensus is more likely for privacy concerns than for new antitrust tools or redefining firm liability for user-generated content.

While the Federal Government may Pursue Further Antitrust Litigation, Major Players Do Not Face Existential Threats Most existing antitrust tools aren't sufficient to upend the business models of big tech companies and Congress is unlikely to expand existing antitrust laws. As detailed in previous reports on Morningstar Direct, antitrust laws may be used to restrict mergers and acquisitions but demonstrating broad consumer harm from current technology monopolies will be challenging to impossible. We previously estimated that in the worst-case scenarios, fair value estimates could fall in the 10- to 15-percent range for Facebook and Alphabet, a far cry from wholesale restructuring of their businesses.

Specifically, regarding Facebook, which faces litigation from 47 states and the FTC, we expect that the courts will side with the plaintiffs by restricting future market acquisitions such as those for WhatsApp and Instagram. As detailed in a recent analyst's note, we do not expect the courts to force Facebook to spin these entities off, as it would be hard to prove that their control by Facebook hurts consumer welfare. If courts did so, we estimate shareholders would benefit in the short term, as our fair market valuation for Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp is $363 per share, higher than our current fair market estimate of $306 per share.

With Google, we are skeptical for similar reasons of a forced breakup, and we believe the sum of Google's parts is at least as valuable as the company. Google may have to pay fines to settle the case the DOJ and 35 states have brought alleging that Google's search results reduce competition as well practices that continue to lock in Google search as a default on various devices. Google also faces suits targeting its advertising business, although we are more skeptical of these given the declines in ad prices and increases in competition. Based on the consumer welfare standard that has guided jurisprudence on antitrust cases for four decades, we do not believe the plaintiffs will prevail in forcing a breakup, and we are maintaining our fair value estimate of $1,980.

Joshua Aguilar, Preston Caldwell, Eric Compton, Seth Goldstein, Richard Hilgert, David Meats, Travis Miller, Ali Moghrabi, Travis Miller, David Sekera, Julia Utterback, David Whiston, and Michael Wong contributed to this report.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c6d5b386-6df4-434b-bf56-ac0c9546e5aa.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GJMQNPFPOFHUHHT3UABTAMBTZM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/VUWQI723Q5E43P5QRTRHGLJ7TI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/XF7WENSYN5BFBFLPPFH7BJYUHE.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c6d5b386-6df4-434b-bf56-ac0c9546e5aa.jpg)