How to Use Active Share to Evaluate ETFs

Not all ETFs are equally passive.

Exchange-traded funds rose to popularity on the shoulders of passive giants. Low-cost index funds pioneered by the likes of Vanguard, State Street, and iShares propelled ETFs into the mainstream, collecting trillions along the way. In the 30 years since the first ETF came to market (SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust SPY), ETFs have gathered almost $7 trillion in assets. The trend continued in 2022, with ETFs taking in almost $600 billion in net flows, far outpacing the $850 billion that flowed out of open-end mutual funds.

Passive investing and ETF investing have become synonymous because of the quick ascension of index ETFs like SPY. However, it is a misnomer to always equate the two. While the majority of ETFs are designed to replicate market indexes, those indexes are not as passive as they appear. Even the most basic indexes, such as the S&P 500, contain investment rules to control for risk and promote investibility. The index does well to include the 500 largest public companies in the United States, but it’s not perfect. It employs market-cap, liquidity, and profitability screens that push the index past the 500th largest publicly traded company. Practices like these are common across the ETF universe, and varying approaches by different indexes and funds contribute to small but notable differences between them.

Introduction to Active Share

Portfolio managers, index providers, and fund administrators make decisions every day that affect funds’ overall returns. Sometimes they’re routine, like managing daily cash flows and periodic rebalances. And sometimes they’re have more of an impact, like changing an index’s methodology or, for active managers, selecting stocks outright. Active share is a data point that captures the influence of these portfolio management decisions. It measures the portion of a portfolio’s equity assets that are invested in a way that diverges from a benchmark.

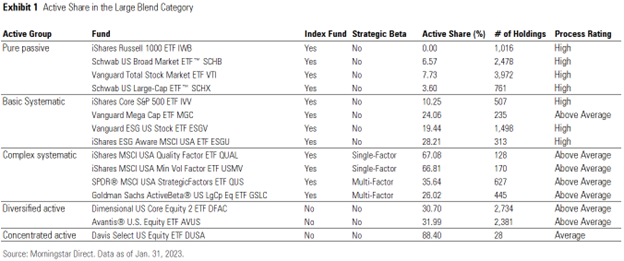

Active share may fall between 0% and 100% for a given fund. A portfolio precisely replicating the index has 0% active share, while a portfolio full of nonbenchmark holdings has 100% active share. The closer to 100% active share falls, the greater stock-picking risk, or active risk, an investor assumes relative to the benchmark. Exhibit 1 illustrates the differences in active share within the large-blend Morningstar Category.

For this analysis, I grouped 15 analyst-rated ETFs by the level of active risk assumed by their investment approach. The active groups are not an official Morningstar designation, simply my interpretation of each strategy’s focus. Active share is benchmarked to iShares Russell 1000 ETF IWB, an ETF proxy for the U.S. large-blend Morningstar Category index.

Spectrum of Active Share

Funds grouped as pure passive represent broad-market index ETFs that use minimal screens to ensure investibility and liquidity of each holding.

Basic systematic strategies consider more than just investibility or liquidity in their index’s construction, but not much more. ETFs tracking the S&P 500 fall into this group because that index uses a profitability screen that tilts the fund toward more-profitable names than ETFs in the pure passive group. Environmental, social, and governance focused funds that use simple screens on the broad market to filter out less-savory ESG names from the portfolio can also fall in this group. The level of active risk imposed by different ESG selection processes can vary, but for the purpose of this exercise they are grouped as basic systematic.

The complex systematic group encompasses single- and multifactor strategic-beta strategies, which focus on one or multiple factors their managers expect to provide an edge. Multifactor strategies spread their bets across factors, keeping diversification up and active share down relative to single-factor peers that concentrate their bets in a single factor. This causes single-factor portfolios to look starkly different from their category indexes, elevating active share.

These diversified active strategies do not follow an index but still systematically pick and weight stocks. Dimensional Fund Advisors and Avantis are among the leaders in this space, with robust academic research underpinning their strategies. Unlike concentrated active strategies, they tend to remain well-diversified across most of the opportunity set, which helps moderate active share. These funds are a good way to access the research expertise of each provider for a low fee.

Concentrated active strategies also allow investors to access the research expertise of each provider, but performance is much more dependent on the fund manager’s discretionary stock picks. The only analyst rated concentrated active ETF in the large-blend category is Davis Select U.S. Equity ETF DUSA. Its concentrated portfolio of just 28 stocks differs substantially from the Russell 1000 Index, which results in a very high active share of 89%.

How We Evaluate Active Share

Active share is a tool used by Morningstar analysts that can be a serviceable proxy for the level of active risk taken by a strategy. We typically prefer strategies with lower active share because history tells us passive funds usually beat active funds over extended time periods in efficient categories like U.S. large blend. Process Pillar ratings of High are usually reserved for pure passive or basic systematic strategies within our ratings framework.

However, research from the likes of Eugene Fama and Kenneth French show that intentional exposure to certain risk factors can provide a long-term edge if applied to a well-diversified portfolio.¹ Fama’s star pupil at the University of Chicago, David Booth, cofounded DFA in 1981 on those principles. Both Fama and French act as consultants to the firm and serve on the board of directors.

We recognize that a superior investment process grounded on solid principles can generate risk-adjusted alpha. That is the basis for the Process Pillar of Morningstar Analyst Ratings. Therefore, sensibly taking active risk is OK, but long-term category-relative performance is muddied by an excessive allocation to uncompensated risks, like stock-specific risks or sector concentration. A well-diversified portfolio avoids unnecessarily choppy performance that can deviate substantially from its benchmark.

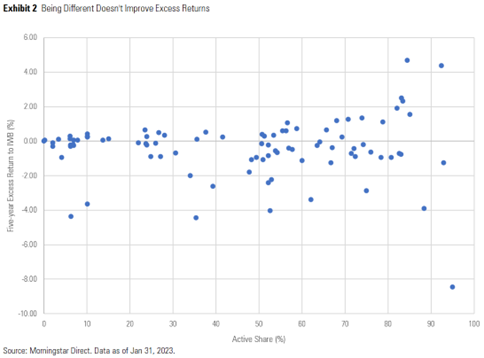

Exhibit 2 shows no strong relationship between active share and fiv--year excess returns among surviving ETFs in the large blend category. Each ETF’s excess return and active share were calculated using IWB as its benchmark. Venturing further along the active share spectrum can lead to better performance than the benchmark, but not always. The dispersion of excess returns increases most significantly once active share passes 50%. This demonstrates the relative gamble taken by those who invest in funds with significant active share. Previous Morningstar research also supports the notion that excess active share may go uncompensated.

How You Can Evaluate Active Share

Calculating active share can be difficult without advanced portfolio analysis tools like those offered by Morningstar Direct. But most investors don’t need to do forensic research to glean active risk. Since active share measures the differences in holdings between a portfolio and a benchmark, observing portfolio metrics on morningstar.com can get you in the ballpark.

First check the Morningstar Style Box for a simple style and size comparison. Then look at the number of equity holdings and percent of assets in the top 10 holdings to estimate portfolio concentration. Next, compare sector allocations and factor exposures to the category average. Finally, quickly scan other metrics on the page to see whether there are any major differences from the category average.

A concentrated portfolio that differs substantially from the category average will pose the greatest active risk to investors. Well-diversified portfolios that resemble the category’s opportunity set are your best bet to achieve predictable performance patterns.

Active share is not the only tool in the chest, but it’s a useful signal for alerting investors to unseen risk. Deviating from the norm is OK—that’s how a fund generates alpha. But straying too far can add stock-specific risks and lead to unpredictable return patterns that may harm investors. Investors need to be conscious of risks posed by ETFs across the active share spectrum—active and passive alike.

¹Fama, E.F., & French, K.R. 1993. “Common Risk Factors in Stock and Bond Returns.” J. Financial Econ., Vol. 33, No. 1, P. 3. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0304405X93900235

The author or authors own shares in one or more securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/5db00d6b-9c2f-4da7-8f94-da4290cf3b4a.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/24UPFK5OBNANLM2B55TIWIK2S4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-18-2024/t_34ccafe52c7c46979f1073e515ef92d4_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/5db00d6b-9c2f-4da7-8f94-da4290cf3b4a.jpg)