Should You Diversify Your Bond Exposure?

The 'right' bond exposure--from a credit and duration standpoint--depends on your circumstances and portfolio.

Q: I'm thinking of retiring in about two or three years. Most of my bond exposure is currently in short-term bonds. Is it a bad idea to diversify my fixed income so I get a bit more of a return? Right now my return in short-term bonds is probably not even keeping up with inflation. But diversifying into a rising interest rate worries me.

A: The "right" bond exposure is really the right bond exposure for your portfolio. That means not only the size of the overall allocation to bonds in your portfolio, but also the diversification within that bond allocation. The first step involves determining how much risk you're taking in your portfolio.

"Fixed income should bring diversification and downside protection, and should allow for other risk-taking," said Gibson Smith, former chief investment officer of fixed income and portfolio manager at Janus. "In my experience, too often investors chase yield in their fixed-income allocation ending up with highly correlated risks in their portfolios (think credit and equity)."

Finding the Right Overall Allocation There are several rules of thumb regarding the ideal fixed-income allocation based on the investor's age or time horizon, but many investors don't invest according to these rules-of-thumb allocations, which are often based on risk capacity rather than risk tolerance. (Note that these are different things, and they can be out of sync with each other.) Certainly if you are a younger investor with four decades until retirement, you have a large capacity for risk--you have plenty of time to ride out the market volatility that comes along with equities' higher long-term returns. An equity allocation close to 100% could make sense in your case. But if you cringe every time the market drops a few percentage points, your risk tolerance may not be in line with that risk capacity.

On the other side of the coin, if you are retiring in a few years, you have an interest in conserving the money in your portfolio. You don't have as much time to weather equity market downturns before you have to start living off the money in your portfolio. It makes sense, then, that your risk capacity is lower, and your overall exposure to bonds is higher. Of course, there are many circumstances in which those nearing or in retirement might be more aggressive with their investment allocation than their age dictates; perhaps they have other income sources and they plan to leave an inheritance to their heirs. But even if you have a high risk tolerance going into retirement, right-sizing your allocation to less-risky investments will help protect your retirement nest egg from getting wiped out in an equity market sell-off when you need that money to pay the bills.

The Morningstar Lifetime Allocation Indexes are a good example of a benchmark based on risk capacity. Further, there are three separate index tracks based on risk tolerance of the investor. For investors with more than 40 years to retirement (the 2060 vintage), the aggressive allocation starts out at 3% bonds (and more than 94% equity); the moderate allocation devotes about 7% to bonds; and the conservative allocation starts out with 17%.

By the time an investor is approaching and in retirement, 24% of the aggressive track is devoted to bonds, 33% for the moderate track, and 40% for the conservative.

Diversification Among Different Types of Bonds When determining what types of bonds you want in your portfolio, one important consideration is what role bonds play in your portfolio.

"I've always been a believer that higher risk taking should be balanced with more fixed income, especially Treasuries," said Smith.

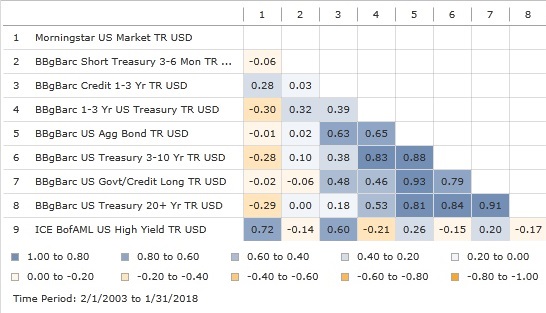

Take a look at this correlation matrix. (I used a 15-year period in an attempt to get a fuller market-cycle picture.) As you can see by the correlation to equities, U.S. Treasuries, which take on no credit risk, will give you the lowest correlation to equities. When equities sell off, high-quality bonds are the ballast in your portfolio.

- source: Morningstar Direct

The Barclays U.S. Aggregate Index, seen as a flagship benchmark for the investment-grade bond universe, has a higher correlation to equities than Treasuries of similar intermediate-term maturity (3-10 years); however, that the index has a higher allocation to Treasuries than most investment-grade bond funds. (In other words, many funds in the intermediate-term bond category will have an even higher correlation to equities than the Agg.)

So while a higher exposure to credit risk will give you more return over the long term, it isn't doing as much to offset equity risk. For instance, take a look at the high-yield bond index's 0.72 correlation with the US Market Index over 15 years.

The other issue is that of bond maturity. Going a little further out on the yield curve will give you more yield, but it also exposes you to more interest-rate risk. Smith says short- and long-term bonds "serve difference sources of risk and different outcomes."

One very practical concern is the one the reader alluded to in the original question: short-term bonds might not keep pace with inflation. This is a big reason one would want to diversify into bonds of longer maturity, even with rate hikes on the way. And in fact, it's not always obvious or predictable how bonds of longer maturity will act during a rate hike.

Of course, you want to understand what interest-rate risk you have in your portfolio, particularly as it relates to money that's intended to be used in the short term. But for assets in your portfolio that you won't need to tap for a decade or more, an intermediate-term bond allocation makes sense. Sure, you might see some losses during that time period, just like with equities. To really benefit from longer-term bond strategies, you have to be willing to hold through some volatility.

For examples of short- and intermediate-term bond allocations for aggressive, moderate, and conservative investors, as well as some fixed-income funds we recommend, see director of personal finance Christine Benz's Bucket portfolios, which are modeled after Morningstar's Lifetime Allocation Indexes. The basic premise of the Bucket concept is that assets needed to fund near-term living expenses ought to remain in cash and short-term vehicles. Assets that won't be needed for several years or more, meanwhile, can be parked in a diversified pool of long-term holdings, with the cash buffer providing the peace of mind to ride out periodic downturns in the longer-term portfolio.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/3a6abec7-a233-42a7-bcb0-b2efd54d751d.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/3a6abec7-a233-42a7-bcb0-b2efd54d751d.jpg)