The End of Favorable Tax Treatment for Inherited IRAs?

Congress’ next “pay-for” is not as significant as it seems at first glance.

As part of a set of retirement provisions in the Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement Act of 2019, or SECURE Act, Congress would make it harder for heirs who inherit a tax-deferred retirement account (like a 401(k) or an IRA) to shelter the money from Uncle Sam. The set of provisions enjoys wide, bipartisan support, so it's likely to pass sooner rather than later. These rule changes may at first seem like a big change, but taking a wider view, they probably won't have much of an impact.

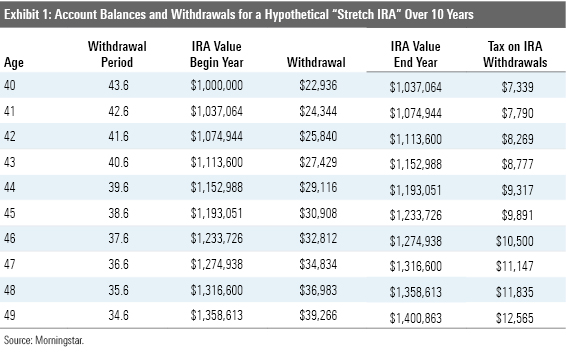

Congress is making this change to how heirs must take distributions (and ultimately pay taxes) on Traditional IRAs and 401(k)s because lawmakers needed to find revenue to offset the costs of other provisions in the SECURE Act. Right now, most heirs who inherit a Traditional IRA or other defined contribution account get a huge tax break because they only need to take distributions based on their life expectancy. For example, if a 40-year old inherits an IRA, his required minimum distribution is just 2.29% at the end of the year, based on his 43.6-year life expectancy. Obviously, this gives him the ability to shield his inherited IRA from taxes for a long time.

To raise about $1.5 billion a year over the next 10 years, Congress is proposing to require people, other than spouses or disabled children, to withdraw their inherited IRA balance within 10 years. People could defer the withdrawals for 10 years or take them incrementally, which might help keep them in a lower tax bracket.

The first clue that, in the grand scheme of things, this is not a huge deal should come from that revenue number--$1.5 billion a year, or $15 billion over the next 10. IRAs and 401(k)s have around $16 trillion in assets. Changing the stretch provisions amounts to a tiny tax increase on the total base of assets. Further, it pales in comparison to the $1.26 trillion the government expects to give up in taxes over the next 10 years by deferring taxes on retirement savings. In short, it won't affect most people much if it affects them at all. After all, few inherit large sums of money in IRAs, in part because of required minimum distributions for the original account holder.

Still, that’s probably small comfort if you stood to inherit an IRA at a reasonably young age. (The provision would go into effect in 2020, and current stretch-IRA holders would be grandfathered into the old rules. Of course, since no one knows if they would benefit from these provisions in advance, there’s no natural constituency to protect the stretch provisions.)

In any case, the tax hit looks bad from these changes, at least at first glance for a would-be heir.

To take a stylized example, let’s consider a 40-year old who inherits a $1 million IRA. Under the new rules, he’d have to withdraw all the money over 10 years. Assuming he earns 6% in nominal returns, he is stuck taking a bit more than $135,000 out annually, and he will ultimately pay around $435,000 in taxes, assuming he is in the 32% marginal tax bracket. (He could also take all the money out in year 10, but that could substantially raise his tax burden as it triggered higher marginal rates, leaving him with more than $660,000 in taxes due in year 10.)

In contrast, under the old rules, after 10 years, he’d have $1.4 million in the account, having taken out less than he earned over the same time period, with a total tax payment of around $97,000 on just $304,000 of withdrawals. See Exhibit 1 below for an illustration of this scenario under the current rules.

So, at first glance, it looks bad. But it’s not quite as terrible as it looks at first glance. Under the proposed changes, the 40-year-old heir is still generating an aftertax cash flow of $97,000. Even assuming an aftertax return of 4.5%, he could have an account balance of $1.19 million by simply reinvesting the money. Just because the government says you must take a required distribution does not mean you cannot reinvest that money.

Further, marginal tax rates may well be higher in the future than they are today. Sure, under the current rules heirs to IRAs can keep the money for longer. But that’s not all that great if they end up taking it out later when marginal rates are higher. No one knows for sure what tax rates will look like in the future, but the long-term imbalance between expenditures and revenue needs to be solved eventually, and raising taxes will probably be part of that solution.

While some have argued that this change sets a bad precedent, it is at least squarely in line with the bargain people know they are getting when they take advantage of tax breaks to save for retirement. You get a tax break now and while the money compounds, but you pay tax in retirement, or at least after you die! There may be some strategies that the end of the stretch IRA might make more appealing, such as Roth conversions, but ultimately, as long as heirs remember they can invest their distributions from a stretch IRA, these changes are not nearly as large as they first appear.

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this article applied the incorrect withdrawal methodology for stretch IRAs, slightly inflating the tax benefits.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c6d5b386-6df4-434b-bf56-ac0c9546e5aa.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-24-2024/t_a8760b3ac02f4548998bbc4870d54393_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/U772OYJK4ZEKTPVEYHRTV4WRVM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c6d5b386-6df4-434b-bf56-ac0c9546e5aa.jpg)