An Equity Squirrel

Discovers Bonds Fixed income is where most investments reside.

The Spotlight of this issue is about fixed income. I spent my career following equities, so I am going to look at fixed income from an equity point of view. Stock managers may think of themselves as fighter pilots, heroic risk-takers laughing in the face of danger, and bond managers as boring airline pilots, glorified bus drivers. That metaphor is colorful but wrong. Fixed income is where the bulk of investments resides.

I traveled to Argentina in 1997 with my friends Nissim and Deena. After a splendid trip, it was time to take taxis to the Buenos Aires airport and head home. Nissim, a shrewd New Yorker, explained how he was going to negotiate a fixed price for the cab, while I decided to stupidly pay the meter fare. When we arrived, Nissim proudly announced he had done the trip for 40 pesos. I did not tell him that our meter read 36 pesos.

But the interesting part was that at that time, Argentina had pegged the peso 1:1 to the U.S. dollar. I thought that this cabbie would be thrilled to be paid in U.S. dollars. When I offered dollars to him, he said that he would take them but that he would much rather have pesos, which I gave him. The peso peg ended in 2002, and today the Argentine peso is worth only four cents U.S.

100-Year Paper So, currency prices dominate government-bond trading. Despite the long-term collapse of the Argentine peso, Argentina sold $2.75 billion worth of bonds in June 2017 maturing in 2117. No typo. It sold 100-year bonds priced to yield 7.9% rated B, and the offering was oversubscribed three to one. The bond was denominated in dollars, a good thing for the buyers, because in the 12 months since the offering, the Argentine peso has dropped from 16 pesos to the dollar to 25. As the peso sinks, the cost of servicing this debt rises dramatically, suggesting that there is a risk of default. As one investor told Reuters, "I'm not sure we can find a 20-year period where Argentina has not defaulted."

Others have sold 100-year paper, including Mexico, Ireland, and the troubled Brazilian national oil company Petrobras PBR. One question I can’t answer is why the United States has not sold a 100-year bond. We have $20 trillion in national debt, increasing every year, at very short duration. It is very likely we could sell $1 trillion in 100- year bonds at 3.5%, which is a cheap interest rate historically. There is a reasonable chance that a future Treasury secretary will be refinancing 2% paper at 6% and cursing her predecessor who didn’t lengthen duration when he had the chance.

Bavarian Sunshine A few years after Buenos Aires, we went to Munich to visit the Deutsches Museum. I am a trustee of the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, a wondrous place to spend a day. It was modeled on the Deutsches Museum, so I was eager to visit the original, which is also a great museum. The Museum of Science and Industry is designed for a middle school and high school demographic, while the Deutsches Museum is aimed at an adult audience.

The first thing that catches your eye when you approach the Munich museum is the line of people waiting outdoors to get in. The museum has a small, oval ticket office with room for two ticket clerks. That is way too few, so there is a long line outside in the Bavarian sunshine.

Unfortunately, Bavaria doesn’t do sunshine very well, so actually people are huddled in a long queue under their umbrellas, raising the question, “If you are exemplifying the greatest German technology, why haven’t you figured out a way to sell me a ticket without my having to stand in the rain?”

When I got back to Chicago, I was given a report, “The Deutsches Museum of Munich,” a typed manuscript written by Waldemar Kaempffert[1] and addressed to Mr. Julius Rosenwald, president of the Museum of Science and Industry. It was dated Feb. 1, 1929, when the Chicago museum was in its planning stage. In this report, Kaempffert noted “an inadequate vestibule for the reception of hundreds who seek refuge in the Deutsches Museum from the rain.”

The Museum Indicator The great Deutsches Museum is a monument to German science that was the best in the world in 1908. How could the Germans not find the money to fix the ticket office in 90 years? My theory is that Germany has operated as a welfare state, and in a welfare state, entitlement programs such as healthcare and pensions, plus interest on its national debt, eat up all the money. Museums don't have the political constituency to make capital expenditures, so improvements don't get made.

American museums, such as the Museum of Science and Industry, are supported by private philanthropy, which has been a reliable funding source. The museum has built indoor parking and state-of-the-art ticket selling.

A tip to investors, whether you’re investing in bonds or stocks: Watch out for grandiose projects. When Germany decided to build the Deutsches Museum, Germany was the leading country in the world in technology, industry, political stability, and military power. In 1908, the museum project was a top indicator. Twenty years later, Germany was defeated and bankrupt, and the 20 years after that (1929–1949) were disasters for Germany and all of Europe.

When Rosenwald decided to build the Museum of Science and Industry, U.S. industry was supreme, and his company, Sears Roebuck, ruled retail. The decision to build was made in 1929. The museum was opened in 1933, in the depths of the Great Depression.

Sears signaled another top when it built the Sears Tower (now, called the Willis Tower). Construction on the grandiose 110-story building began in 1970—the year that tiny Walmart WMT had its IPO.

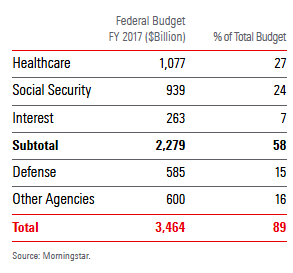

Looking forward, our federal budget is dominated by healthcare and Social Security. These expenditures will grow every year. A third giant expenditure will be interest on the national debt. The current debt is $20 trillion, and in 10 years, it will be $30 trillion. At 3% interest, the annual expenditure on $30 trillion debt is $1 trillion, which means that interest will be almost as big as healthcare and Social Security.

This means that all other government programs will be continually squeezed, as the big three devour all the money. The chance of funding any important new program is very unlikely.

[1] Waldemar Kaempffert was the famous science editor for The New York Times from 1927 to 1956. The Museum of Science and Industry hired him to be its director, but he had a fight with the board and went back to New York.

This article originally appeared in the August/September 2018 issue of Morningstar magazine. To learn more about Morningstar magazine, please visit our corporate website.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)