The Small Advantage for Active Fund Investors

Today’s shareholders benefit from changing investment habits

The Gold Rush

Once upon a time, sophisticated financial advisors and do-it-yourself investors sought out obscure equity funds. Established funds, it was thought, had exceeded their expiration dates, like sour milk or child actors. The smart money preferred undiscovered funds. Not only could such funds’ portfolio managers freely invest in their best ideas, but they also would not face fame’s distractions.

Researchers scoured the industry, seeking candidates. Morningstar led the effort, as it had the largest group of mutual fund analysts. But other organizations also undertook the challenge, as did reporters at several monthly magazines, and even enterprising financial advisors. Everybody wished to plant the first stake.

The gold rush has largely vanished. While Morningstar still periodically evaluates younger funds, it rarely publishes articles on the topic. (When it does, the readership is modest.) Most of those magazines have since folded. And few current financial advisors pride themselves on their ability to find overlooked portfolio managers.

A Random Walk

As Thomas Kuhn famously wrote, there has been a paradigm shift. (Perhaps not “famously” to the mainstream, but for those of us who were graduate students during the 1980s, Professor Kuhn could not be missed.) Investors now evaluate funds very differently than did their predecessors. Back in the day, they credited or blamed the hired help. If a once-successful fund struggled, that was because it was overwhelmed with incoming assets, or its research team had defected, or its manager had become undisciplined. Somewhere, somehow, there was a reason.

No longer. Guided by the random walk theory, veteran investors now tend to regard fund performances as accidental. Funds hold a basket of stocks; that basket will perform according to the prevailing investment trends; and then things will change. Might as well predict next January’s weather as attempt to forecast which actively run funds will remain on top.

This mindset has much to recommend it. Regrettably, from the view of a former fund analyst, it better describes reality than does the assumption that portfolio managers control their own destinies. By and large, funds are buffeted (no pun intended) by investment fashion. Consequently, as Jack Bogle asserted, the two likeliest explanations for fund performances are 1) expense ratios and 2) luck.

Considering Fund Size

The two likeliest causes are not necessarily the only ones, however. Although the previous generation was too quick to spot patterns in the tea leaves, it perhaps was correct in paying attention to fund size. True, a 2018 study disputed whether size is related to returns, but an earlier article found a statistically significant link, as has an upcoming paper (as yet unpublished, but mentioned in one of my columns) from Morningstar staffers. The research’s judgment is a tentative yes.

That hypothesis is supported by the anecdotal evidence. Managers of small-company stocks funds often mention the difficulty of putting new cash to work. (Understandably, they rarely mention those problems on the record, but they do confess to them on background.) Also, the highest-performing hedge fund of them all, Renaissance Medallion, routinely shrinks its asset base by disbursing its profits. Obviously, Renaissance founder Jim Simons thinks that fund size matters.

Small-Value Funds

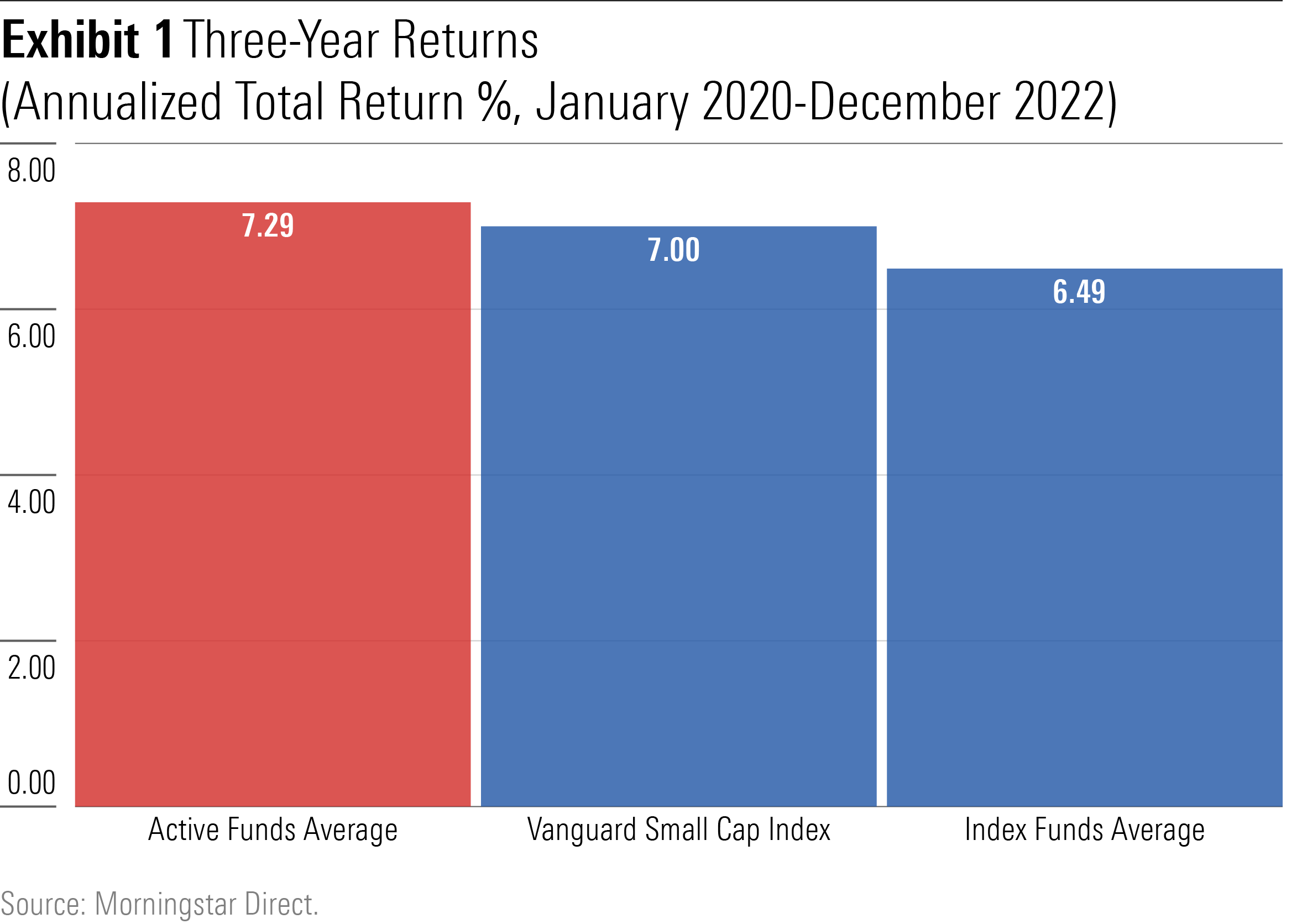

If the size thesis is accurate, then investors in actively run small-company funds have something to celebrate. At least among small-value funds, which I studied in two recent articles, active-fund success no longer attracts new customers. In recent years, active small-value funds have thrived. Yes, they trailed growth-stock funds during the 2020-21 bull market, but they made up ground last year. Over the trailing three years, the active-fund average beat both the index-fund average and the category’s largest fund, bellwether Vanguard Small Cap Value Index.

(Note: The above figures include exchange-traded funds as well as mutual funds.)

Active funds’ victory would be somewhat hollow if they had assumed higher risk along the way. They did not. While active small-company value funds invest in fewer positions than do their indexed rivals, their median number of holdings is 90—a substantial amount. Overall, their annualized standard deviations have almost exactly matched the index funds’.

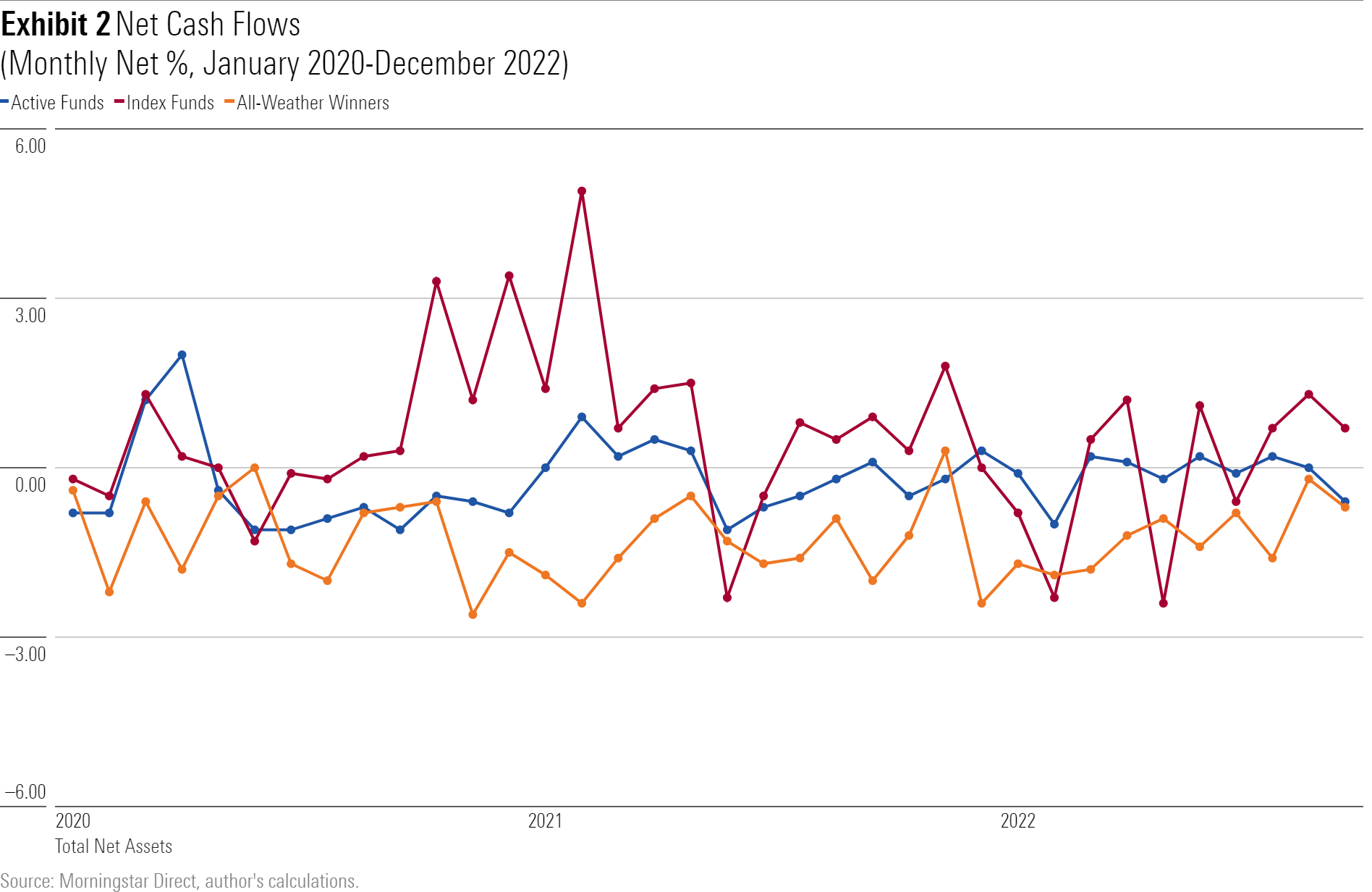

Purchases of active small-value funds have lagged, though. The next chart shows the monthly sales numbers for small-value funds (once again, including ETFs), sorted into three groups: 1) index funds, 2) actively run funds, and 3) the subset of particularly successful five “all-weather funds,” discussed in my Jan. 12 column. Positive figures indicate that the funds enjoyed net inflows from investors for the month, while negative figures represent net redemptions.

The cash flows neatly reverse the order of performance. Drawing the most investor interest were the index funds, which typically received inflows. Following them were all active funds, which had mixed results. At bottom were the all-weather funds, each of which outgained the Morningstar US Market Index (as well as the S&P 500) over the past 21 years, while also holding up far better during the three bear years of 2002, 2008, and 2020. Their reward? Net redemptions.

Summary

I will not overstate the case. Although the evidence suggests that equity funds benefit from maintaining modest asset bases, that conclusion remains contested. Nor has the amount of that alleged boon been established. Therefore, the news that today’s small-value fund winners have not been flooded with new moneys, as were their predecessors, should not be overstated. It is but one positive step.

But for active fund managers, every small advantage counts.

Addendum

After this column was published, a reader admonished me that the math favoring active small-value funds only works within tax-sheltered accounts. He is correct. On an aftertax basis, Vanguard Small Cap Index comfortably outgains the average small-value fund over the trailing three years. My apologies: Although my tax assumption was standard—investment researchers typically discuss returns that are after expenses but before taxes—I should have specified it in this case, because doing so does makes a big difference in the conclusion.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/FGC25JIKZ5EATCXF265D56SZTE.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-25-2024/t_d30270f760794625a1e74b94c0d352af_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DOXM5RLEKJHX5B6OIEWSUMX6X4.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)