The (Limited) Case for Investing in Alternatives

Does Vanguard’s recent private-equity announcement bolster the argument for alts?

Vanguard's recent announcement that it is launching a private-equity strategy brings front and center (not for the first time) the question of whether (and to what degree) individuals should allocate some portion of their portfolio to alternatives. Granted, Vanguard is initially making the product available only to institutional clients, but given Vanguard's vast retail presence, not to mention CEO Tim Buckley's statement that its partnership with HarbourVest Partners "will present an incredible opportunity" for individuals investors, one suspects that it's only a matter of time.

The notion of “hedge funds for the masses” is hardly new. The boom in liquid alternative mutual funds after the 2008 financial crisis was supposed to provide individual investors with a tantalizing opportunity to access the same types of strategies typically reserved for institutions and the ultra-wealthy, all at a fraction of the cost and with increased transparency and liquidity. Has the reality matched the hype? Should investors look to take advantage of alternative asset classes, whether in liquid public or illiquid private investment structures?

What We Talk About When We Talk About Alternatives There's no single agreed-upon definition of what constitutes alternatives, but broadly speaking we can think of alternatives as strategies or asset classes that provide low correlations to the traditional portfolio building blocks of stocks and bonds, and thus serve to diversify a portfolio and improve its risk-adjusted performance (or its portfolio efficiency, in the lingo of Markowitzian Modern Portfolio Theory). A somewhat more expansive version of the definition incorporates illiquidity as a trait of alternatives, thus bringing private equity into the fold, despite its meaningful correlations with growth equity (as AQR's Cliff Asness recently argued, PE can be thought of as analogous to a leveraged small-cap growth portfolio). While some hedge fund strategies, such as merger-arbitrage, equity market-neutral, and managed-futures, have proved readily adaptable to liquid structures (minus excessive leverage), less-liquid strategies such as private equity and distressed debt do not work so well in open-end vehicles.

The Endowment Effect Alternatives have achieved their current reputation and mystique in large part because of the success of the Yale endowment under David Swensen, in what has come to be known as the endowment model. Beginning in the 1980s, Swensen eschewed the typical practice of investing heavily in bonds and stocks, turning instead to private equity, hedge funds, and real assets such as timberland. Other major university endowments adopted the model, and soon enough many pensions also turned copycat. According to the NACUBO-TIAA 2019 study of endowments, the dollar-weighted average allocation to alternatives across all endowments and foundations it surveys was nearly 40%, with another 12% in real assets.

It is understandable that people would look at the track record and tactics of the best institutional investors and say, "Hey, let’s adopt that model for individuals!" It’s also an oversimplification. There are several critical distinctions that make the endowment model less relevant for individuals, including:

1) Time horizon. Endowments have a perpetual time horizon, giving them an unusual capacity to withstand volatility and illiquidity, an advantage that you, dear reader, likely do not possess. If you are investing for retirement in your 401(k), then you do at least have a time horizon and objective comparable to a pension fund, but if your goals are nearer-term, the case is considerably weaker for incorporating alternatives.

2) Expertise. Hedge fund strategies (as well as their liquid-alternative counterparts) and private equity are more complex and less transparent than traditional investments. Larger endowments and pensions have extensive research groups equipped to do due diligence in these areas, while smaller outfits typically hire out the work to specialist consultants.

3) Access. Most private funds are available only to institutions or individuals who meet accredited investor definitions of income or total wealth (the SEC is currently reviewing some of the existing criteria for accredited investors). Moreover, even for those who meet the criteria, getting access to top-tier funds is often very much an insider's game, limited to investors with previous relationships with the managers.

Theory Versus Practice Putting aside (momentarily) the practical obstacles, the theoretical case for alternatives remains strong--adding noncorrelated assets with positive expected performance to a portfolio should, all things being equal, reduce drawdowns during market sell-offs and improve your overall risk-adjusted results, while some less-liquid assets offer the potential to outperform equities in the long term. Moreover, the anecdotal evidence of endowments and pensions taking up the cause for alternatives further bolsters the case.

But how strong is the case in practice? Here we run into some data-related challenges. Liquid alternatives are a relatively new innovation; of currently surviving liquid alts funds, only around 115 have 10-year records. Hedge fund and private-equity databases and indexes are subject to many well-documented biases, data-validity questions, and performance calculation debates. Still, we can only do the best with the data we have and make decisions based on those findings.

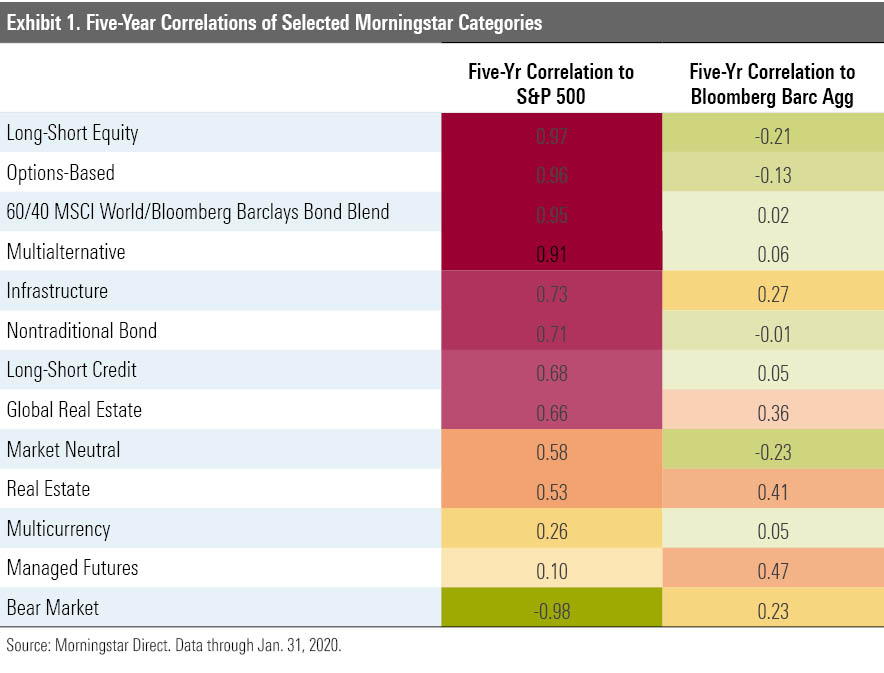

The story told by the available data is, at best, uninspiring. Let’s begin with correlations. Exhibit 1 shows five-year correlations to the S&P 500 and Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Bond indexes, based on monthly return for Morningstar alternative categories (too few alts funds have 10-year records to produce a robust cohort), plus a few others sometimes considered as alternatives, including nontraditional bond and several real-asset groups. Relative to the stock index, very few categories provided significant correlation benefits. Unsurprisingly, the stock-based long-short equity and options-based categories generate very high correlations with stocks; more surprising is the correspondence of multalternative funds, which are supposed to offer exposure to a range of alternative strategies.

Real estate funds did provide moderate diversification benefits, with a 0.53 correlation over the period, while the 0.58 correlation of market-neutral funds is disconcertingly elevated for a group of funds that are supposed to minimize market exposure (however, a subset of the category, including event-driven and merger-arbitrage funds, does have net long exposure). The only true diversifiers were managed-futures, multicurrency, and bear-market funds, the latter of which bet directly against the market through short positions. The correlations to fixed-income are far lower, but the risk that most investors likely need to diversify away from is equity risk.

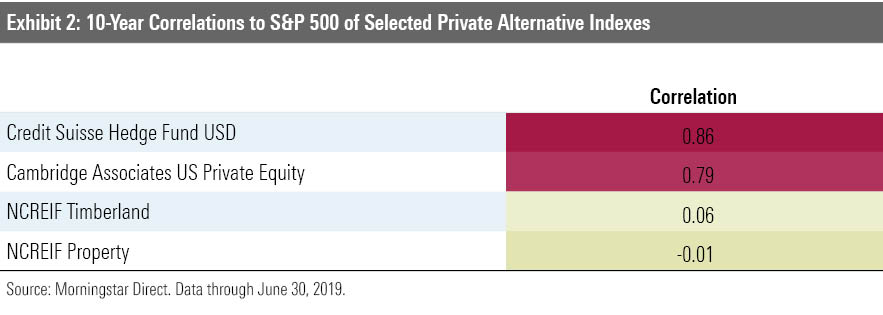

I also looked at the correlations of several private market indexes. Because several of these data providers report performance only quarterly, I used correlation based on quarterly returns through June 30, 2019, but going back 10 years. There was a similar divide here. The two real asset indexes, which are based on direct investments in timberland and property, exhibit very low correlations (however, smoothing characteristics of those indexes may lead to artificially suppressed correlations); at the same time, the hedge fund and private-equity indexes show relatively high correspondences with stocks.

Averages can mask significant variation, of course. These figures don’t mean you cannot get the desired diversification benefits from an alternative fund, but you’ll have to put some work into it. There can be significant dispersion within categories. For example, five-year correlations in the market-neutral category run from 0.87 at the top end to negative 0.81 at the low end, while in the multialternative category, despite high average correlations, one fourth of the funds with five-year track records have correlations of less than 0.30.

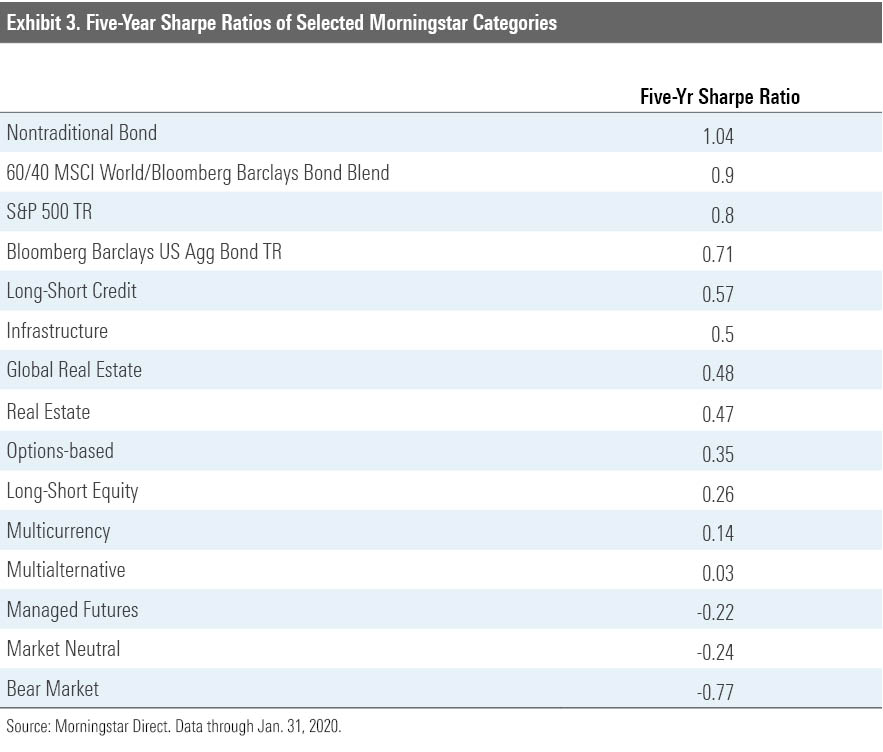

Correlation is only part of the story. Whether offering greater or lesser degrees of correlation, have alternative strategies been additive from a risk-adjusted performance perspective? One way to check this is by eyeballing funds’ Sharpe ratios. Again, the results aren’t particularly persuasive (see Exhibit 3). For comparison purposes, a 60/40 global blended benchmark earned a Sharpe ratio of 0.90 over the five-year period. The only category to beat that benchmark’s Sharpe (admittedly, a strong period for stocks and core bonds) was the nontraditional bond category. Several of the alternative categories produced negligible or even negative Sharpe ratios, disappointingly including lower-correlation areas such as managed-futures and market-neutral.

The private alternative indexes, again using 10-year quarterly returns, generated more attractive performance results. The blended index had a 0.98 Sharpe ratio for the period (slightly better than its five-year result), which was nearly matched by the Credit Suisse Hedge Fund Index, matched by the timberland index, and surpassed by the property and private equity indexes. I take those results with a dash of salt, as the volatility levels (the denominator in the Sharpe formula) are likely suppressed because of smoothing effects (a result of the lagged reporting of values with such investments), inflating the Sharpe as a result. Still, it does seem likely that the private equity and direct real estate, in particular, have provided strong performance and diversification benefits during the past decade.

The generally disappointing results observed in these metrics are reinforced by a study conducted in 2018 by my colleagues Jason Kephart and Maciej Kowara, which used an optimizer to analyze the effects of adding alternatives to a hypothetical 60/40 portfolio. They found that “most liquid alternatives would have failed to improve the starting portfolio” over the three- and five-year periods covered.

Further external confirmation comes by way of CEM Benchmarking's "Hedge Fund Reality Check" study from May 2018. Rather than using hedge funds' own self-reported benchmarks, CEM created customized, investable blended global balanced benchmarks that had high correlations to hedge fund performance, then looked at the excess returns produced by the hedge funds over a 17-year period. On average, the researchers found a net negative value-add of 1.27% annualized relative to those benchmarks; 36% of funds did exceed their benchmarks, but the majority of those did so by only 1% to 3%. The overall result indicates that most hedge funds perform no better than straightforward passive balanced portfolios.

Conclusions and Caveats The empirical case for including alternatives as a diversifier to equity risk and as a return enhancer is less persuasive than the theoretical case. Private funds may offer better results, but access to them is limited, and even then the benefits are often uncertain. Private equity likely offers the best long-term potential, but access is limited and lockup periods are long (at least until more retail-friendly options emerge from Vanguard or other innovators). Real assets offer some diversification potential, but their value may lie more in their value as an inflation hedge, an area I have not pursued in this article but plan to in the future.

One big caveat lies behind all of the above. These results are based on historical (and often limited) data, and the future could look very different. In particular, it is worth noting that the past decade has seen a virtually uninterrupted equity bull market, along with a strong market propelled by declining interest rates, featuring unusually low and stable volatility. Alternative strategies tend to fare better during periods of elevated volatility and market stress, and many are further boosted by higher interest rates. Whether or how long the past decade’s market conditions can continue is anyone’s guess. One lingering concern, however, is the heightened correlations noted above and in the Kephart/Kowara study, raising the question of whether they will offer protection in a drawdown scenario. Many reasons have been suggested for the rise in correlations; one could be that managers have increased beta exposure in light of the strong equity markets and could easily shift back, given their wide mandates. Other explanations point to structural factors that might make it more difficult to disentangle certain hedge fund strategies from the broader markets.

This is not to say that individual investors should never make allocations to alternatives. Given the greater complexities, risks, fees, and potential for adverse selection with alternatives, the bar should be much higher for deciding to invest. Unlike the 30%-plus allocations to alternatives seen with many endowments, or the 15% to 20% allocations typical of pension funds, individuals would be better off restricting allocations to the 3% to 10% range--enough to have some impact on the portfolio but not so high as to potentially imperil the portfolio. Selecting a range of strategy types, or a multistrategy fund, will help mitigate the risk of idiosyncratic events. Focusing on funds that earn Morningstar Analyst Ratings of Bronze or better and which offer low correlations to equities or fixed income (depending on which risk you wish to diversify away from) can also help lead to better outcomes. If you meet accredited investor criteria and have access to private products through a wealth advisor, the case for alternatives may be yet stronger.

If you are investing through your 401(k), you likely won’t find stand-alone alternatives as an option, as their fees and idiosyncrasies make them unpalatable to most plan sponsors. To my mind, allocation or target-date funds that incorporate alternatives would be the most sensible route for individual investors; unfortunately, there aren’t that many options that do so. Vanguard Managed Payout VPGDX allocates about 12% of assets to Vanguard Alternative Strategies VASFX Other firms have incorporated direct real estate into CIT versions of their target-date products, while Vantagepoint announced last year that it would gradually incorporate private equity into its CIT target-date funds. Some large U.S. firms have taken a more innovative tack with custom retirement offerings, incorporating hedge funds and private equity into such products, leveraging work they have already done on the defined-benefit side of their investment committees. Such products can make sense because the long time horizon for retirement investing aligns with the less-liquid nature of many alternatives, and investors in defined-contribution plans have shown little tendency to trade out of investments like target-date funds, even during the 2008 bear market.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/2e13370a-bbfe-4142-bc61-d08beec5fd8c.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HTLB322SBJCLTLWYSDCTESUQZI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/TAIQTNFTKRDL7JUP4N4CX7SDKI.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/2e13370a-bbfe-4142-bc61-d08beec5fd8c.jpg)